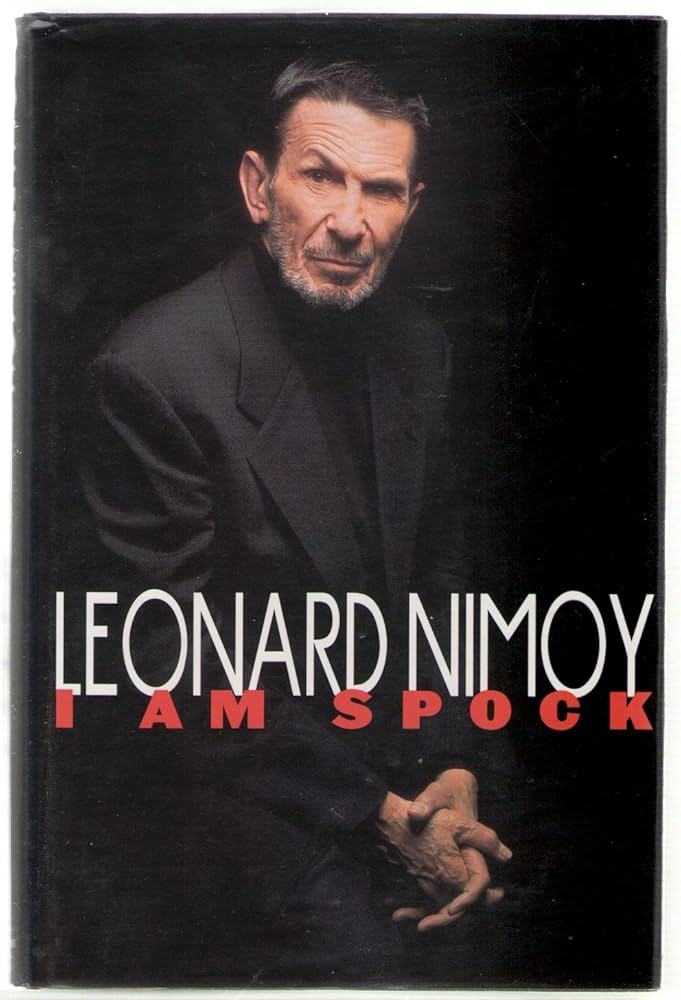

“Who among us does not understand what it is to be an outsider, separate?”

Leonard Nimoy

I Am Spock

This week I read the memoir I Am Spock by Leonard Nimoy. It was published in 1995, so I’m not sure what I was waiting for. I understand the title’s double-meaning, even though I haven’t been able to find an affordable copy of Nimoy’s earlier memoir I Am Not Spock. I never met Nimoy at his numerous convention appearances, but I’ve seen plenty of interviews and, of course, I’ve seen the touching documentary For the Love of Spock (2016). So while I can’t confirm whether or not I Am Spock relied on a ghost writer, Nimoy’s warmth and enthusiasm come through perfectly in the writing. If I have any nitpick with the book, it’s that it focuses almost entirely on Star Trek, with only brief digressions into early biography, stage work, Mission: Impossible, his later directing work, etc. That’s a very trivial concern, because in fairness the book’s title establishes expectations. That also means Nimoy doesn’t stray much into personal matters or gossip, something I respect in a celebrity memoir. And while many of the Star Trek anecdotes will already be familiar to long-time fans, I did find some new information here, and hearing everything from Nimoy’s perspective is well worth the journey. Learning about Nimoy’s thoughtful and courageous approach to his career is also, well, fascinating. I highly recommend I Am Spock for any Star Trek fans. Late in the book, Nimoy writes, “I can only hope that, once in a while, when people look at Spock’s visage, they might sometimes think of me.” This reader can think of no one else.

“As the plot [of Star Trek II] advanced, the classic theme came ever more sharply into focus: How hatred and vengeance leave a path of destruction in an ever-widening circle.”

Leonard Nimoy

I Am Spock

Don’t Sleep in the Sleeping Car

I was able to watch Costa-Gavras‘ first feature film, The Sleeping Car Murders (1965). I’m a huge fan of his political thrillers Z (1969) and State of Siege (1972). I’ve also enjoyed some of his later films like Missing (1982) and Mad City (1997). The Sleeping Car Murders is adapted from a novel by Sébastien Japrisot, and is more of a straightforward mystery with little of the political or social commentary in many of Costa-Gavras’ later films. The story begins with the murder of a passenger in the sleeper car of a Paris-bound train. The other sleeper car passengers are both witnesses and suspects. Yves Montand plays the police inspector assigned to the case. The movie takes a bit to get going, but does a fine job of capturing the various pressures on the detective and the eccentric lives of the passengers – a reminder that we can all seem eccentric in the eyes of others.

Last week I wrote about my complete failure to be surprised at the “surprise” ending of Witness for the Prosecution (1957). In contrast, the mystery in The Sleeping Car Murders kept me in genuine suspense. The conclusion includes a thrilling car chase in Paris and the movie ends with a brilliant tracking shot. I was reduced to watching an English-dubbed version; I highly recommend watching it in the original French with subtitles if possible.

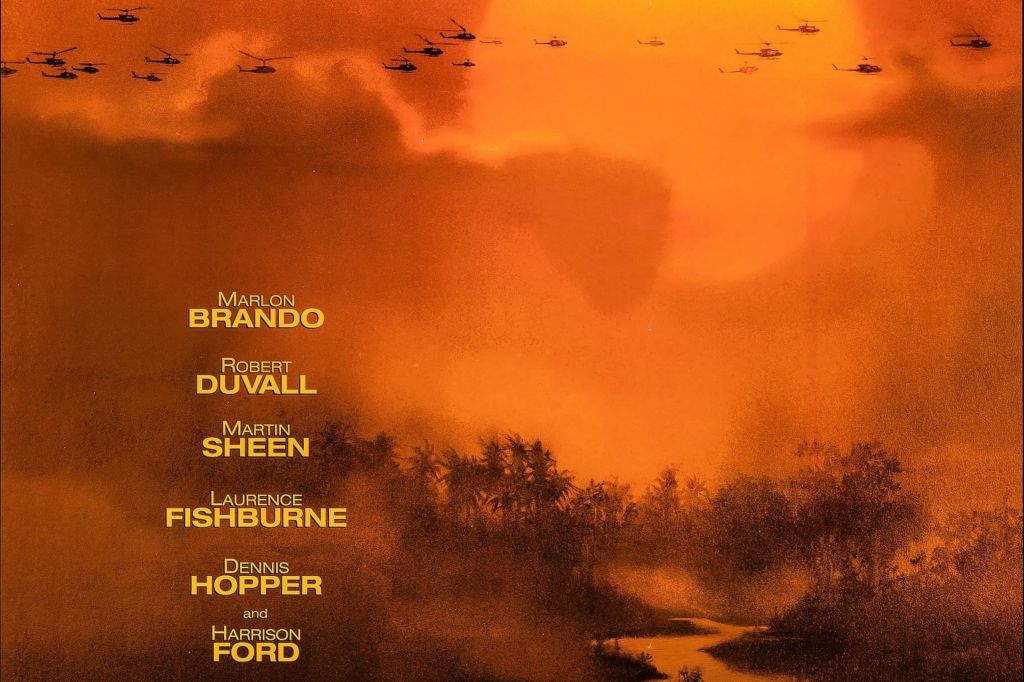

Mega-Apocalypse

In anticipation of Francis Ford Coppola‘s Megalopolis (2024), I re-watched Apocalypse Now Redux (2001), the super-extended version of 1979’s Apocalypse Now. (I have yet to see 2019’s Final Cut.) This is the most brilliantly bonkers movie I’ve ever seen, and if you’ve watched any of the versions you understand. So much has been written about Apocalypse Now that it’s unlikely I can add anything original, but I’m so taken by the experience that I still want to try.

Coppola’s inspiration from Joseph Conrad‘s Heart of Darkness is well known. Less talked about influences include Lord of the Flies by William Golding, Moby-Dick by Herman Melville, and The Golden Bough by James Frazer. (Marlon Brando‘s Colonel Kurtz has a copy of The Golden Bough in his compound – this article explains some of the book’s influence on the movie’s final act.) I even see some Catch-22 influence, especially in the shot of Coppola directing Martin Sheen as a news director directing Willard.

In particular, at the moment, I’m thinking of the French plantation sequence, absent from the original and criticized by some as disruptive to the narrative flow of Redux. I love the plantation sequence and believe it fits perfectly in the movie’s grab-bag unraveling of history. Kilgore and his surfing helicopter pilots remind us that we’re way past the Beach Boys innocence of the early rock era. Were Playboy Playmates dispatched to entertain the troops in World War II? Probably not, we’re past that “good” war, also. So it doesn’t hurt to have a reminder of what we’ve not gotten past – good old-fashioned colonialism, demonstrated by Willard and his men having an awkward dinner with demented French plantation owners deep in the Vietnamese jungle. The land has “belonged” to the de Marais family for generations – France colonized Vietnam during the days of Napoleon III – and they insist that they will never leave as the world burns around them.

- “They were hanging on by their fingernails, but so were we,” Willard says in voice-over. “We just had more fingernails in it.” The U.S. was already heavily financing the French action in Indochina by the time of Dien Bien Phu in 1954; who is really paying for the upkeep on this plantation the de Marais family built on Vietnamese land?

- Watch Willard shield his eyes as the sun sets on the plantation; the long daytime of Imperial Europe is over and only Willard can see it.

- “Why don’t you Americans learn from us? From our mistakes?” one of the French occupiers demands, the most honest member of the tribe. France failed in Indochina – Old Europe was never the same after the World Wars – but blustery America will do no better in Vietnam. (This tracks directly to Kurtz’ claim in the final act that the U.S. was not savage enough to win the war. Wouldn’t it have been better to never fight the war in the first place?)

- “We want to stay here because it’s ours, it belongs to us. It keeps our family together,” the patriarch Hubert says to a nearly empty table. Most of the family has already left in anger – the European empire is reduced to a handful of squabbling nation-states.

- Still, Willard can’t resist a night of morphine with Roxanne. The U.S. suffers the same colonial fever dream as France. Colonialism is in the DNA of any nation born from uber-imperialist England.

There’s more that could be said about this sequence, probably enough to fill a book. Certainly discussion of the overall film could fill many volumes (and already has). For example, the water buffalo scene late in the movie is horrific and, in my opinion, reflects poorly on Coppola; this is one of my few complaints with the overall work. Coppola himself has said that Apocalypse Now – or Redux, which I consider a legitimate improvement on the original – is not an anti-war movie, and yet it perfectly captures the insanity of humans making war on each other. Apocalypse Now Redux is currently streaming on Plex. And I also recommend this fascinating interview with Coppola on Letterboxd, with great insights into the director’s creative process.

Leave a comment