(Note: If you haven’t read it yet, my introductory post on this Star Trek: The Original Series rewatch is a good place to start.)

Original Air Date: January 19, 1968

Crew Death Count: 0 (all four hundred members of the Intrepid’s crew are killed, as are the “billions” of inhabitants of the Gamma 7A star system)

Bellybuttons: 0

“The Immunity Syndrome” somewhat parallels “The Doomsday Machine,” with a dose of “Operation – Annihilate!” and Star Trek: The Motion Picture (1979) thrown in. This week, an Enterprise crew exhausted from saving the galaxy is en route to shore leave when they are diverted to investigate strange goings-on in the Gamma 7A star system. The Vulcan ship Intrepid, with a crew of four hundred, is exploring Gamma 7A until it is destroyed, which we learn about long distance when Spock reacts to it like Ben Kenobi reacting to the destruction of Alderaan. The Enterprise arrives to find the entire system and its “billions of inhabitants” consumed by a massive, single-celled organism similar to a virus. The Enterprise is pulled into the organism’s zone and the crew must think fast or face the same fate as the Intrepid.

The crew is visibly tired when the episode begins and they become more frazzled as the entity siphons off their energy – watch Scott, Chapel, and McCoy sweating by the episode’s mid-point, or Kirk snapping at his officers when they struggle to find answers. McCoy revives the increasingly “nervous, weak, and irritable” crew with undefined stimulants, then quickly regrets the decision because of the harmful consequences of long-term stimulant use. McCoy also struggles early on, when he examines Spock after the first officer’s intense reaction to the Intrepid’s destruction. The doctor determines Spock to be fit, “If I can trust these crazy Vulcan readings.” Spock has been with the crew long enough, and the planet Vulcan isn’t difficult to contact – shouldn’t McCoy have better information on Vulcan physiology by now?

One highlight of “The Immunity Syndrome” is that it fully acknowledges Vulcan superiority. Spock is affected by the Intrepid’s demise far beyond a shocked expression at the science station. He refers to the Intrepid’s crew throughout the episode, partially to compare their strategy to that of the Enterprise, and partially to acknowledge the loss of so many fellow Vulcans. It also gives Spock a chance to put McCoy in his place after all those half-breed comments. He tells the doctor, “You find it easier to understand the death of one than the death of a million. You speak about the objective hardness of the Vulcan heart, yet how little room there seems to be in yours.” This is reminiscent of the statement by German journalist Kurt Tucholsky in 1925, “The death of one man: that is a catastrophe. One hundred thousand deaths: that is a statistic!” (Soviet leader Joseph Stalin is often credited with this line, but Tucholsky appears to have said it first.) When McCoy protests with, “Suffer the death of thy neighbor, eh, Spock? Now, you wouldn’t wish that on us, would you?” Spock replies, “It might have rendered your history a bit less bloody.” At that, understanding he has no argument, McCoy keeps silent. Finally, given the choice between McCoy or Spock to conduct a shuttlecraft exploration of the entity, Kirk is forced to admit that Spock’s physical and emotional endurance make him the obvious choice.

At some point, Kirk takes his ship past the point of no return, choosing to attempt to kill the organism rather than flee. This is a debatable decision, considering how little information they have on the entity and the possibility that their odds might improve if they joined with other starships. Still, Kirk reminds his crew, “Our mission is to investigate,” and the threat of the creature reproducing is too great. The organism’s behavior is never fully explained, and I think this is an episode where a little mystery adds to the tension of the story. For example, how does the entity feed on both biological and mechanical energy? As Spock describes it, “We seem to have entered a zone of energy which is incompatible with our living and mechanical processes. As we draw closer to the source, it grows stronger and we grow weaker.” The only real WTF moment is when McCoy tells Kirk, “According to the life monitors, we’re dying.” Huh? What are “life monitors”? And why is there only one entity? It seems odd that it would suddenly appear fully-formed. This continues the pattern from “The Man Trap” and “Metamorphosis” of one surviving representative of an entire species.

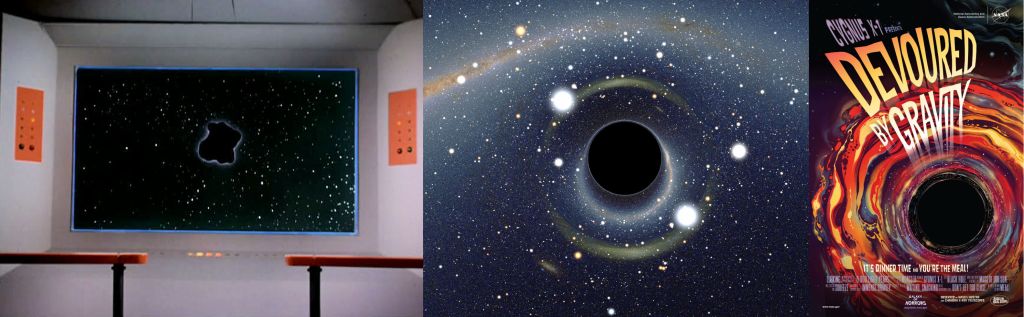

The organism comes across as a living version of “The Doomsday Machine,” destroying everything in its path as it moves through space. The Enterprise crew compares it to a biological pathogen. “I would speculate that this unknown life form is invading our galaxy like a virus,” Spock says. Because the entity is surrounded by a vast region of starless space, the analogy of a black hole kept coming to mind. Black holes are much better understood today than they were in the 1960s, but in 1964 an intense interstellar x-ray source was observed called Cygnus X-1. It was suspected of being a black hole, but not confidently identified as such until 1990. (Rush even recorded a song about Cygnus X-1 for their 1977 album A Farewell to Kings.) NASA attempted to identify additional such x-ray sources with the Uhuru Satellite, launched in 1970.

“The Immunity Syndrome” invites comparison to other Star Trek voyages, with the mindless (we think) expansionary destruction of the alien collective in “Operation – Annihilate!” or Spock’s solo examination of a vast, threatening entity in Star Trek: The Motion Picture. Still, the episode does have a couple of mis-characterizations. For example, why does McCoy suddenly become a shameless opportunist when he lobbies to pilot the exploratory shuttlecraft? Forgetting that he recommended fleeing (“I recommend survival.”) only a short time before, he calls the organism, “the greatest living laboratory…” He is downright exuberant when talking about the learning opportunity as if in denial of the mission’s expected ending. The scene of Kirk agonizing over which of his friends to send to his death is genuinely touching, yet when Spock is presumed dead, both he and McCoy barely react. Finally, it wouldn’t be TOS without a little misogyny: Kirk begins and ends the episode ogling a yeoman as he anticipates his pending shore leave.

NCC-1701: Actual dialogue from the episode:

- Kirk: “…one giant forward thrust.”

- McCoy: “…go slow when we penetrated its vulnerable spots.”

- Kirk: “When do you estimate penetration?”

- Spock: “The area of penetration will no doubt be sensitive.”

- Spock: “…relatively insensitive to interior irritation.”

- Kirk: “We’ll implant it and back away.”

- McCoy: “It’s still plenty sensitive.”

Ultimately, the winning strategy feels like a non-strategy. Using an antimatter bomb to blow up the creature, rescuing Spock as they zoom away from the pending destruction, makes for an unsatisfying conclusion. Can’t antimatter always be used to counteract matter? In real life, the energy resulting from matter-antimatter reactions is speculated to have numerous potential applications. But we’re dealing with the Star Trek world, where, according to Memory Alpha, “Depending on the type of antimatter in use it can interact with, modify, or destroy normal matter.” This puts us in dangerous territory with the prospect of invalidating the crew’s past creativity: could they have used antimatter to dispel all of their prior enemies? Best, perhaps, not to think about it.

Kirk, except for the sexism, remains the fearless leader and the intermediary between head and heart, but “The Immunity Syndrome” is really about Spock and McCoy. For all their bickering, both agree on the futility of coexistence with the organism – imagine trying to initiate a dialogue with a single virus. Previous episodes have offered hints, but finally we see the true complexity of the Spock/McCoy relationship. Each man, raised to believe in the superiority of his respective species, sees in the other a colleague and prospective friend who shatters an entire cultural mythology. The fear resulting from that crumbling foundation drives McCoy and Spock to constantly snipe at each other while their experience in the forge of frontier exploration forces each to admire and appreciate the other. Of course McCoy wishes Spock luck on his exploratory mission, but pride drives him to express it privately. Of course McCoy’s emotional outbursts cause Spock discomfort, but he respects the physician’s compassion and is wise enough to play along, offering his “Captain McCoy” response to the doctor’s exuberant, “Shut up, Spock, we’re rescuing you!” The lifelong bro-mance between Kirk and Spock has always been essential to Star Trek, but the dynamic between Spock and McCoy is more challenging and, in some ways, stronger as a result. No surprise then that McCoy will be the one defending Spock in Star Trek: The Motion Picture and that Spock, even if fate had offered him a choice, could have trusted no one but McCoy with his very soul in Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan (1982).

Fellowship is an ongoing theme in Star Trek and “The Immunity Syndrome” demonstrates the stark contrast between the camaraderie of Spock and McCoy versus the virus-like entity, alone in its empty region of space. Unlike the heartbreaking loneliness of the salt vampire from “The Man Trap,” or the Companion from “Metamorphosis,” or even Kirk himself (“I’ve always known that when I die, I’ll die alone.”), Spock and McCoy will hold one another accountable while watching each other’s backs when the chips are down. In The Last Black Man in San Francisco (2019), lifelong San Franciscan Jimmy Fails overhears newcomers criticizing his city. “You don’t get to hate it unless you love it,” he tells them. The love-hate dynamic between Spock and McCoy allows both to constantly raise the bar of achievement while releasing the inevitable tension of rebuilding their worldviews. McCoy and Spock will live or die together, keeping each other on their toes every step of the way. It may be exasperating, but they’ll both be better men for the experience.

Next: A Private Little War