(Note: If you haven’t read it yet, my introductory post on this Star Trek: The Original Series rewatch is a good place to start.)

Original Air Date: April 6, 1967

Crew Death Count: 0 (but a homeless man accidentally kills himself with a phaser and this really deserves more attention)

Bellybuttons: 0

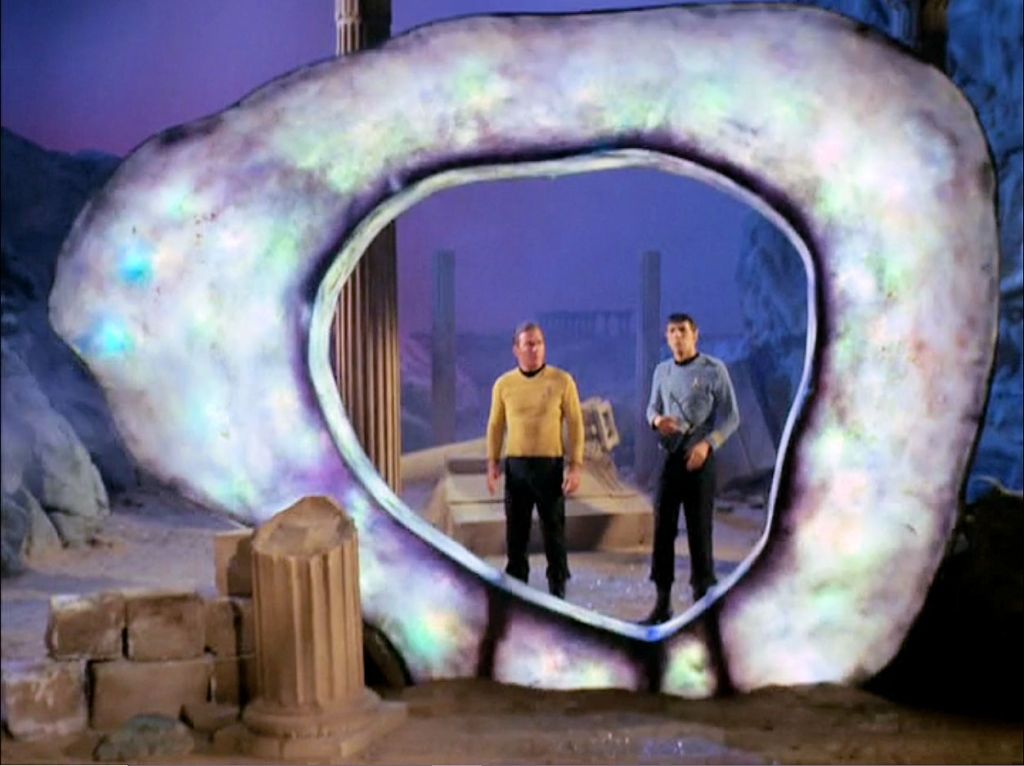

Like “Space Seed,” though for different reasons, “The City On the Edge of Forever” is so weighted with history, it’s difficult to write about objectively. “City” shows up on many lists of the best episodes for the entire Star Trek franchise, and while I’m not one for individual favorites, it remains one of Star Trek‘s finest moments, featuring an outstanding story with acting to match. The episode holds up brilliantly more than fifty years later. The premise is a straightforward time travel conundrum: a mishap on the bridge of the Enterprise causes McCoy to overdose on cordrazine, a powerful stimulant that drives the doctor to a state of extreme paranoia. McCoy flees the ship by beaming down to an unnamed planet, where the sole occupant is the Guardian of Forever, a galactic observer offering a portal to any place at any previous point in time. The delusional McCoy runs through the portal to 1930s New York City (We’re back in 20th century United States! Yay!), where he has altered history in such a way that the Federation will never exist. This is bad news for the landing party in pursuit of McCoy, stranded on the planet with no Enterprise. So Kirk and Spock go through the portal to put things right, which ultimately requires the death of noble pacifist Edith Keeler (Joan Collins), who Kirk has fallen in love with.

“City” is a classic TOS story of sacrifice that illustrates the best qualities of the franchise: an ethical quandary, futuristic elements grounded in terms relatable to contemporary audiences, drama with genuine consequences balanced by a dose of humor, strong acting all around, a perfectly cast guest star, all on a foundation of friendship. There’s even a dose of foreshadowing: Kirk’s instruction to the landing party is that, should he and Spock fail in their mission, each individual is to go through the Guardian’s portal; if they can’t find McCoy, they should get on with their lives as best they can. This is very similar to the premise of the season three episode “All Our Yesterdays.”

Of course, it wouldn’t be Star Trek without flimsy security protocols and weak follow-up, and “City” provides both. The fact that McCoy easily subdues the transporter chief (borrowing some Kirk-Fu moves) and beams to the planet will lead to no improvement in transporter room security in any iteration of Star Trek. Also, there is no investigation of the Guardian of Forever and its extraordinary ability. Yes, the crew, especially Kirk, has a lot to contemplate by the end of the episode. Still, it’s the Guardian of Forever! It tells the landing party it has waited for a question longer than humans have existed. The crew can’t come up with a single follow-up question? What about the civilization that left the ruins surrounding the Guardian, which Spock estimates to be “ten thousand centuries old?” Did they create the Guardian? (The Guardian contradicts itself, first saying, “I am my own beginning,” followed later by, “I was made.”) At the end, the Guardian offers them “many other such journeys.” Imagine the harm that could cause! What if Klingons or Ferrengi show up and accidentally destroy the galaxy? Let’s hope someone thought to release a warning buoy, at the very least.

Nitpicking aside, however, Trek-ish details give “City” considerable depth. Kirk and Spock have a humorous exchange with a police officer who catches them stealing clothes; the scene demonstrates the close rapport between the two men, and lightens the mood without getting into distracting slapstick. Near the end, Kirk, Spock, and McCoy share a brief moment of sheer joy when they are reunited in 1930. And when McCoy arrives in the 1930s, he is distraught over the state of medicine on 20th century earth. He describes it as, “Needles and sutures. All the pain. They used to hand-cut and sew people like garments.” At the time, TOS writers and producers could reasonably have assumed humans were on track to eradicate many illnesses. By the time “City” aired, polio had been virtually eliminated, and the United States licensed a measles vaccine in 1963. A mumps vaccine was in development and would be licensed in late 1967. There was no reason to think this process of conquering diseases wouldn’t continue indefinitely. At the same time, healthcare delivery was improving: the U.S. introduced Medicare and Medicaid in 1965. It must have been difficult, from a 1960s perspective, to imagine how much we would regress in rationing health care according to economic status through unaffordable private insurance and a costly testing-for-profit health care system, not to mention anti-vaccination hysteria, proliferation of snake oil supplements, and a reliance on lifetime “maintenance” prescriptions over genuine treatment. McCoy’s despair is justified, but for the wrong reasons.

Kirk arrives in the 1930s equally concerned with quality of life, but from a socioeconomic standpoint. When Edith Keeler says, “I think that one day they’re going to take all the money that they spend now on war and death-” Kirk is easily able to complete the sentiment: “And make them spend it on life.” When Keeler says to Kirk, “Let me help,” he is pleased to tell her that history will ultimately judge those three words to be even more significant than, “I love you.” Yet love is very much on Kirk’s mind, and his romance with Keeler is easily the most mature and innocent of Kirk’s numerous TOS affairs. He’s not responding to a skimpy outfit, for despite Collins’ considerable beauty she remains modestly attired throughout the episode. Instead, it’s Keeler’s generosity and compassion that attracts Kirk, a reminder that this is the same captain who tried to save his Romulan opponent in “Balance of Terror” and defended the Horta in “The Devil in the Dark.” Unlike past (and future) love interests, Kirk is visibly devastated by her death, burying his face in McCoy’s shoulder when the inevitable occurs – Kirk has never looked so defeated.

Keeler’s message of hope is compelling to Kirk and to us, the viewers, and she is the real star of the episode. Making an avowed pacifist the central character could have been a subtle antiwar message, considering how quickly opposition to the Vietnam War was growing in 1967. The message that Vietnam was the wrong war is reinforced by indicating that World War II was the right one, as Keeler’s 1930s pacifism is declared to be the right sentiment but, as Spock says, “at the wrong time,” in the face of Hitler’s rise to power during that decade (“a rather barbaric period” is how Spock describes it). If Keeler’s message of peace gains too wide an audience, the U.S. will not enter World War II and Nazi Germany will conquer the world with atomic weapons. Given that WW II was less than twenty-five years old at the time, and considering Roddenberry’s war-time service (episode creator Harlan Ellison served in the U.S. Army from 1957 to 1959), the Nazis were an easy and logical choice as villains.

Keeler is a pacifist and probably qualifies as a democratic socialist in the Western European tradition, but the boogeyman of full-on socialism is carefully avoided here. Keeler is happy to risk her own safety to help others: she immediately offers shelter to Kirk and Spock, and later the sick McCoy, fully knowing they may be fugitives from the law. She is equally quick to forgive Kirk and Spock for the theft of a tool set when they commit to returning it. But she expects her charges to work for their keep. She says she won’t support “bums” and assigns Kirk and Spock to work ten hours per day.

Ultimately, fate turns on Spock’s chilling declaration: “Edith Keeler must die.” We can appreciate this clear illustration of “The needs of the many…etc.” and the dramatic conflict faced by Kirk. And yet… and yet… Keeler is essentially a Christ figure who redeems humanity for the sin of a global war. To invert the classic Star Trek mantra, in real life, the sacrifice of the one does not outweigh the sins of the many. The convenient division between Allies and Nazis ignores the inconvenient truth that Hitler only rose to power with the help of the United States and other Allied nations. Chase Manhattan Bank, IBM, Standard Oil, and Coca-Cola were among the many western businesses the Third Reich depended on. (Chase, among others, also collaborated in the seizure of Jewish citizens’ private assets.) The Nazi eugenics practices were based on “theories” devised largely in the United States and the research was partially funded by the likes of the Carnegie Institution, the Rockefeller Foundation, Harvard, and Princeton. Defeating the Nazis was necessary, but only after we helped create our own enemy. We don’t get to take credit for Edith Keeler, she is an outlier in any decade and her death (foreshadowing the real-life death of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., almost one year to the day after “City” first aired) does not absolve us of our sins.

Equally important is the possibility that Keeler didn’t really need to die. Of course, the character’s death is necessary for dramatic effect. Conversation and compromise are never as powerful as death. Consider, though, how open-minded Keeler is. She forecasts atomic energy, space travel, and an end to widespread poverty and illness, confidently predicting “hope and a common future, and those are the days worth living for.” In stating that Keeler must die, Spock forgets his own logic from “The Galileo Seven”: “There are always alternatives.” Keeler also understands that Kirk and Spock have some greater mission than sweeping floors; that conversation is when the “Let me help” line occurs. She even says to Kirk, “You see the same things that I do. We speak the same language.” As outlandish as the Guardian/time travel scenario would have seemed to her, she is practically begging to be brought in on the secret. Kirk and Spock could have tried to reason with Keeler, summarizing the long view of history that would yield to the better future she wishes for. They might even have taken her with them to the 23rd century, where the Federation can clearly use more compassionate but tough-minded ambassadors.

So as inspiring as “The City On the Edge of Forever” is, it doesn’t go far enough. In The Liberation of Paris: How Eisenhower, de Gaulle, and von Choltitz Saved the City of Light, historian Jean Edward Smith describes how General Dwight Eisenhower, Supreme Allied Commander, and General Dietrich von Choltitz, Germany’s military commander in Paris, both essentially defied orders to save Paris at the end of World War II. Eisenhower had orders to delay liberation of the city, and von Choltitz had orders to destroy it should the Allies prevail. Both men understood the futility of those orders and the necessity of Paris as a guiding presence in Europe. In collaboration with Charles de Gaulle, they delayed bombing of strategic sites and accelerated the Allies’ occupation of Paris. Among both Allies and Nazis, many accepted the loss of Paris as inevitable. Destruction is always easy. Instead, Eisenhower and von Choltitz chose the high road and rescued a global city with its centuries of history. No loss of life is acceptable as “the cost of doing business,” and isn’t that really the hopeful future Edith Keeler imagines? Believe it or not, there is a scenario that avoids all unnatural deaths, and if that’s not our ongoing mission, we’re on the wrong course heading. Whether we find light in social workers, cities, or among the stars, we must always set our sights above the horizon, and cling fiercely to the days of hope worth living for.

Next: Operation – Annihilate!