I love Billy.

Willem Dafoe on William Friedkin, Friedkin Uncut (2018)

Last week I mentioned a re-watch of Woody Allen‘s Manhattan (1979). (If you’re reading this, I assume you’re familiar with the movie – to avoid spoilers, skip down to the flower pictures.) Clearly, Manhattan‘s premise of Allen’s Isaac Davis dating teenager Tracy (Mariel Hemingway) is disturbing. (Not nearly as disturbing as Allen’s real-life experiences that inspired the screenplay. Yikes!) But it’s perhaps less disturbing if you view Isaac, not as the film’s protagonist, but the villain. In the past, I assumed that in a movie co-written and directed by Allen, he would intend his character to be the hero. But the female characters, Tracy, Mary (Diane Keaton), and Jill (Meryl Streep) are all much smarter and more mature than Isaac or his philandering friend Yale (MIchael Murphy). (The exception to this masculine insecurity appears to be Wallace Shawn‘s Jeremiah, clearly a more advanced Isaac-doppelgänger.) This interpretation falls apart a bit when Mary becomes unhinged in the final act, but even that’s a direct result of the men-folks’ flaky behavior. Either way, Isaac is clearly the bad guy. Allen acknowledges this throughout the film, admitting the impropriety of dating a teenager and positioning Isaac, in one scene, in his proper out-dated evolutionary place next to a gorilla skeleton. Like all good villains, Isaac lives by a quasi-moral code, refusing to get involved with Mary while she’s having an affair with Yale, despite Yale being married to someone else. Like all sexual predators, Isaac is terrified of his actions becoming public, in this case in ex-wife Jill’s tell-all memoir. And listen to him repeatedly tell Tracy, “Don’t be so mature,” as if emotional maturity will cause him to melt like splashing water on the Wicked Witch. Finally, look at that sinister expression he delivers straight to the camera in the last scene with Tracy. All of these choices are deliberate.

Is this my attempt to rationalize guilt-free enjoyment of a problematic movie because of its stellar cinematography (Gordon Willis! Black and white!), settings (the Hayden Planetarium! the Guggenheim!), and music (Gershwin! the New York Philharmonic!)? Probably a little. But Roger Ebert was a lot smarter than me and he agreed. Revisiting Manhattan in 2001, Ebert described Isaac as “a man whose yearnings and insecurities are founded on a deep immaturity.” And while Ebert describes Manhattan as a story of loss, I would argue the film has a happy ending: Tracy frees herself from Isaac’s clutches and goes to London.

If none of this is convincing, just stick with When Harry Met Sally… (1989), Nora Ephron’s and Rob Reiner’s corrective to Manhattan, featuring a male protagonist who comes to his senses and demonstrates genuine growth by movie’s end. Both movies conclude with the man dashing through city streets to find the woman he loves (or thinks he loves) – Harry tells Sally how wonderful she is, while Isaac talks only about what he wants.

We planted a couple of scorpion-tails in our front yard two summers ago. They were nearly wiped out last fall by Hurricane Ian and a period of drought earlier this year, but have recovered nicely this summer. The small blossoms are lovely but they’re especially fun to watch because tons of butterflies and buzzy flying critters love them. The individual plants are somewhat short-lived, but they self-seed easily (not so much as to be invasive), so two plants have turned into two small groves of scorpion-tails.

I also read The Sound of Things Falling by Juan Gabriel Vásquez this week. The novel is a fascinating exploration of how our lives can be affected by the most unlikely people and events, and about how our own life choices can affect others in unintended ways. This is the second novel by Vásquez I’ve read and I liked them both very much.

- P. 70: “…what was driving me was neither sentiment nor emotion, but the intuition we sometimes have that some events have shaped our lives more than they should or appear to have.”

- P. 221: “Adulthood brings with it the pernicious illusion of control, and perhaps even depends on it. I mean that mirage of dominion over our own life that allows us to feel like adults, for we associate maturity with autonomy, the sovereign right to determine what is going to happen to us next. Disillusion comes sooner or later, but it always comes, it doesn’t miss an appointment, it never has. When it arrives we receive it without too much surprise, for no one who lives long enough can be surprised to find their biography has been molded by distant events, by other people’s wills, with little or no participation from our own decisions.”

- P. 264: “So far in my life no one has been able to explain convincingly, beyond banal historical causes, why a country [Columbia] should choose as its capital its most remote and hidden city [Bogotá]. It’s not our fault that we Bogotanos are stuffy and cold and distant, because that’s what our city is like, and you can’t blame us for greeting strangers warily, for we’re not used to them.”

Meanwhile, I’m continuing my slow read of Lewis Mumford’s The City in History. Mumford’s tome is Euro-centric, because that’s the region he was most familiar with, but he acknowledged that in the Introduction.

- P. 345: “Between the fifteenth and the eighteenth century, a new complex of cultural traits took shape in Europe. Both the form and the contents of urban life were, in consequence, radically altered. The new pattern of existence sprang out of a new economy, that of mercantilist capitalism; a new political framework, mainly that of a centralized despotism or oligarchy, usually embodied in a national state; and a new ideological form, that derived from mechanistic physics, whose underlying postulates had been laid down, long before, in the army and the monastery.”

- P. 346: “But the very shock of the Black Death also produced a quite different reaction: a tremendous concentration of energies, not on death, eternity, security, stability, but on all that human audacity might seize and master within the limits of a single lifetime. Overnight, six of the seven deadly sins turned into cardinal virtues; and the worst sin of all, the sin of pride, became the mark of the new leaders of society, alike in the counting house and on the battlefield. To produce and display wealth, to seize and extend power, became the universal imperatives: they had long been practiced, but they were now openly avowed, as guiding principles for a whole society.”

- P. 351: “The concept of the baroque, as it shaped itself in the seventeenth century, is particularly useful because it holds in itself the two contradictory elements of the age. First, the abstract mathematical and methodical side, expressed to perfection in its rigorous street plans, its formal city layouts, and in its geometrically ordered gardens and landscape designs. And at the same time, in the painting and sculpture of the period, it embraces the sensuous, rebellious, extravagant, anti-classical, anti-mechanical side, expressed in its clothes and its sexual life and its religious fanaticism, and its crazy statecraft. Between the sixteenth and the nineteenth century, these two elements existed together: sometimes acting separately, sometimes held in tension within a larger whole.”

- P. 365: “From the sixteenth century on the domestic clock was widespread in upper-class households. But whereas baroque space invited movement, travel, conquest by speed – witness the early sail-wagons and velocipedes and the later promenades aériennes [aerial walks] or chute-the-chutes – baroque time lacked dimensions: it was a moment-to-moment continuum. Time no longer expressed itself as cumulative and continuous (durée), but as quanta of seconds and minutes: it ceased to be life-time. The social mode of baroque time is fashion, which changes every year; and in the world of fashion a new sin was invented – that of being out of date. Its practical instrument was the newspaper, which deals with scattered, logically incoherent ‘events’ from day to day: no underlying connection except contemporaneity.”

- P. 377: “Unfortunately, the very distractions of the court became duties. The ‘performance of leisure’ imposed new sacrifices. The dinner party, the ball, the formal visit, as worked out by the aristocracy and by those who, after the seventeenth century, aped them, gave satisfaction only to those for whom form is more important than content. To be ‘seen,’ to be ‘recognized,’ to be ‘accepted’ were the supreme social duties, indeed the work of a whole lifetime. In its final dismal vulgarization, in reports in contemporary gossip columns, this is the part still performed in night clubs and theatrical openings.”

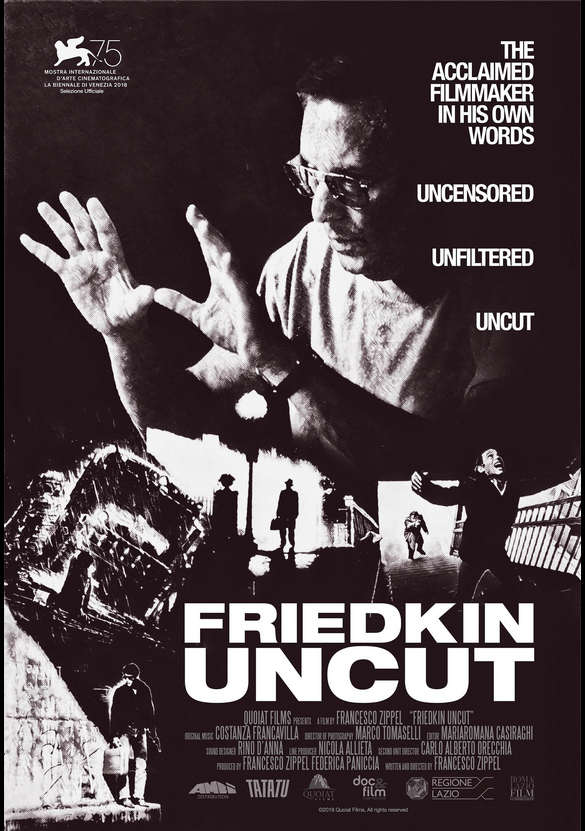

Finally, if you’re as sad as I am over the death of William Friedkin this week, consider watching (or revisiting) Sorcerer (1977), for the hair-raising bridge sequence if nothing else. Then watch the documentary Friedkin Uncut (2018), which is currently streaming on Tubi. And maybe give a listen to the Friedkin tribute from The Movies That Made Me podcast.

Leave a comment