Welcome back to the Creative Life Adventure.

I’ve been rewatching the 1984-1989 TV series Miami Vice. Vice was one of my favorite shows at the time, and it holds up better today than I had expected. The series was a brilliant reflection of its age, featuring fashion and music in keeping with the music video style popular at the time, the fatalistic attitude of a generation still living under the threat of nuclear war, and the moralistic titillation so favored by Reaganites, condemning casual sex and drug use by spending an inordinate amount of time dwelling on them.

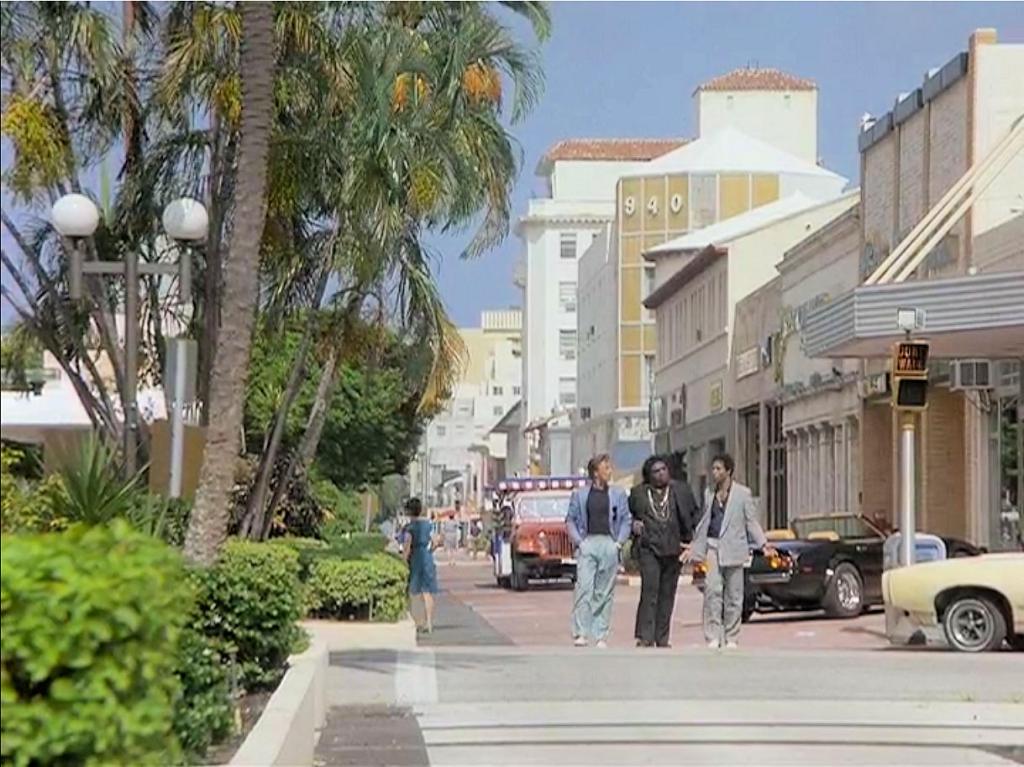

MTV debuted only three years before Vice and quickly immersed itself into, and influenced, popular culture. It may be apocryphal that a two-word memo from NBC executive Brandon Tartikoff – “MTV Cops” – launched the series, but the Music Television network, which really did broadcast music videos in those years, was ubiquitous enough that we all understood Sting’s refrain “I want my MTV” in the 1985 Dire Straits song “Money for Nothing.” The pastel color scheme and synthpop music prominent in the first two seasons fit perfectly with the South Beach vibe of a Miami Beach that was in the early stages of revitalization and gentrification, and the show’s blend of flashiness and moral righteousness offered a unique viewing experience to both the coasts and the flyover states.

The show’s slick cars and expensive fashions fit perfectly with the proud opulence of the Reagans and their wealthiest supporters. President Reagan had just introduced the Strategic Defense Initiative in 1983 as part of his escalation of the Cold War with the Soviet Union. That escalation included 1985’s Reagan Doctrine, a policy of aiding anti-communist movements in Asia, Africa, and Latin America to prevent the rise of, or bring about the fall of, governments allegedly sponsored by the USSR. Miami’s role as a hub between Latin America and the rest of the U.S. made it the perfect setting for a vice squad that frequently investigated the drug and weapons trafficking that were essential components of the Reagan strategy.

Series leads Don Johnson and Philip Michael Thomas might have seemed to come from nowhere, but both had a long list of acting credits prior to their work as Vice detectives James “Sonny” Crockett and Ricardo Tubbs. The show’s additional regulars – Michael Talbott as Stan Switek, John Diehl as Larry Zito, Saundra Santiago as Gina Calabrese, and Olivia Brown as Trudy Joplin – all had perfect chemistry that was completed by the addition of Edward James Olmos as Lieutenant Martin Castillo in the sixth episode, “One Eyed Jack.” The death of a supporting character – Gregory Sierra’s Lt. Lou Rodriguez – in “Calderone’s Return: The Hit List” (S1E4) not only made room for Olmos’ character but gave the weight of reality to the danger the characters faced.

However, the developing bond between Crockett and Tubbs is a big part of what makes the first two seasons so compelling, particularly in “Nobody Lives Forever” (S1E20), “Evan” (S1E21), and “Tale of the Goat” (S2E7). By the season two finale, “Sons and Lovers,” the detectives have a closer rapport with each other than anyone else. Conversely, one of the series’ few significant errors was to gradually orient the show around Crockett as the sole lead character. This is especially evident in “Bushido” (S2E8, brilliantly directed by Edward James Olmos) and “Back in the World” (S2E10). Don Johnson is an underrated actor, but so is Philip Michael Thomas, and Vice worked best as a buddy show with a strong supporting cast. One highlight of the supporting cast, on the other hand, is that even though the series still tends to view women as damsels in distress, at least the women are side by side with the men in confronting crime. “Lombard” (S1E22), “The Prodigal Son” (S2E1), and “Whatever Works” (S2E2) give Gina and Trudy the chance to demonstrate their courage.

Several substantial themes gave the show more depth than one might expect while being entertained by a variety of hot guest stars and rock/pop songs both old and new. The most prominent Vice message was the endless struggle against a culture of tireless evil. Every master criminal killed or arrested was replaced by a new gangster the following week. Arrests were rare, as most villains either died in a shootout at episode’s end or escaped. Tubbs acknowledges this in the season two finale “Sons and Lovers,” identifying Calderone (Miguel Piñero), a cartel leader who haunted the Vice team throughout the first two seasons, as the only major “big one” they managed to do away with.

This relentless struggle impacts the show’s depiction of duty, the allure of power, and lost love. Law enforcement personnel are not inherently noble, as witnessed by the numerous corrupt cops in episdoes like “Heart of Darkness” (S1E2) and “Whatever Works” (S2E2). Nobility is not conferred by a gun or a badge, it is earned through service and sacrifice. Crockett and Tubbs demonstrate this by repeatedly risking their lives and careers to help others, as they do in “One Eyed Jack” (S1E7) and “The Fix” (S2E18). Crockett and Tubbs never stop believing in the possibility of redemption, going out of their way to give the wayward a second chance, as in “Milk Run” (S1E12) and “Little Miss Dangerous” (S2E15). In “Give a Little, Take a Little” (S1E11), Crockett goes so far as to go to prison to avoid publicly naming an informant. The pilot episode’s title, “Brother’s Keeper,” is well taken, as Crockett and Tubbs consistently look out for those who are promised protection within, and sometimes beyond, the legal system.

The detectives’ commitment to duty means that family and friends will often be caught in the crossfire, demonstrated most notably by the death of Tubbs’ brother in the series pilot “Brother’s Keeper” and the near-murder of Crockett’s son and (soon-to-be-ex-)wife in “Calderone’s Return: The Hit List” (S1E4). Even the villains, with an entirely different kind of commitment, pass on their bad karma to family members, in “Little Prince” (S1E11), “The Fix” (S2E18), “Sons and Lovers” (S2E22), and a surprising number of additional episodes. One end result of this is a nearly monastic existence that leaves the Vice detectives with no real opportunity for long-term personal relationships. Time and again, Crockett and Tubbs enter romantic relationships, only to be betrayed – “No Exit” (S1E7) and “The Prodigal Son” (S2E1) – or to see their love meet a deadly end – “Yankee Dollar” (S2E13) and “French Twist” (S2E17).

While Miami Vice deals primarily with personal and local dramas, we are often reminded of the national and global context. Loose gun policies, which we know have only become worse over time, put too many weapons in the hands of civilians, demonstrated in “Nobody Lives Forever” (S1E20) and “Evan” (S1E21). The drug trade that takes up so much of the Vice detectives’ time is not a local issue but a global network: the season two premiere “The Prodigal Son,” perhaps the series’ stylistic peak, gives us the most comprehensive overview of the drug industry, from Columbia to Miami to New York City, with Wall Street at the top of the pyramid. In “Back in the World” (S2E10), we see a nation still in the early stages of decline, a process begun with Vietnam and Watergate, and Crockett acknowledges the Greed Decade by calling “selling out” the new American dream.

In this larger context, one of the show’s most frequent targets is corruption in the Federal government, which during those years meant the Reagan Administration. (Republicans also controlled the U.S. Senate during most of the 1980s, while Democrats controlled the House of Representatives.) As a consequence of the Reagan doctrine, the U.S. exported violence and instability to Latin America, protected drug traffickers, and decimated domestic social services that drove more troubled individuals into dangerous behavior and, ultimately, prison. Throughout the series, the Vice squad faces interference from the CIA, the DEA, and various other Federal representatives while cleaning up the consequences on the streets of Miami. We see arms trafficking in “No Exit” (S1E8) and “Evan” (S1E21), corrupt DEA agents in “The Prodigal Son” (S2E1) and “Sons and Lovers” (S2E22), forced revelation of an informant by a Federal agent in “Definitely Miami” (S2E12) (in this episode, Crockett even says he would have trusted the government only ten years earlier), and the CIA’s role in drug smuggling in “Back in the World” (S2E10).

Ultimately, however, Miami Vice is about individuals who live courageously and carry the weight of a nation’s sins on their shoulders. In “Definitely Miami” (S2E12) and “Payback” (S2E19), we see Crockett experiencing genuine identity conflicts, an emotional state that will progress through seasons three and four as Crockett sinks too deep into his long-time cover as Sonny Burnett. Tubbs finds and loses a son, Gina is sexually assaulted, and Castillo is threatened by rogue CIA operatives. While most of the show’s press focused on a talented array of guest stars – Jimmy Smits, Dennis Farina, Bruce Willis, Pam Grier, and Frank Zappa, among many others, appeared in the first two seasons – and a long list of pop/rock songs to supplement Jan Hammer’s outstanding instrumental scores – the Rolling Stones, Tina Turner, The Police, Dire Straits, Roger Daltrey, even Philip Michael Thomas were among the numerous music contributors – Miami Vice went considerably deeper than an MTV video. Miami Vice made full use of television’s audiovisual potential to present archetypes that incorporated elements of westerns, police procedurals, the myth of urban decay, and contemporary fears of the 1980s, confronting nihilism while never fully losing hope. And while the series became both darker and sillier in seasons three and four, these first two seasons issued forth a television landmark offering escapist entertainment for those who wanted it, and, for those willing to go farther, a telling commentary on the struggle between good and evil in the American landscape of the 1980s.

3 thoughts on “Our Brother’s Keeper: The Existential Angst of Miami Vice, Seasons 1 and 2”