(Note: If you haven’t read it yet, my introductory post on this Star Trek: The Original Series rewatch is a good place to start.)

Original Air Date: November 17, 1967

Crew Death Count: 0 (but the Tellarite ambassador is killed)

Bellybuttons: 1

“Journey to Babel” is a beloved episode for the simple fact of introducing us to Spock’s parents Sarek (Mark Lenard) and Amanda (Jane Wyatt). This took on greater significance when Lenard reprised the role in Star Trek III: The Search for Spock (1983), and Wyatt resumed her role in Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home (1986). The episode deserves credit for that alone, but despite logical shortcomings in the plot, “Journey to Babel” makes for a fascinating (get it?) thought exercise on the classic Star Trek themes of risk and sacrifice.

This week, the Enterprise is assigned to transport more than one hundred diplomats to the planet Babel for a conference that will consider Federation admission for the Coridan system, an important source of dilithium crystals. Among the dignitaries are ambassadors from Andoria, Tellar Prime, and Vulcan, with Vulcan Sarek and human Amanda leading the Vulcan delegation. There is considerable political intrigue regarding alleged illicit mining operations on Coridan and powerful differences of opinion as to whether or not to grant the system Federation membership. The scenario is reminiscent of Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country (1991), when the Enterprise again serves as interstellar escort to a Federation conference regarding a hot-button political topic (and in both cases, the Enterprise is shadowed by a mysterious starship). In “Journey to Babel,” nearly everything goes wrong at once: the Enterprise is attacked by a ship of unknown origin, the Tellarite ambassador is murdered, a member of the Andorian delegation stabs Kirk (giving the Shat an excuse to lounge topless in sickbay), and Sarek suffers from a heart condition that requires life-saving surgery, for which only Spock can serve as a blood donor. Most critics argue that the plot is too contrived, but I appreciate this pressure-cooker scenario that forces our characters to demonstrate their true character by making hard choices.

The episode is even more dependent than most on guest characters; not just Amanda and Sarek, but the Andorian ambassador (Reggie Nalder), the rogue member of the Andorian delegation (William O’Connell), who turns out to be an Orion spy, and the Tellarite ambassador (John Wheeler). They are all outstanding in their roles. While Lenard gets most of the attention as Spock’s father, Jane Wyatt is glorious as Amanda, giving the role the gravitas it deserves but also with the approachability we expect from a committed educator. In addition to the guest stars, Chapel assists in sickbay and Chekov takes over the science station in Spock’s absence, so the entire episode feels fresh just for the constant presence of faces who are new, or feel new because we don’t see them that often. Even the red shirts don’t completely fumble, for once. A disturbing number of security officers form an honor guard to greet the Vulcan delegation; this seems oddly militaristic for a diplomatic function, but maybe the Vulcan embassy is wise to how often the Enterprise is hijacked. Later, two security officers actually subdue a criminal for a change rather than getting knocked unconscious. Security even escorts the Orion agent to the bridge without losing him.

In fact, Sarek’s character is probably the most poorly written, at least through the first act. Despite Lenard perfectly matching Nimoy in Vulcan haughtiness (particularly in their final scene together, when they recover in sickbay), Sarek is initially downright hostile toward Spock, refusing to speak to or even acknowledge his son. He won’t even return Spock’s Vulcan salute. This is Sarek’s clumsy way of expressing disapproval at Spock’s career choice, which we know, thanks to “The Menagerie,” was made more than thirteen years ago. Considering Sarek’s entire career as an ambassador requires him to get along with others, it’s unfathomable that this highly logical individual would carry on a childish grudge over so many years. The writing improves throughout the episode, however, and soon enough Sarek expresses pride in Spock privately to Amanda, even if his dual roles, as a Vulcan and an ambassador, discourage him from demonstrating it publicly. We also get more insight into Spock’s embarrassment over discussing pon farr in “Amok Time”; Sarek is also secretive about matters of health, keeping his heart condition from his own wife until it overwhelms him. And in the final scene, as mentioned, the chemistry between Spock and Sarek is priceless – we genuinely believe they are father and son, even though Lenard was only seven years older than Nimoy.

Jane Wyatt, on the other hand, was just the right age, twenty-one years older than Nimoy. Every time I watch “Journey to Babel,” I appreciate her work here even more. The role of Amanda is perfectly acted and perfectly written. Many people criticize this episode for Sarek’s patronizing attitude toward Amanda, telling her, “Wife. Attend.” when he wants her attention. Despite TOS’ frequent issues with misogyny, in this case the dynamic is appropriate. Sarek is an ambassador and image matters. I believe Amanda would happily appear subservient to Sarek in public if it boosted his diplomatic stature. Their private exchanges are entirely different, however; in those scenes, Amanda proves that she is an equal partner in this marriage.

Amanda also demonstrates considerable insight while yielding to the occasional emotional indulgence of any human mother. She tells McCoy about Spock’s childhood pet, which McCoy receives like juicy gossip despite Spock’s refusal to be embarrassed. She also doesn’t fully understand the demands of her son’s job. When Sarek’s health declines to the point that he needs prompt surgery, and Kirk is unconscious from his own injuries, she urges Spock to relinquish command of the Enterprise, saying, “Any competent officer can command this ship.” Spock rightfully corrects her: “Any competent officer can command this ship under normal circumstances.” We know there is no normal on the Enterprise. And when Amanda notices that Spock still hasn’t learned to smile (I’d pay money to see the Vulcan smile training course), her son demonstrates his own insight into human conduct: “Humans smile with so little provocation.”

The question we’re tempted to ask, of course, is how a human female ever ended up marrying a Vulcan male. Amanda addresses this early on in an insightful exchange with Kirk, deflating the TOS myth of human exceptionalism at the same time: “You don’t understand the Vulcan way, Captain. It’s logical. It’s a better way than ours. But it’s not easy.” Yet when Amanda criticizes Spock for remaining committed to his duty despite the risk to Sarek’s life, Spock elaborates on “the Vulcan way,” as if to reassure her of the soundness of his decision-making as well as hers: “It means to adopt a philosophy, a way of life, which is logical and beneficial. We cannot disregard that philosophy merely for personal gain, no matter how important that gain might be.” Even the Andorian ambassador reinforces the integrity of the Vulcan way, when he tells Spock, “Perhaps you should forget logic and devote yourself to motivations of passion or gain. Those are reasons for murder.” In other words, violent crimes will be extremely rare among any species resistant to passion or material gain. This is consistent with Amanda’s earlier statement: “Vulcans believe that peace should not depend on force.”

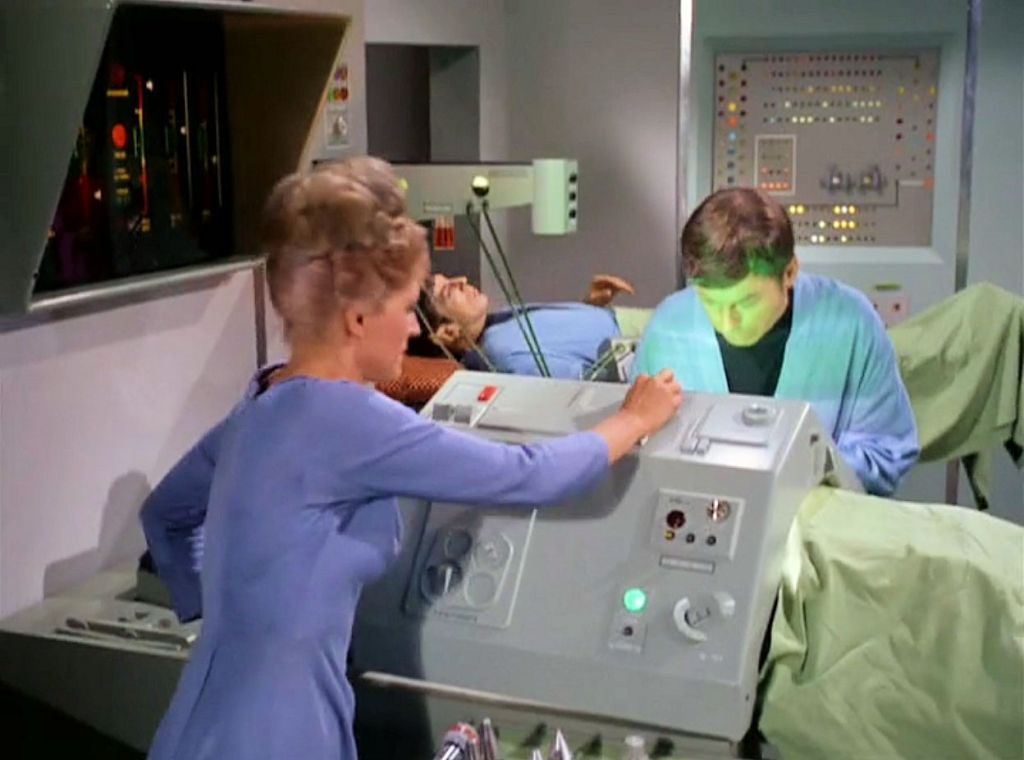

Like Sarek, McCoy gets off to a shaky start. He’s in full-time complainer mode over the dress uniform he’s required to wear (“Feel like my neck’s in a sling.”) and all these VIPs on the Enterprise cramping his style. When Sarek’s heart condition is initially disclosed, McCoy claims almost complete ignorance of Vulcan physiology – why would he attempt surgery under such conditions, and why doesn’t Spock, who should be at least as knowledgeable of Vulcan physiology as he is of 20th century American history, offer advice? But McCoy and Chapel both shine during the actual surgery. They never lose their cool while the Enterprise is rocked by enemy fire and both patients are in mortal danger. The doctor, like Spock, will make his own ethical calculations: an experimental drug will allow Spock to function as a blood donor for Sarek, but if it fails both patients will die. McCoy opposes the surgery, preferring to lose one patient rather than two, but yields when Spock reminds him that Sarek, at the moment, is more important to the Federation. And in the episode’s final scene, McCoy reminds all of his patients (three now, with Kirk recovering from his stab wound) that sickbay is his domain. Shushing their banter, he appears to look straight at the camera, the first time we’ve been directly acknowledged as observers on this journey, telling us, “Well, what do you know? I finally got the last word.”

Kirk and McCoy face significant ethical dilemmas, but the real burden is on Spock. Being pulled in two directions at once – whether to risk his life to save his father, or risk Sarek’s life by fully committing to his duties after Kirk’s injury – symbolizes the dual nature of Spock’s entire life. Amanda reflects on this during that earlier conversation with Kirk. She hasn’t forgotten the long-ago teasing Spock endured from Vulcan children, who apparently are every bit as cruel as human children. Judging from Spock’s pained expressions, he hasn’t forgotten, either. Amanda claims Starfleet is the only place her son is truly at home. In a way, Spock’s Starfleet responsibilities align perfectly with his description of “the Vulcan way,” where the needs of the many outweigh the needs of the few. Spock decides not to compromise his duties, risking his father’s life, something he points out Sarek himself would approve of. The real balance Spock needs to weigh is Sarek’s significance as an ambassador who will play a major role in the Coridan decision and its later impact on the Federation. Ultimately, Spock is nudged along when Kirk makes his own sacrifice, pretending to be recovered enough to resume command, enticing Spock into the personal, human, decision of providing the necessary transfusion for his father.

For much of the episode, I wondered why the diplomats were so hostile toward each other. Negotiation is their job, after all. Then I recalled accounts of heated United Nations conferences and conduct of various countries’ ambassadorial staffs during turbulent moments in history. While we might expect ambassadors to be the most compromising representatives of their species, these undignified dignitaries haven’t forgotten that their job isn’t really to compromise, but to debate, argue, and arm-wrestle their way into compromising as little as possible on behalf of their people. (Just watch this exchange between U.S. Ambassador to the UN Adlai Stevenson and Soviet Ambassador Valerian Zorin during the Cuban Missile Crisis. Thankfully, there are no poisonings or stabbings. This exchange is also the inspiration for Christopher Plummer‘s dramatic demand, “Don’t wait for the translation!” in Star Trek VI.) The site of the conference, Babel, warns us we’re in for a difficult undertaking. In the Old Testament Book of Genesis, humans spoke one language until they conspired to build the Tower of Babel. Whether their goal was to stay dry on higher ground (because the Great Flood earlier in Genesis didn’t work out so well for them) or to seek equal status with their creator, God did not look kindly on the project; he scattered groups of humans around the world, giving them different languages, putting an end to collective, god-like aspirations.

Dean Acheson knew a thing or two about political calculations and the challenges of negotiating diverse languages and cultures. As an Assistant Secretary of State (1944-1945), Under Secretary of State (1945-1947), and U.S. Secretary of State (1949-1953), Acheson played significant roles in the Marshall Plan, the formation of NATO, and America’s overall Cold War foreign policy. When Acheson resigned as Under Secretary of State in the summer of 1947, not expecting to return to government service, he received a personal note of thanks from President Truman that said, in part, “May you live long and prosper…” While the traditional Vulcan farewell, introduced in “Amok Time,” does not appear in “Journey to Babel,” we can easily imagine it between the lines. The Vulcan salute, also from “Amok Time,” carries even more weight in these days of subterfuge. Tellarites want Coridan excluded from the Federation so they can exploit the inhabitants for their dilithium. Sarek wants Coridan admitted to the Federation to protect them from such abuse. And the Orions – the real culprits in the crimes to disrupt the conference – want their own opportunity to take advantage of Coridan. The journey to Babel is more than a bureaucratic escapade, it’s a larger undertaking, to undo what God hath wrought in a fit of anger, thereby creating unity of purpose among disparate peoples. As Sarek brings together Coridan and the Federation, including the Tellarites and Andorians, Amanda brings together her own family. The Coridan conference is secure, and Spock and Sarek are on speaking terms again. As much as this validates “the Vulcan way,” both successes might never have been without the human wife and mother working behind the scenes. We can debate the wisdom of logic versus emotion, but the key players all took risks determined by logical priorities. When Amanda expresses frustration with the stubbornness of her son and husband in the final scene, Sarek says he married her because, “At the time, it seemed the logical thing to do.” Sarek’s dignity may prevent him from voicing it, but he is every bit as grateful for this decision as we are.

Next: Friday’s Child