(Note: If you haven’t read it yet, my introductory post on this Star Trek: The Original Series rewatch is a good place to start.)

Original Air Date: February 9, 1968

Crew Death Count: 0 (But Sargon, Thalassa, and Henoch all go to that great receptacle in the sky)

Bellybuttons: 0

After the lunacy of “A Private Little War,” this week we return to genuine science-fiction, with a thought-provoking story, a memorable guest star, and a clever revisiting of several of TOS’ recurring themes. In response to a distress call, the Enterprise travels, according to Spock, “hundreds of light years past where any earth ship has ever explored.” (What about Vulcan or Andorian ships?) Deep under the surface of an otherwise lifeless planet, the crew finds three disembodied individuals in large, glowing spheres, receptacles where they have waited half a million years for someone to arrive and help them. The three matter-entities, Sargon (voiced by James Doohan), Henoch, and Thalassa, want to build android bodies to inhabit so they can rejoin the living. They need to borrow existing bodies to conduct the work, and they’ve chosen Kirk, Spock, and astro-biologist Dr. Ann Mulhall (Diana Muldaur). There are two complications, however. One is that alien possession puts the human bodies into life-threatening metabolic overdrive, so that “metabolic reduction” injections are necessary to keep them alive. The second is that Henoch isn’t so wild about the android plan; he prefers to keep Spock’s body, and Henoch is the one preparing the metabolic reduction formula.

Diana Muldaur is perfect in the role of Mulhall/Thalassa and, like Dr. M’Benga in “A Private Little War,” it’s a shame she couldn’t have become a recurring character. This is the first of three roles Muldaur played between TOS and TNG, all of them doctors. Mulhall is no coffee-serving yeoman. She is treated as an equal member of the crew who forms her own opinions and speaks her mind, even interrupting McCoy at one point. When Kirk seeks opinions from his officers about whether or not to proceed with the body-swapping, Mulhall remains true to her profession, voting to go forward because “I’m a scientist.” According to Greek mythology, Thalassa was not only the goddess of the sea, but the physical embodiment of the Mediterranean Ocean. The sea can be calm and inviting one day, turbulent the next, just as Thalassa in “Return to Tomorrow” is torn between the good/evil alternatives offered by Sargon and Henoch. Thalassa’s middle role in the cosmic trio makes her more passive, but Mulhall is the kind of strong female character TOS could have used more of. I fully agree with those who are disappointed that one of the show’s established female characters (Uhura or Chapel) wasn’t chosen for Thalassa’s stand-in, but Muldaur is great either way.

Sargon is Thalassa’s husband, because of course all ancient, hyper-intelligent species will adhere to the same male/female pair bonding common to 1960s America. Sargon makes his considerable mental powers obvious early on, communicating telepathically and controlling who does or does not join the landing party. We don’t fully understand Sargon’s claims, namely that if he perishes, “all of mankind” will follow. But it’s Sargon who explains the relevant history: “One day our minds became so powerful, we dared think of ourselves as gods.” Waging god-like war, this society that is never named destroyed itself and their planet’s atmosphere, leaving only a few survivors who were able to transfer their minds to the receptacles. In a fairly useless add-on, Sargon addresses the landing party as “my children,” because his ancestors went forth to populate the galaxy and may have been earth’s Adam and Eve. (Which makes it odd that those early earthlings could have been so easily influenced by Apollo and company from “Who Mourns for Adonais?”)

Like the Organians in “Errand of Mercy,” Sargon is one of the few TOS characters to resist the corrupting influence of power. Realizing that his Freaky Friday ambition will sound preposterous or threatening, he initially takes charge of Kirk’s body without permission. The experience does exactly what Sargon hoped – confirm his sincere intentions to Kirk. Beyond that, Sargon refuses to proceed by force, giving the landing party the freedom to choose. It doesn’t hurt that Sargon offers the temptation of his species’ advanced medical and engineering technology, a reversal of the Prime Directive that promises Scott, who will help build the androids, warp engines the size of a walnut. Sargon’s refusal to take from others simply because he can is reminiscent of the “Mirror, Mirror” prologue, when Kirk offered the same choice when requesting dilithium from the pacifist Halkans. We can imagine that Sargon wasn’t always so noble, considering that he must have been one of the instigators of the war that destroyed his planet. Perhaps he was a conqueror like Sargon the Great, ruler of the Akkadian Empire during the 24th and 23rd centuries BC, and possibly the first human to control an entire empire. Sargon the Great inspired Mesopotamian monarchs for centuries, while the Sargon of “Return to Tomorrow” wants to share his hard-earned lessons: “We can move among the people who do live, teaching them, helping them not to make the errors we did.”

Sargon reports that “Only the best minds were chosen to survive,” among his people. Who selected those best minds, and how, may explain the presence of Sargon’s nemesis Henoch. It’s safe to assume Henoch was among the ruling class. If I were a leader at such a time, I would certainly declare myself one of the “best minds” and essential to survival of the species. Perhaps Henoch was able to do the same. Henoch never commits to living in an android body; like Sylvia in “Catspaw,” Henoch is seduced by the sensual pleasures of physical life. Awaking in Spock’s body, he responds immediately to Chapel in a way Spock’s ascetic lifestyle would never permit: “You are a lovely female,” Henoch says. “A pleasant sight to wake up to after half a million years.” He ridicules the sterility of the android bodies under construction, unfeeling automatons that are little more than mobile versions of the receptacles that held their minds. (No one seems to remember the advanced android technology devised by Roger Korby in “What Are Little Girls Made Of?”) Unlike Sargon, Henoch is perfectly willing to use his powers toward his corrupt ends, preparing a toxic version of the metabolic reduction formula for Kirk/Sargon and hypnotizing Chapel into forgetfulness when she notices the swap. Like Thalassa and Sargon, Henoch’s name is wisely chosen: Biblical Henoch (more commonly Enoch) was a grandson of Adam and did not die of natural causes but was taken by God while still alive, perhaps because of the apocalyptic visions God was said to have shared with Henoch. Likewise, Sargon outwits Henoch and casts him from the living, returning Spock’s body to its rightful owner.

“Return to Tomorrow” spends a lot of time in sickbay, and McCoy and Chapel are vital to the story. For once, McCoy’s complaining serves a useful purpose. When McCoy initially questions the wisdom of transporting 112 miles below the planet’s surface, we can’t help but think of McCoy’s similar reaction to beaming into Regula I in Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan (1982). The doctor’s primary concern is always for his patients, and he opposes the mind/body transfer from the start, calling it “rather indecent.” He monitors Kirk, Mulhall, and Spock constantly while they are possessed, and he frequently urges retreat to avoid driving their metabolic states too far. When Thalassa offers him a deal – she’ll keep Mulhall’s body and save Kirk, whose body is now lifeless after receiving the false injections – McCoy gives the only appropriate response: “I will not peddle flesh.” Chapel ends up being something of a pawn, but, in the end, a completely willing pawn. The final subterfuge, when Sargon and Thalassa hide Spock’s mind in Chapel’s body, deserves more exploration. Chapel’s unrequited love for Spock is no secret; now the two are bonded more intimately than any conventional romance would allow. Spock, in particular, is bound to be effected by this, but the moment passes too quickly. (This scene also sidesteps a confusing plot point: if both Spock’s consciousness and Chapel’s can occupy Chapel’s body at the same time, why did Kirk, Spock, and Mulhall have to vacate their bodies for Sargon, Henoch, and Thalassa?)

The episode is primarily a study of two classic TOS themes: balance of power and risk. Sargon, Thalassa, and Henoch dramatize the continuum from compassionate autocrat to sociopath. Thalassa, in the middle, yields briefly to temptation, declaring a desire to keep Mulhall’s body and threatening McCoy in the process. “I could destroy you with a single thought,” she says. But, like Dr. Dehner in “Where No Man Has Gone Before,” she comes to her senses long enough to join Sargon in defeating the power-hungry Henoch. Yet even Sargon has too much power for one individual, a fact he acknowledges in the end. The point is emphasized when Kirk mirrors Sargon’s offer of choice to those he could otherwise command: “I’m in command, I could order this,” he tells his officers when discussing the body-swap. “But I’m not.” Like the Talosians who refuse to share the secrets of their mental abilities for fear other cultures will become corrupted (“The Menagerie“), Sargon and Thalassa both accept that the allure of power will always prove too great, and so they reject the android bodies and allow their minds to dissipate.

The fact that Sargon, Thalassa, and Henoch are all that remains of their people reminds us that resisting power isn’t just essential for individuals, but societies. The Bulletin of Atomic Scientists, founded by biophysicist Eugene Rabinowitch and physicist Hyman Goldsmith, created the Doomsday Clock in 1947 to easily visualize humanity’s proximity to self-destruction. While the Doomsday Clock has been set primarily according to the risk of nuclear war, in 2007 human-caused climate change was added to the equation. In 1963, primarily in response to a nuclear test ban treaty between the U.S. and Soviet Union, the clock was set back to twelve minutes to midnight. But in 1968, the year “Return to Tomorrow” aired, the clock was moved forward to seven minutes to midnight, as a result of expanded proliferation of nuclear weapons and America’s aggression in Vietnam. We don’t know the specifics of how Sargon’s people killed themselves, but nuclear war, the most fearsome power yet devised by humans, must have been on the minds of the writers at the time.

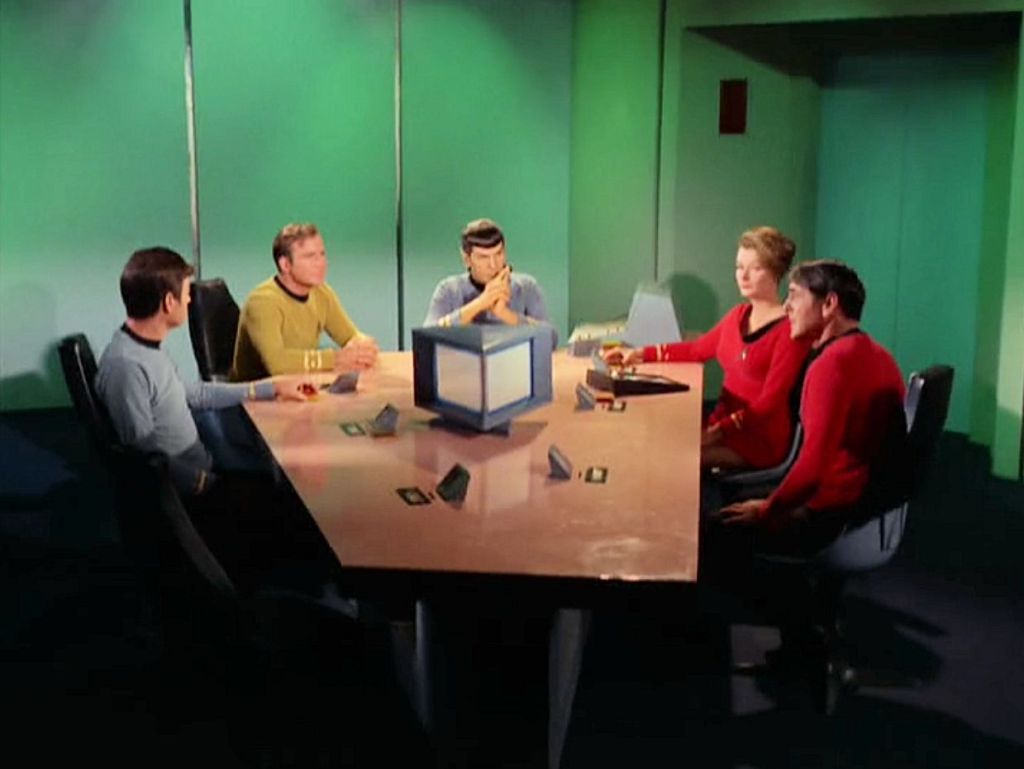

Kirk, who has no patience for fist-thumping sovereigns, seems inspired by Sargon’s good intentions. While he was nearly repulsed by the idea of sentient androids in “What Are Little Girls Made Of?”, here Kirk has a different perspective because he has literally looked inside Sargon’s mind. (“I know him now. I know what he is and what he wants.”) Sargon also scores points by recognizing good looks when he sees them: “Your captain has an excellent body, Dr. McCoy,” Sargon says the first time he occupies Kirk. “I compliment you both on the condition in which you maintained it.” Kirk is so moved by his encounter with Sargon, he demonstrates his collective decision-making style in the kind of briefing room scene more common in season one. While confirming for his officers that participation is voluntary, Kirk rouses them to action: “Do you wish that the first Apollo mission hadn’t reached the moon?” (The first successful manned Apollo mission was Apollo 7 in October, 1968. The crew of Apollo 11 reached the lunar surface in July, 1969.) “Risk is our business,” he reminds the crew. “That’s what this starship is all about. That’s why we’re aboard her.”

Kirk’s dazzling physique aside, TOS has repeatedly warned against the danger of a life lived strictly of the mind. We’ve seen this expressed from different angles in “What Are Little Girls Made Of?”, “The Menagerie,” and “Metamorphosis,” among others. Gene Roddenberry clearly appreciated physical movement and sensation, not as a means of satisfying health insurance companies or arbitrary BMI benchmarks, but as a fundamental aspect of the human experience. Henoch reminds Thalassa repeatedly of how lacking android bodies will be compared to living flesh. Thalassa finally breaks down and rejects the robotic body: “I cannot live in that thing.” She embraces Sargon and asks, “Can two minds press together like this?” The prospect of a future in unfeeling bodies, their compassion thankfully preventing them from stealing human bodies, is another reason Thalassa and Sargon yield to oblivion in the end. The scenario is reminiscent of the Singularity, the human/technology unification projected by scientific notables like Ray Kurzweil. The Singularity predicts that developments in genetics, nanotechnology, and robotics will lead to a dramatic extension in human lifespan. Crucial to the Singularity is the synergistic combination of all three fields, not progress in only one or the other. This is one implausible feature of the alien receptacles: it’s hard to imagine the development of such radical brain storage technology without similar advances in other disciplines that would have made android bodies possible at the same time.

Sargon calls his society’s fall from godhood the “ultimate crisis” all species must face. In reality, we have created one crisis after another for ourselves – climate change, proliferation of weapons (nuclear or otherwise), an embrace of magical thinking over scientific principles, systemic racial and gender discrimination – and it’s hard not to be depressed at humanity’s overall trend. “Return to Tomorrow” offers a happy ending for the Enterprise crew, but what are we to make of the three aliens lost to time, the final representatives of a highly advanced society that traveled the stars centuries before the Federation? Is there no reset option, no opportunity to back away from the false progress of ability without imagination? What choices did Sargon’s people make when they were so close to the end? Will Kirk and his crew understand and share the gospel of awareness? Will we? In 2020, the Doomsday Clock was moved forward to only one hundred seconds from midnight. We should measure our days carefully, because on the grand scale of history, we may only have seconds to turn back the clock.

Next: Patterns of Force