If once the sterile dreams and sadistic nightmares that obsess the ruling elite are banished, there will be such a release of human vitality as will make the Renascence seem almost a stillbirth.

Lewis Mumford, The City in History, p. 574

Last week I wrote about David Thomson‘s 2012 book The Big Screen: The Story of the Movies. I continue reading it and it’s a mesmerizing book. Of course, art is subjective, so I disagree with him occasionally – while I admire Hitchcock, I’m among the few who don’t regard Vertigo (1958) as a classic, yet I love Rope (1948), which Thomson considers “clumsy” and “portentous.” Either way, Thomson does an outstanding job of telling the history of cinema within a greater social and political context. And he doesn’t shy away from the possible negative outcomes of immersing ourselves too often in fictional stories and characters, particularly with the rise of television in the 1950s.

- P. 110: “The atmosphere and values of a certain kind of movie story and its publicity have seeped into American culture as a whole, along with the overall hope that stories might be true. There is a moment common to two John Ford pictures – Fort Apache (1948) and The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962) – at which characters surveying the ‘history’ of the west say, ‘When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.’ Some Ford enthusiasts rejoice in that despairing attitude and may have come to terms with an America in which people know and trust less and less. Suppose the legend says there are weapons of mass destruction in Iraq? It is a dangerous resignation, and it may sustain deplorable educational standards in the land of the free.”

- P. 111: “As the Depression set in, it was clear that the studios were making their money from increasingly impoverished people by selling them a dream of infinite success and remote happiness. They could tell the world and themselves that the movies preached the gospel that anyone could make it in America, and [Louis B.] Mayer was generous with uplifting stories of his own journey. But that message was akin to the promotion that would come out of the Las Vegas casinos twenty years and more later: anyone can win. Exactly right, but only with the corollary that nearly everyone will lose. Except the house.”

- P. 207: “We have lived long enough to see that the vaunted heroics of the war movie can be a disguise for our political ignorance and helplessness.”

- P. 229: “‘Noir’ today may be the best known and most honored of American movie genres, and you can make a case for it as the most culturally influential. But in the era when the best noir films were being made, the word would have meant nothing in America except an affected way of ordering your coffee. Noir enters American English consciousness only from French writing on film, above all in the book by Raymond Borde and Étienne Chaumeton, Panorama du Film Noir Américain, 1941-1953, published in 1955 (but not translated into English until 2002). It is one of the first examples of French eyes recognizing truths in American film, a search in which America itself was negligent for decades.”

- P. 243: Quoting David O. Selznick in 1951: “Hollywood’s like Egypt. Full of crumbled pyramids. It’ll never come back. It’ll just keep crumbling until finally the wind blows the last studio prop across the sands.”

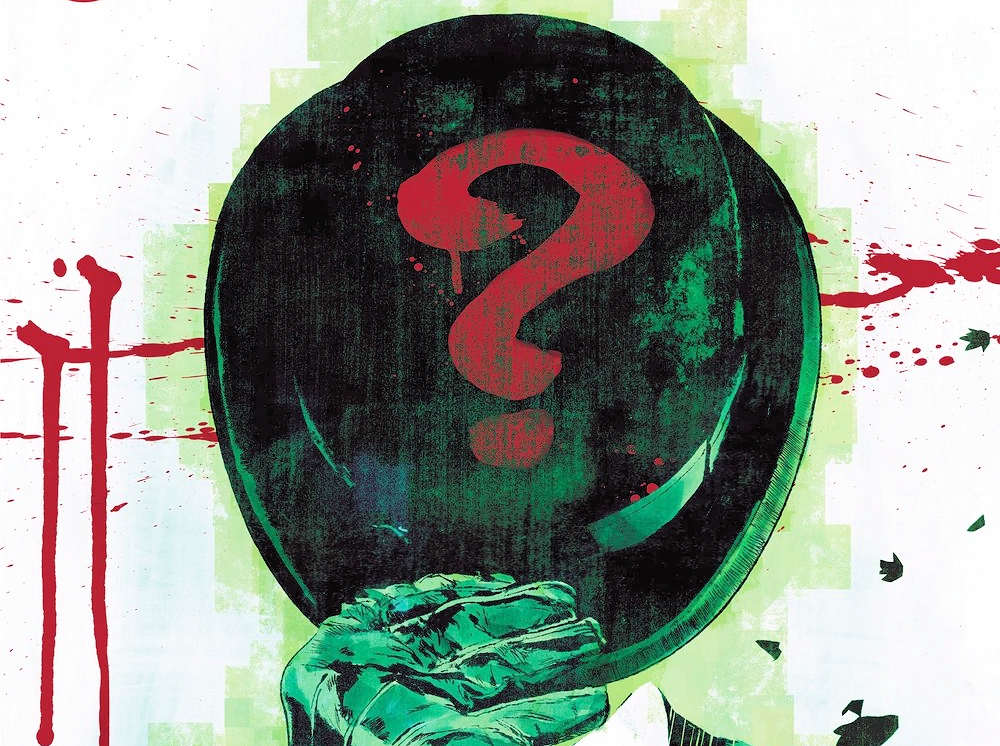

I’m disinterested in most of the big-budget comic-book-inspired movies, but as a former comic book collector I’m sometimes in the mood for a good superhero story. So this week I checked out a couple of good reads at my local library: Batman: One Bad Day – The Riddler by Tom King and Mitch Gerads, and The Batman Archives: Volume 1. One Bad Day – The Riddler is the first in a series of One Bad Day stories featuring some of Batman’s classic villains. King and Gerads have worked together on a number of projects. The art is brilliant and the story had me hooked until the final page with what I felt was a disappointing ending. Still, I enjoyed it enough that I want to track down more King/Gerads collaborations.

The Batman Archives: Volume 1 is a collection of the first Batman tales from Detective Comics, beginning with the Caped Crusader’s first appearance in Detective Comics #27 from March 1939. The work is credited to Bob Kane, but other writers and artists were involved, including Bill Finger and Jerry Robinson. It’s fascinating to compare those early stories with our contemporary Dark Knight mythos. The first Batman adventures were more conventional crime stories; one story begins when Batman is forced to stop and ask for directions after getting lost during an evening drive. The “weirdness” associated with the character was introduced over time. Gradually, the characters that continue to populate the Batman universe appear, like Robin (“The Boy Wonder!”), villains like Clayface and Hugo Strange, and the iconic utility belt. Other elements, Alfred and the Batcave, for instance, would come later. And Batman’s “no kill” policy is nowhere to be seen; it’s almost disturbing how casually Batman kills his opponents in these first stories.

I finally finished my slow read of The City in History by Lewis Mumford. What a book. At the time of publication, in 1961, Mumford was already observing or anticipating many of the self-inflicted traumas we’re living through today.

- P. 561: “Thus the very traits that have made the metropolis always seem at once alien and hostile to the folk in the hinterland are an essential part of the big city’s function: it has brought together, within relatively narrow compass, the diversity and variety of special cultures: at least in token quantities all races and cultures can be found here, along with their languages, their customs, their costumes, their typical cuisines: here the representatives of mankind first met face to face on neutral ground. The complexity and the cultural inclusiveness of the metropolis embody the complexity and variety of the world as a whole. Unconsciously the great capitals have been preparing mankind for the wider associations and unifications which the modern conquest of time and and space has made probable, if not inevitable.”

- P. 573: “The task of the coming city…is to put the highest concerns of man at the center of all his activities: to unite the scattered fragments of the human personality, turning artificially dismembered men – bureaucrats, specialists, ‘experts,’ depersonalized agents – into complete human beings, repairing the damage that has been done by vocational separation, by social segregation, by the over-cultivation of a favored function, by tribalisms and nationalisms, by the absence of organic partnerships and ideal purposes.”

Leave a comment