Welcome back to the Creative Life Adventure.

I’ve been thinking lately about how writers and filmmakers appropriate, reuse, reimagine, or in other ways make use of the work of others. It’s a fairly common dilemma in the movie industry, in particular. Movie studios seem to give us more prequels, sequels, revivals, and reboots, than they do truly original material. Sometimes it works, as with The Godfather Part II (1974). Sometimes it doesn’t, leading to my almost universal dislike of all Star Trek productions from 2009 forward. The reboot movies I just find offensive. And as much as I appreciate the casts of series like Discovery and Strange New Worlds, I just don’t like the writing and general directions of the stories. Too much emphasis on shouting, running, and explosions, overly stylized visual effects, a waterfall of Easter eggs, and characters eternally bogged down in soap-opera-level personal affairs, are no substitute for thoughtful stories with compelling characters.

I did enjoy Season 3 of Picard, though it fell prey, along with recurring Section 31 episodes throughout various series, to what appears to be an overall QAnon-ization of the franchise. I would rather the franchise be left alone than to keep cranking out such drivel as Star Trek Into Dumbness. Too many of these productions capture the superficial aspects of Star Trek and not the substance.

On the other hand, in a short time span, I’ve watched a film adaptation of a John D. MacDonald novel, read a continuation James Bond novel, and read a Sherlock Holmes pastiche. And I enjoyed them all. So what’s the difference? When is the appropriation of prior work acceptable?

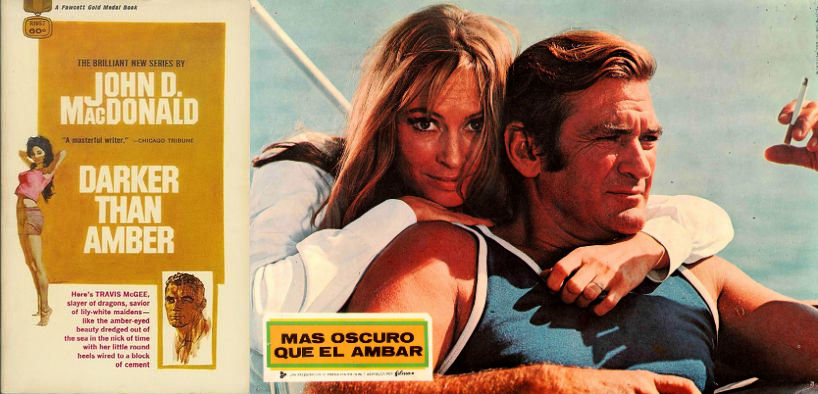

John D. MacDonald published Darker Than Amber in 1964. It was the seventh in what would become a 21-book series about the fictional Florida-based salvage consultant Travis McGee. The novel was adapted for the screen in 1970, directed by Robert Clouse, with Rod Taylor as McGee. This was only Clouse’s second film as a director. He went on to a successful career directing primarily action-adventure movies, particularly films featuring martial arts, including Enter the Dragon (1973), Black Belt Jones (1974), and The Big Brawl (1980). Taylor already had a long and varied list of film and television credits by 1970.

The film successfully captures the book’s plot: McGee and his best friend Meyer are fishing on the Florida coast one night when a woman is thrown off a nearby bridge. Rescuing the mysterious woman sets McGee on an adventure to terminate a highly profitable blackmail operation. The movie tells this story fairly well; I could imagine a series of such McGee adaptations fitting in well with the NBC Mystery Movie rotation of the early 1970s that included Columbo, McCloud, and McMillan & Wife. (In fact, a 1983 TV pilot starring Sam Elliott as McGee was very sloppily adapted from MacDonald’s The Empty Copper Sea.) McGee is a very physical character in the novels, and Rod Taylor depicts that quite well. But McGee was also a heavy thinker, sometimes to the point of being maudlin; the novels were narrated in the first person by McGee. McGee’s friendship with Meyer was profound. And the pillaging of Florida’s resources by human scavengers came up in nearly every book. The screen adaptation doesn’t capture those elements.

So Darker Than Amber, the movie, is hardly a classic and it’s not perfect as an adaptation. But it is a sincere effort made by people who clearly respected John D. MacDonald’s work. And that sincerity of effort begins to define when appropriation works and when it doesn’t. When Francis Ford Coppola adapted Mario Puzo‘s 1969 novel The Godfather, he respected Puzo’s work so much that he put the writer’s name on the movie’s opening title. And that sincerity is reflected in the outcome; if, as many claim, The Godfather: Part II exceeded the original film, certainly The Godfather exceeded the source novel.

Soon after I watched Darker Than Amber, I read William Boyd‘s 2013 James Bond continuation novel Solo. Boyd is a prolific writer of novels, screenplays, short stories, and other works. Prior to reading Solo, I had only read (and was captivated by) his 2002 novel Any Human Heart. It was successfully adapted for television; the fact that Boyd himself wrote the script probably had a lot to do with that success. Boyd was also not the first to write a Bond continuation story. Following the publication of Ian Fleming‘s final Bond work, Octopussy and the Living Daylights in 1966, Kingsley Amis wrote the first continuation novel, Colonel Sun in 1968. John Gardner published sixteen Bond novels between 1981 and 1996. From 1996 to 2002, Raymond Benson wrote six original Bond novels, three short stories, and three novelizations of Bond movies. (Novelizations of movies that are themselves based on novels must be a kind of double-appropriation.) Sebastian Faulks and Jeffery Deaver each published a single Bond novel, in 2008 and 2011 respectively. So the character of 007 had a long post-Fleming publication history before Boyd wrote his novel. It’s important to note that all of these authors were selected by Fleming’s estate, represented today by Ian Fleming Publications.

(It’s worth mentioning here that I have not read most of the Bond continuation novels, but my favorites are the trilogy written by Anthony Horowitz from 2015 to 2022. Charlie Higson wrote On His Majesty’s Secret Service – yikes! – in 2023.)

All of this is to demonstrate that by the time he wrote Solo, William Boyd was a highly regarded author and there was no longer anything scandalous about creating new stories with Ian Fleming’s character. More importantly, perhaps, Boyd was already an admirer of Fleming and his work. Any Human Heart is a work of fiction, but it references historic figures and events, and Ian Fleming plays a small but significant role in the novel. So Boyd had a similar respect for the source material he was working with as Francis Ford Coppola and Robert Crouse had for theirs. Boyd depicted Bond in a way that was faithful to Fleming’s books: “Bond is not just a superhero,” Boyd said. “He has flaws, he has weaknesses, he makes mistakes. … That was Fleming’s genius.”

At the same time, Boyd told his own story, filtered through his interests and experiences. Much of the novel takes place in the fictional African nation of Zanzarim, modeled after Biafra during the Nigerian Civil War of the late 1960s, and influenced by Boyd’s first-hand experience growing up in Nigeria. “I’m dealing with things and subjects I am interested in,” Boyd said. “It is very much my novel; it just features these characters invented by Fleming.” That refusal to be captivated by the source material, while still being respectful of it, is another crucial element. That’s the essential balance that Nicholas Meyer brought to Star Trek when he directed and/or co-wrote the films The Wrath of Khan, The Voyage Home, and The Undiscovered Country. “The chief contribution I brought to Star Trek II was a healthy disrespect,” Meyer said. “Star Trek was human allegory in a space format. That was both its strength and, ultimately, its weakness.” That’s a big reason those movies remain so watchable decades later.

It doesn’t hurt that Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan borrows heavily from Herman Melville‘s classic revenge tale Moby-Dick, with Admiral Kirk as the white whale pursued by Khan’s Captain Ahab. Khan even quotes twice from Moby-Dick, the last time with his dying breath: “To the last, I will grapple with thee. From hell’s heart, I stab at thee. For hate’s sake, I spit my last breath at thee.” From there, it seems natural to recall Ahab’s Wife: or, The Star-Gazer, Sena Jeter Naslund‘s novel about Una Spenser, Captain Ahab’s wife, who is barely mentioned in Melville’s book. With Naslund, Una gets a life or her own that is still situated in, and expands on, the world Melville imagined.

Star Trek isn’t the only franchise Meyer has had a hand in sustaining. In 1974, Meyer published The Seven-Per-Cent Solution, the first of what would become five (so far) Sherlock Holmes novels. I read this shortly after reading Solo. And, like literary Bond, this was hardly the first Holmes work published after (or even before) the 1930 death of the creator, Arthur Conan Doyle. For example, Sherlock Holmes Saving Mr. Venizelos was serialized in the Greek periodical Hellas in 1913. A considerable number of Holmes works, mostly short stories, were published in subsequent years. And of course, there have been numerous film and TV versions of Holmes, some more faithful to the original stories than others.

The Seven-Per-Cent Solution is a Holmes pastiche intended to emulate Arthur Conan Doyle’s style. The story is narrated in the first person by Dr. Watson, as were most of Doyle’s Holmes stories. Meyer references prior Holmes adventures, including “The Final Problem” and The Sign of Four. And like William Boyd, Meyer brought a long-time respect for the character’s creator to his storytelling. “I am overwhelmingly in debt to the genius of the late Sir Arthur Conan Doyle…” Meyer writes in his novel’s Acknowledgements. He reportedly became a fan of Holmes as a teenager. Also like Boyd, Meyer brings his own original interpretation to the franchise. He introduces Sigmund Freud in a significant role, and reinterprets the character of Professor Moriarty in a way that Holmes purists may not fully appreciate. (Meyer’s willingness to disrupt a franchise in this way would also show up in Star Trek II with the death of one of the major characters.) He even includes the dialog, “Come along, Watson, we haven’t a moment to lose,” which, to the best of my knowledge, was only used in cinematic versions of Holmes and not in Doyle’s stories.

Does this re-interpretation muddle a story that is otherwise appreciative of Doyle’s achievements? While I’m well familiar with the Bond novels, I confess that The Seven-Per-Cent Solution is the only Sherlock Holmes story I’ve read so far. That might make it easier for me to appreciate, even while I’m unable to grasp the significance of some of the in-franchise references. Fans in 1974 didn’t seem to mind: the book was a best-seller and was itself adapted for the big screen in 1976.

During this same time period, my wife read Percival Everett‘s widely-acclaimed recent novel James. The book describes the events and time period of Mark Twain‘s The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn from the perspective of Huck’s enslaved friend Jim. Some find Twain’s novel offensive because they consider it racist; others are offended because they don’t find it racist enough. Considering Huck Finn was published in the 1880s, it does come across as sympathetic to Jim, but it sure takes it’s time getting there. Scholars far wiser than me have debated Twain’s true intent and haven’t come to a satisfying consensus. Even though Huck Finn is widely considered to be Twain’s masterwork, I’ve always considered The Adventures of Tom Sawyer to be a superior book.

I’ve so far only read one of Percival Everett’s novels, Erasure, but that was enough to make me smile when I learned of the publication of James. I love the idea of shifting the perspective from Twain’s book and I’m glad Everett was the writer to do it. I’m a little surprised, and pleased, that I’ve read no real formal criticism for this re-imagining of a long-time literary “classic.” James, just like the successful adaptations and re-imaginings already mentioned, remains faithful to the source material; in interviews, Everett has been entirely sympathetic to Huck Finn’s creator, describing himself as being “in conversation with Twain.” He respects the original work while applying his own insights and experience to telling his own story. In this case, Everett also updates the original work by viewing it through the attitudes of our own present day. This is another essential quality to revisions or reimaginings of prior works: reminding us why the material is still relevant. Sadly, discrimination and systemic racism are still very much problems in 2024.

From Greek mythology to modern era literary works to such contemporary fictional worlds as James Bond and Star Trek, expanding the landscapes created by earlier writers and filmmakers is a reminder that fictional worlds belong to the imagination of everyone who spends time in them. That is the beauty and the danger of creating iconic works. Sometimes the results will be aggravating. It’s a mystery why studios keep giving money to J.J. (Just Joking!) Abrams, who seems to have made an entire career riding on the backs of much more creative people. But the trade-off for that is the pleasure of far more enduring works like James and The Seven-Per-Cent Solution. Even the near-misses, like Darker Than Amber, provide a useful dialogue on the nature of storytelling and world-building. A franchise “canon” is a fun idea as long as it remains entertaining but it isn’t worth losing sleep over. We should approach such reinventions judiciously, but we should be ready to embrace them when they work. After all, it’s entirely in our imagination.

Leave a comment