(Note: If you haven’t read it yet, my introductory post on this Star Trek: The Original Series rewatch is a good place to start.)

Original Air Date: February 2, 1967

Crew Death Count: 0 (a fake death is the episode’s central conflict)

Bellybuttons: 0 (but Kirk’s uniform is damaged in yet another fistfight)

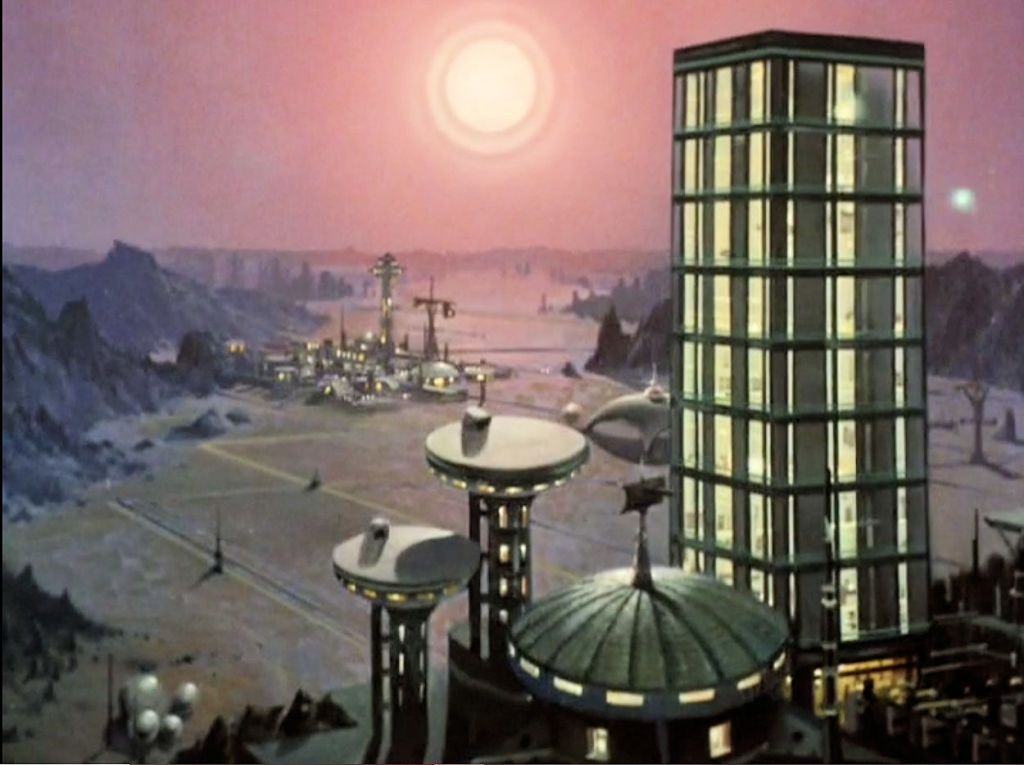

“Court Martial” returns us to Starbase 11, where Spock hijacked the Enterprise at the beginning of “The Menagerie.” This time, the Enterprise has suffered damage during an ion storm that led to the death of the ship’s records officer Ben Finney (Richard Webb), a former friend of Kirk who blames the captain for an incident years ago that kept Finney off the command career path. The Enterprise logs don’t match Kirk’s testimony, making him suspect in Finney’s death. Somehow it never occurs to anyone that the records might have been altered by the records officer who hates the captain. Hence, the need for a court martial to get us to the truth.

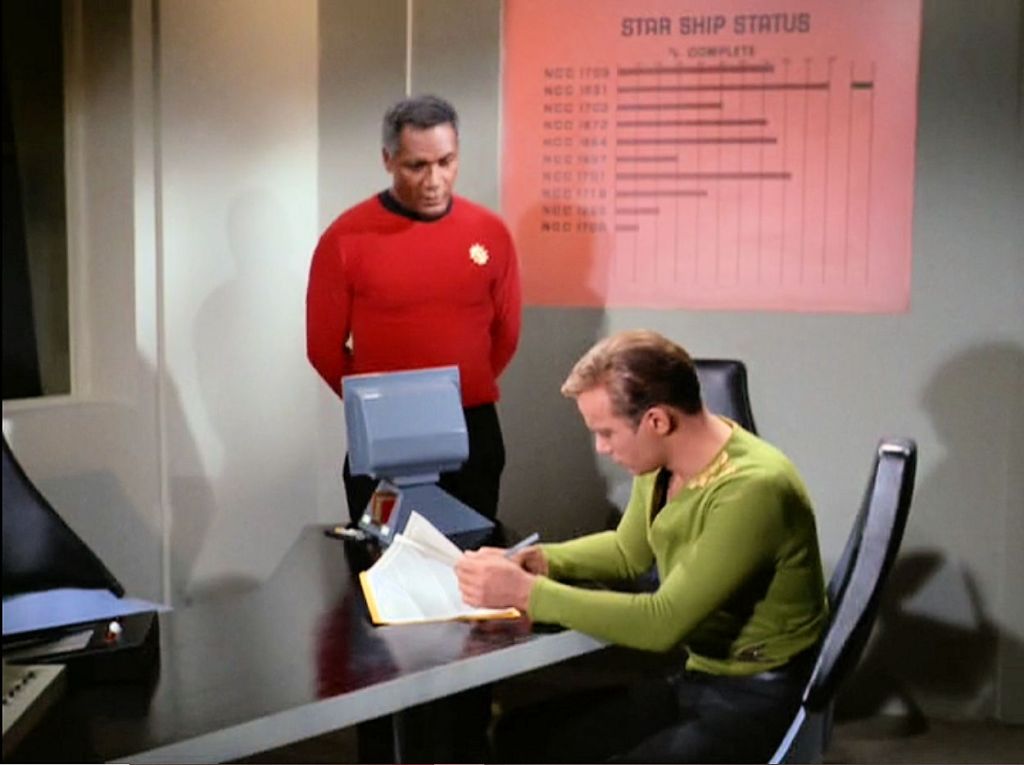

“Court Martial” features some delightful IDIC (Infinite Diversity in Infinite Combinations) casting, presenting diversity as status quo rather than calling our attention to it. Starbase 11 is commanded by Commodore Stone (the Afro-Portuguese Percy Rodriguez). Stone rose through the ranks not as a bureaucrat, but a starship captain, so he has first-hand understanding of Kirk’s experience. Despite his early doubts about Kirk, he goes to great lengths to keep the court martial fair, insisting on hearing Finney’s final “confession” despite the Enterprise having entered a decaying orbit that risks the safety of Stone and his colleagues. In addition, Kirk’s legal nemesis is the prosecuting attorney Lieutenant Shaw (Joan Marshall), not a teeny-bopper, coffee-serving yeoman, but an adult, intelligent woman (Marshall was the same age as Shatner). The Enterprise personnel officer is an Asian woman (played by Nancy Wong), and Uhura gets another turn at the helm in the episode’s final moments.

Another interesting detail is the Starfleet paperwork that sets off the initial conflict. The Federation is a bureaucracy, and the death of a crew member will require documentation as to cause and circumstances. We can trust that similar follow-up has occurred with past deaths of crew members. (This is not the first time Starfleet protocols have given Kirk a headache, as McCoy demonstrated in “Dagger of the Mind.”) The drama that unfolds, resolving the divergence between Kirk’s official statement and the ship’s logs, demonstrates that Starfleet understands the importance of preserving a record of the truth, and we will return to this subject later.

However, there is “truth” to human behavior. Our personalities remain fundamentally consistent – unless affected by excessive circumstances, good people remain good and liars remain liars. Spock understands this; that’s why he never doubts Kirk’s innocence. “Human beings have characteristics,” he says, “just as inanimate objects do.” Commodore Stone should have understood this, and his immediate accusation of someone with Kirk’s history defies logic. The anger of Finney’s daughter, Jamey (named after Kirk, demonstrating the bond that existed between the two men), is much easier to understand. Her initial shock at her father’s death prompts her to blame Kirk, easily convinced that her father’s hatred was reciprocated by the captain. Her complete change of opinion by episode’s end, ready to defend Kirk, demonstrates the unreliability of emotions and the necessity of a justice system based on law and facts over opinions or stereotypes.

Nevertheless, the machinations of the justice system have implications outside the courts. While awaiting his court martial, Kirk and McCoy enter a social establishment, where Kirk gets the cold shoulder from other Starfleet officers. Kirk’s reputation is already damaged, with or without a conviction. How often do dramatic headlines name suspects whose lives will never be the same, even if they are proven innocent? In the U.S. in 2012-2016, only about 13% of robbery arrests led to a felony conviction. We can only speculate about the damage done to the lives of those who were wrongfully accused or arrested. In fact, public accusation and the associated damage to one’s reputation may be the point. Before he restores order with a fair court martial, Commodore Stone seems a little too eager to blame Finney’s death on a captain who has, allegedly, reached a point of “physical breakdown, possibly even mental collapse.” Even prosecutor Shaw’s instructions are Machiavellian: “I have to do my very best to have you slapped down hard.” Sabotaging someone’s entire career may cause considerably more damage than anything a prosecutor can accomplish in the courtroom.

Two of this week’s guest characters, Shaw and Kirk’s defense attorney Samuel T. Cogley (Elisha Cook, Jr.), provide food for thought but contribute little to the plot. We soon learn that Shaw is another of Kirk’s former love interests. This personal history is not only unnecessary, but weakens Shaw as an antagonist. We never believe she’s fully committed to her job, because her job is to convict Kirk. A more effective adversary would have been someone on record as disliking Kirk. Cogley, meanwhile, gives some passionate talk about man vs. machine, a stand-in for our own conscience and fears in both the 1960s and today. But Cogley fails at his one job: he loses his case! Kirk is nearly pronounced guilty until Spock shows up with the results of his research into the Enterprise computer system. (In fairness, Cogley is the first to speculate that Finney might still be alive.) Cogley also loses credibility by citing the likes of Moses and the Bible as among his trusted foundations for legal theory. Half of the Ten Commandments as delivered by Moses relate to God’s obsessive need to be worshiped, and the Bible (assuming he refers to the Christian Bible of Old and New Testaments, which is problematic enough in co-opting Jewish scriptures) is rife with contradictions and includes such punitive options as torture, assault, and murder.

We can at least compliment Cogley for his love of books. We assume Kirk is a reader, because we’ve seen books in his quarters and we know he enjoys Shakespeare. Yet we doubt Kirk’s attachment to his small collection when he tells Cogley a computer takes up less space than physical books. The episode ends with Cogley gifting a book, title unknown, to Kirk via Shaw. Is this what launches the “fondness for antiques” that prompts Spock to observe Kirk’s birthday with a gift of Dickens’ A Tale of Two Cities in Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan (1982)?

The “life first” message of “Court Martial” is obvious, but as with all parables of humans pushed aside by machines, technology isn’t the real villain. Our enemy, as always, is ourselves. The problem has a dual nature, the first being our faith in technology. As an engineer by training and a science-fiction fan at heart, it pains me to acknowledge that our reliance on technology is often misplaced. We see this in “Court Martial” when Starfleet is ready to abandon one of its finest based on a sabotaged computer record. Despite Cogley’s claim that the Enterprise computer is the most damning witness against Kirk, the real culprit is Finney, who altered the computer records. This event feeds into the second failure of human nature: our use of technology. As we know from the old garbage-in-garbage-out premise, our technology can only do what we tell it to do. In the 1960s, this fear had a more overtly sinister nature that generally manifested itself through nuclear weapons, hostile robots, and out of control computer systems. In the early 21st century, the danger is more subtle but perhaps equally frightening: job-killing automation, 24/7 surveillance (which we often invite into our own homes) and Minority Report-style attempts at crime prediction are already causing more harm than good. The problem isn’t the technology, but the weaknesses and biases of both the creators and users of these systems. The argument becomes circular and always comes back to us: anyone who develops such devices should never doubt that they will eventually fall in to the wrong hands. Robert Browning may have believed that “a man’s reach should exceed his grasp,” but history has shown that our reach always exceeds our character. Progress is not the ability to do something, but the wisdom to distinguish between what we should or should not do.

Despite the anti-computer rhetoric in “Court Martial,” the most memorable moments are those between our flesh-and-blood characters. Spock‘s testimony is the most powerful of all because, as with his defense of Kirk in “The Enemy Within,” he is the least likely to base statements on emotional bias. As he has several times in the past, Spock turns to 3D chess for insight, finding that he can consistently defeat the computer in a game for which he himself programmed it. McCoy, on the other hand, is less than stellar, failing his captain by bumbling through a testimony for which he is clearly unprepared. Worse, he becomes downright irrational when he doubts Spock’s intentions with the 3D chess exercise, calling Spock “the most cold-blooded man I’ve ever known.” And Finney is so clearly unstable that, like Bailey (“The Corbomite Maneuver”) and Stiles (“Balance of Terror”), his mere presence on the Enterprise is a mystery. He calls to mind modern-day conspiracy theorists and right-wing fanatics unable to face the impersonal nature of the real world, finding someone to blame for every perceived slight. The Finney we meet in the final act is a homicidal lunatic who has to be subdued by Kirk-Fu and institutionalized; it’s hard to believe he became that way overnight. Meanwhile, Kirk, not for the first time, demonstrates why he is the captain. He is understandably angry, but remains an optimist, trusting that the very system that has turned on him will correct itself and, ultimately, proclaim his innocence. Kirk waives the right to request alternate jurors in the court martial if he feels the current ones are biased, even though Shaw’s marching orders make it clear they are biased. But like the technology that depends on human nature, Kirk’s faith is not really in the system, but in his colleagues’ efforts to keep that system’s standards high.

One question is not answered at the end of “Court Martial,” but we trust the answer is affirmative: can the altered ship’s record be restored so that it reflects actual events? The ease of modifying the Enterprise database is apparently never addressed, as it remains a problem twenty-four years later, in Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country (1991). Our more immediate concern is that the truth is documented so that Kirk’s reputation is truly restored. More importantly, especially in our age of “alternative facts” and normalized lies, we understand that truth is not a philosophical construct, but something we must work to understand and maintain. Facts exist: something either happened or it didn’t. Kirk is either right or wrong; there is no middle ground. The overzealous Stone has a visible change in attitude when he hears the facts of Kirk’s service record recited. Jamey, Finney’s daughter, has a change of heart after learning the facts of Kirk’s history with her father when she reads their past correspondence. Decisions can only be made once the facts, or probabilities when considering future events, are established. The forces of darkness, represented here by Finney and, to a lesser extent, an establishment not designed to account for a lone nut, will always try to subvert the truth. Evil never gets tired. The burden is on the rest of us to guard against these forces and confront them whenever they rise up. The truth is a vital tool in achieving one of the public’s greatest duties: to rally around the good guys when they’re threatened. Even if we don’t need them today, one day we will.