(Note: If you haven’t read it yet, my introductory post on this Star Trek: The Original Series rewatch is a good place to start.)

Original Air Date: March 29, 1968

Crew Death Count: 0

Bellybuttons: 0

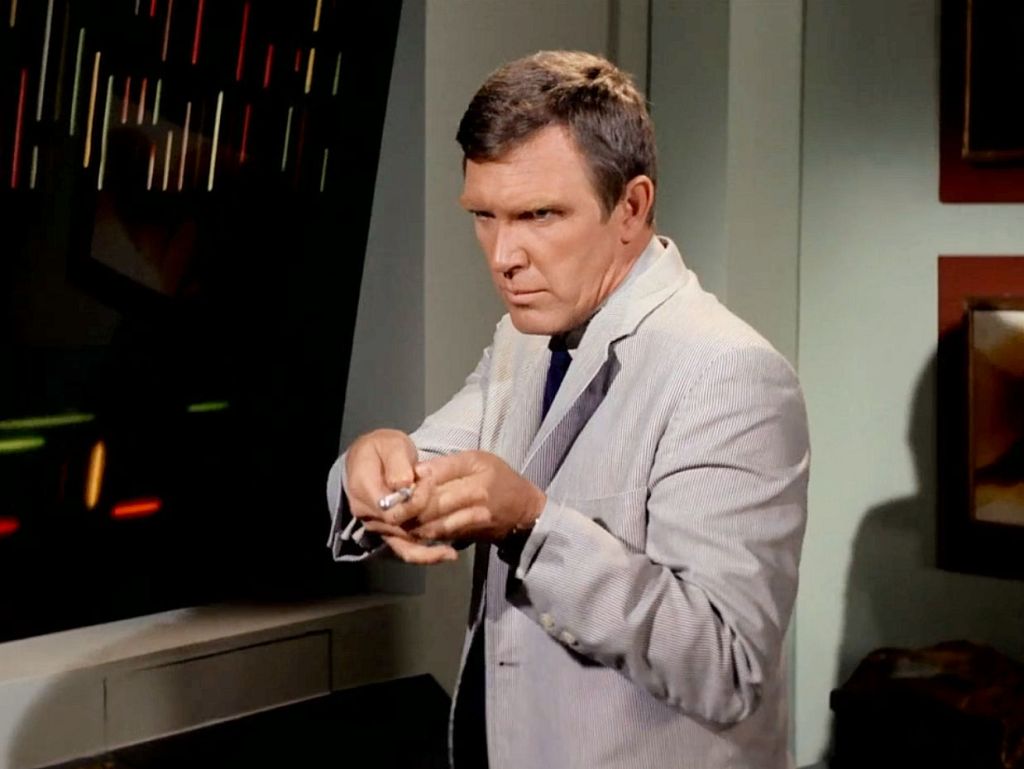

“Assignment: Earth” is a powerful reminder of the lack of continuity of most 1960s TV series, when shows were presented more like anthologies with consistent characters and a reset button that could be pressed each week. In some ways, the episode barely qualifies as Star Trek, yet it fits perfectly in the Trek philosophy. This week, the Enterprise has traveled back in time to….oh, no, again?…20th century earth. The crew accidentally encounters Gary Seven (Robert Lansing), an earthling who has been trained by someone somewhere to intervene whenever humans are in serious trouble. His current task is to sabotage a nuclear missile launch without causing actual harm, frightening the global powers into getting along better. Seven is a good guy, but our usual good guys get in his way and become the bad guys. Until they become good guys in the end by getting out of the way of the real good guy.

It’s no secret that “Assignment: Earth” was originally written as the pilot for a half-hour stand-alone series. When no one bought the series, Gene Roddenberry reworked it as a TOS episode, hoping to create a spin-off series featuring Gary Seven and his ditzy sidekick Roberta Lincoln (Teri Garr). It seems unlikely that would have happened, though Lansing’s portrayal of Seven is brilliant. Even if NBC had gone forward with the series, Teri Garr was reportedly so upset by the experience that she has generally refused to discuss it since.

We do get a few nods to previous episodes but they’re not essential to the plot. The Enterprise travels back in time with the same slingshot method as “Tomorrow is Yesterday.” That episode, however, gave us a plausible reason for the Enterprise to appear in the past, and the crew demonstrated appropriate concern about corrupting the timeline with their presence. In “Assignment: Earth,” the crew has gone back to 1968 – how convenient! – on a research excursion to better understand how humans of the era (really, Americans) managed to survive potentially catastrophic times. It’s a complete diversion from the crew’s true mission of exploration and creates terrible risks. The mission simply makes no sense and the complete lack of logic undermines the entire episode. Remove the spaceship and “Assignment: Earth” feels more like Mission: Impossible (1966-1973) meets Quantum Leap (1989-1993). Also, Seven compares the current earth situation – on the verge of nuclear war – to that of Omicron IV. Is this in the same system as Omicron Ceti III from “This Side of Paradise”?

Gary Seven’s origins and abilities are appropriately vague. He carries a magic pen that performs whatever function is needed at any given moment, including leaving individuals as stupefied as McCoy’s horse tranquilizers. He is somehow impervious to the Vulcan nerve pinch. He can mimic other voices. And Seven talks about aliens from a distant world taking people from earth as far back as six thousand years ago. The Landru computer in “The Return of the Archons” was six thousand years old, and Apollo and company visited earth five thousand years ago (“Who Mourns for Adonais?”). Are they all related somehow? Could the mysterious recruiters be the Old Ones? Whoever they are, they appear to have undertaken the noble mission of rescuing societies on the verge of self-destruction. “A truly advanced planet wouldn’t use force,” Seven says. “They wouldn’t come here in strange alien forms. The best of all possible methods would be to take human beings to their world, train them for generations until they’re needed here.” In fact, Seven’s original mission is to determine the whereabouts of two similar agents already assigned to earth. In their absence, manipulating the nuclear rocket becomes Seven’s responsibility. The episode’s most poignant moment comes when Seven learns his colleagues were killed in a car crash. Seven demonstrates the mournfulness we’d like to see more often from Kirk. “That just doesn’t make sense,” Seven says, “for them to die in something as useless as an automobile accident.”

Lincoln is written as a stereotypical dumb blond and contributes nothing useful to the story. Even more inexplicable is Isis, the black cat Seven carries everywhere he goes. Isis meows or claws someone at a couple of key moments, otherwise she is generally in the way. (She does subdue an Enterprise security officer, but that’s hardly surprising.) During the brief time Seven is captive on the Enterprise, Spock develops an odd fascination with Isis, saying, “I find myself strangely drawn to it.” This is a complete turn-around from his description of cats as “ruthless” and “terrifying” in “Catspaw.” Spock’s reaction becomes a little creepy at the end of the episode, when Isis briefly assumes human form (April Tatro). Human Isis has no dialogue and quickly reverts back to feline form, leaving her, like Lincoln, almost entirely submissive to Seven throughout the episode.

“Assignment: Earth” drags considerably in the third act, when Seven spends an inordinate amount of time tinkering with the nuclear missile (which, in long shots, is really footage of an Apollo rocket). Mr. Scott does some fine surveillance work, but it’s all for naught because it only serves Kirk’s and Spock’s obstructionist actions. In the final act, Kirk is forced to choose whether to trust Seven, hoping he will detonate the out of control nuclear warhead at precisely the right moment (which, in reality, is NEVER), or stop Seven and hope Spock can detonate it before it hits earth. Spock, of all people, decides Kirk needs to use “human intuition” given the lack of facts with which to make a logical decision. Seven convinces Kirk that they are on the same side and detonates the missile at a high enough altitude to terrify the people of earth without causing immediate damage. (Sorry about that radioactive fallout, folks!) Later, Spock reports that the incident “resulted in a new and stronger international agreement against the use of such weapons.” In fact, in January, 1967, both the U.S. and USSR had signed the Outer Space Treaty, which, among other things, banned the placement of nuclear weapons in space. The episode’s anti-nukes message is well taken, but heavy-handed and muddled in the midst of magic pens and shape-changing cats.

One fascinating moment occurs early in the episode, when Spock describes the significant moment at which they have arrived, an unspecified day in 1968: “There will be an important assassination today, an equally dangerous government coup in Asia, and – this could be highly critical – the launching of an orbital nuclear warhead platform by the United States countering a similar launch by other powers.” On April 4, six days after “Assignment: Earth” aired, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., was assassinated in Memphis, Tennessee, and the unmanned Apollo 6 rocket, thankfully lacking nuclear weapons, was launched from the Kennedy Space Center in Florida. The continent is wrong, but the short-lived Sergeants’ Coup in Sierra Leone began on April 18, one of a series of coups in that country during the late 1960s. Our crew doesn’t see much action in this episode – “I’ve never felt so helpless,” Kirk says – but they do perform the worthwhile task of observing. Sadly, one of the most important questions raised by “Assignment: Earth,” how these events will be reported in the ship’s logs for further study, perhaps even to try to contact the distant watchers, is never addressed.

Our crew’s passivity is the primary reason “Assignment: Earth” doesn’t hold up, but it’s also the key takeaway from the episode. The Enterprise crew’s main function here is to interfere with Gary Seven’s important work, only to back away and try to support his effort in the end. Perhaps that is what Kirk needs to learn. A former employer of mine liked to remind his staff that sometimes doing nothing is the best option. Learning when to take action versus when to sit still – choosing our battles, in other words – is one of life’s more challenging lessons. Seven, in this scenario, is clearly better qualified than Kirk – he has more sophisticated technology at his disposal and is more familiar with the situation at hand. “Earth technology and science has progressed faster than political and social knowledge,” Seven says. This is the same reason vigilantes are a bad idea, why public health matters should be settled by experienced health care professionals, and why trained educators should establish school curriculum. Sometimes the smartest thing to do is get out of the way and let the experts do their jobs.

Next: Spock’s Brain