“Art is the greatest operating system our species has ever invented, a means of exploring consciousness, seen and unseen worlds.”

Jerry Saltz

“Introduction: The Medusa and the Pequod,” Art is Life

This week I’ve been reading art critic Jerry Saltz‘ 2022 book with the long subtitle: Art is Life: Icons and Iconoclasts, Visionaries and Vigilantes, and Flashes of Hope in the Night. The book is a collection of brief essays – most only about two pages – Saltz wrote from 1999 to 2021. While the writing is clearly oriented around art insiders, there is plenty here to appeal to novices like myself. Saltz writes about individual artists, art movements, museums, galleries, money, and politics. Writing about visual arts is inherently problematic – none of the work Saltz describes is reproduced in the book – so we amateurs need to do a fair amount of Web searching. The research is more than worth the effort, so take the time to absorb this book slowly. Saltz has introduced me to artists whose names I recognized despite little familiarity with their work – like Helen Frankenthaler and Gary Winogrand – as well as remarkable artists who I had never even heard of – such as Jacob Lawrence, Kara Walker, and Wilson Bentley. And his essays on George W. Bush – portrait artist! – and Thomas Kinkade are a hoot. Writers will especially appreciate Saltz’ essay, late in the book, about his long path to writing professionally about art.

“Most art is superficial. However, the aesthetic experience (that tinny off-putting term), the enigmatic interior place we go when we make or look at art, is still what it’s always been: complex, rich, rewarding, meaningful, and moving. It is a place we will always return to. A place, presumably, we all came from. A place, moreover, that tells us things we didn’t know we needed to know until we knew them.”

Jerry Saltz

“Keeping the Faith”

Art is Life

I don’t always agree with Saltz – and that’s good because art’s subjective nature is part of its beauty – and he dwells too often on works of a sexually graphic nature for my tastes. (The lack of illustrations is a plus in this case.) But I’m won over by Saltz’ enthusiasm and his compelling protests of the appropriation of counter-cultural or anti-establishment art by the wealthy wingnut class, while acknowledging his own role within that system. And he puts art in context with the discouraging times we live in – considering the 2016 presidential election the beginning of a “long American night” – while remaining hopeful that, as in dark times of the past, artists will defy the darkness and inspire us on toward better days.

“Yet perhaps…the artists of this new day may look upon the bravery and cowardice and cracks in the world that still control our fate – and transform them into a lasting vision of human possibility.”

Jerry Saltz

“Introduction: The Medusa and the Pequod,” Art is Life

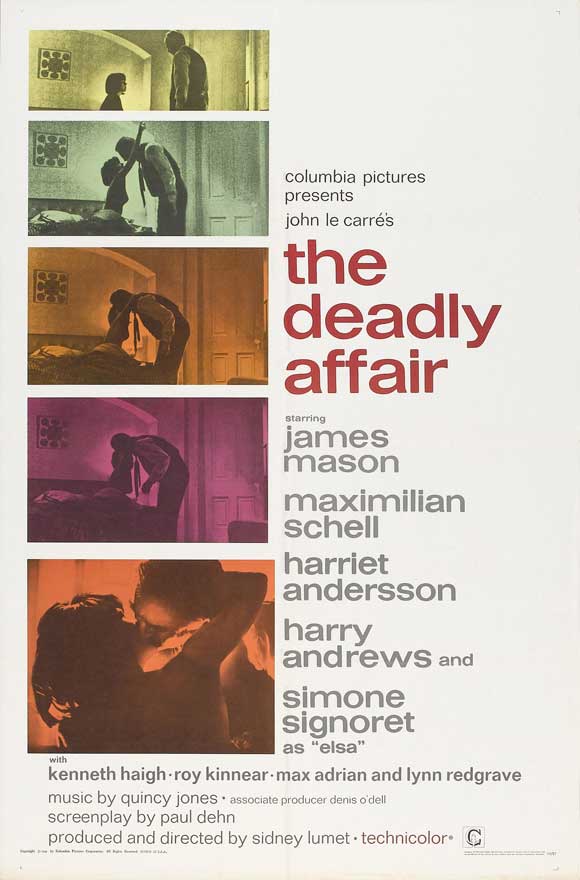

Call for a Deadly Affair:

“When you’re young, you hitch the wagon of whatever you believe in to whatever star looks likely to get the wagon moving.”

Robert Flemyng as Samuel Fennan

The Deadly Affair (1967)

I watched The Deadly Affair (1967) this week. It’s an adaptation of John le Carre‘s Call for the Dead, published in 1961. Call for the Dead was le Carre’s very first novel, and the first novel featuring the iconic anti-Bond George Smiley. The movie is a generally faithful adaptation of the book. Columbia Pictures produced The Deadly Affair, but Paramount owned the film rights to the George Smiley character as a result of producing The Spy Who Came in From the Cold (1965). That explains why the title is changed, and why George Smiley is now named Charles Dobbs. Likewise, Smiley’s steadfast colleague Peter Guillam from Call for the Dead becomes Bill Appleby in the movie. Discussion of a couple of other changes would involve spoilers.

Because it’s le Carre, the plot is not easy to summarize in only one or two sentences. Let’s just say Smiley/Dobbs is linked to a suicide that occurs under suspicious circumstances. A lot of the movie, like the book, involves conversations about behavior and motives, which is a lot more engrossing than it might appear on paper. The Deadly Affair is sometimes compared unfairly to The Spy Who Came in From the Cold, which most consider to be a superior film. Cold is excellent, of course, but for me its tone is simply too bleak.

Meanwhile, look at all the talent attached to The Deadly Affair. Directed by Sidney Lumet! James Mason is Smiley/Dobbs. Maximilian Schell is irresistibly suave as Dobbs’ former double-agent Dieter Frey. Harry Andrews is spot-on as the unflappable Inspector Mendel. Roy Kinnear (father of Rory) is the slimy Scarr. In her only scene, Lynn Redgrave is radiant as stage-hand Virgin. And I can’t say enough about Simone Signoret as Holocaust survivor Elsa Fennan; with brief screen time, Signoret is utterly convincing as a justifiably self-righteous survivor.

The music is one of my few gripes with The Deadly Affair. Quincy Jones composed a lovely bossa nova score, but the music’s bouncy tone doesn’t fit Dobbs’ staid world of Cold War espionage. And Mason is excellent as Dobbs, but far more emotive than the nearly-inert Smiley of the novel. (This can work in your favor if you haven’t read the book.) The cinematography, on the other hand, perfectly reflects the muted and shadowy nature of Dobbs’ life. Director of Photography was Freddie Young, who you may not recognize by name but you’ve likely seen his work, as he was the cinematographer on over 130 movies, including Lust for Life (1956), Lawrence of Arabia (1962), and You Only Live Twice (1967). In The Deadly Affair, Young pioneered the use of flashing, or pre-fogging, by carefully exposing the film to a small amount of light before use, reducing the film’s color palette in a way that Lumet described as “colorless color.” Vilmos Zsigmond used the technique later in McCabe & Mrs. Miller (1971) and The Long Goodbye (1973).

I was initially disappointed with the movie’s final scene, but I’m already having second thoughts about that. This is one of those movies that I can’t stop thinking about and that I already want to see a second time. And it has me eager to revisit all of le Carre’s George Smiley stories. The Deadly Affair is currently streaming on Tubi.

Not Gilligan’s Island

Finally, a couple of weeks ago I wrote about the 1955 movie 5 Against the House, directed by Phil Karlson. I noted that Karlson directed four movies released that year, and this week I watched another of them, Hell’s Island. Hell’s Island is definitely not as thought-provoking as 5 Against the House, but it is still good escapist entertainment. The story involves a classic down-on-his-luck protagonist – if they didn’t start out unlucky we would have no reason to sympathize with them – who is hired by a mysterious stranger to search for a lost ruby on a Caribbean island. Mayhem ensues. The film opens with the massive spoiler that the hero survives, but it doesn’t matter, because the first thing he does when waking from surgery is light up a cigarette while still on the operating table. That’s about as noir as a film can get.

John Payne is just the right amount of rugged as the wayward protagonist. (Just try to ignore Payne’s politics as a supporter of the original wingnut himself, Barry Goldwater.) Francis L. Sullivan as the secretive Barzland is sinister without descending into caricature. Paul Cicerni doesn’t get much time as Eduardo Martin, but he is brilliant and the entire film revolves around his character’s revelations. A few times I found myself imagining Humphrey Bogart, Sydney Greenstreet, and Peter Lorre in these roles – which isn’t surprising because director Karlson described Hell’s Island as a variation of The Maltese Falcon. That doesn’t diminish Hell’s Island as exactly what I described above – good escapist entertainment. I watched a slightly choppy version on YouTube, but the movie was filmed in VistaVision and you should watch a cleaner version if you can find one.

Leave a comment