“December 27 [1949], a month before President Truman will announce development of a ‘super-bomb’ five hundred times more powerful than those dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the air force concludes a two-year investigation by denying that the country is being probed and spied on by alien spaceships from outer space.”

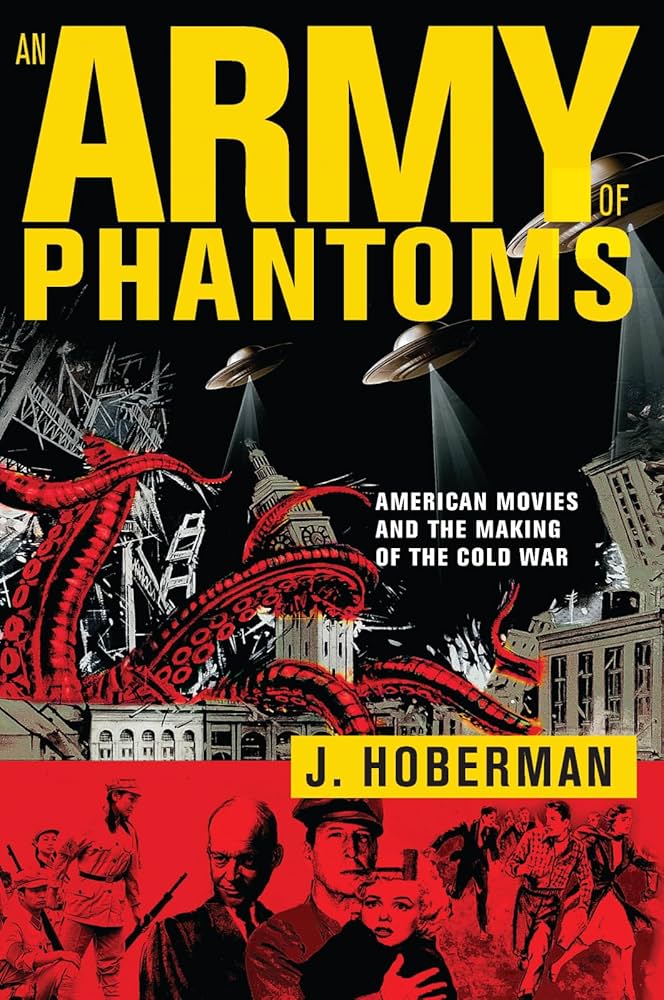

—An Army of Phantoms by J. Hoberman–

One of my favorite reading experiences of 2023 was J. Hoberman‘s The Dream Life: Movies, Media, and the Mythology of the Sixties, part of a trilogy of books on the intersection of movies and politics during the Cold War. Hoberman was a long-time film critic for The Village Voice and he continues to write about movies and film history. Now I’m reading the next book in the trilogy, in order of publication, An Army of Phantoms: American Movies and the Making of the Cold War. Hoberman’s goal is not a conventional film history, but to study the ways in which movies and politics influence each other. Covering the years from the end of World War II through 1956, what stands out the most about this time period is how relentlessly, and mindlessly, obsessive so many people were with slapping the term “communist” on everyone or everything they didn’t like. (In other words, not so different from today.) Hoberman explores the motivations behind, the making of, and the impact of, films such as Fort Apache (1948), The Next Voice You Hear… (1950), High Noon (1952), It Came From Outer Space (1953), and a long list of other movies. An Army of Phantoms is a must-read for movie buffs and anyone interested in Cold War history.

“The century declared by Time to be America’s approaches its midpoint amid dreams of disaster, memories of cosmic cataclysm, the suggestion of vast conspiracies, visions of extraterrestrial visitation, a sense of impending jihad, and intimations of Judgment Day.”

—An Army of Phantoms by J. Hoberman–

The Age of Claudel

My mental wanderings this week took me to the life of Camille Claudel (1864 – 1943), and I immediately felt ignorant for not already being familiar with her art. I’ve even been to Musée Rodin in Paris, where there is a room dedicated to Claudel’s work. In fairness, the museum was crowded that day and I focused my attention on the exterior grounds. (Even better would have been a visit to Musée Camille Claudel in Claudel’s birthplace of Nogent-sur-Seine, about 65 miles from Paris.) Like Auguste Rodin (1840 – 1917), Claudel was a sculptor. She was also Rodin’s employee, lover, and student. The two artists clearly influenced each other’s work, though to what extent is debatable. But Claudel’s sculptures are breathtaking; some of her best-known works are The Waltz, The Mature Age (which we’ll return to), Sakuntala, and Deep Thought (far more emotionally compelling than Rodin’s own similarly-titled The Thinker).

No biographies of Claudel are available to me at the moment, so I turned to the two feature films on her life, both currently streaming on Kanopy. Because Claudel’s tragic outcome is already known – she spent the last thirty years of her life in an asylum – the movies don’t offer suspense so much as a contemplation of the way Claudel’s passion and eccentricity were regarded in a male-dominated world of double standards. Camille Claudel (1988) features Isabelle Adjani as Claudel from about the age of 20 until she was forcibly institutionalized in 1913. We can only expect so much when a single film tries to capture an entire life, and while the film doesn’t entirely come together – with a run-time of nearly three hours – Camille Claudel powerfully depicts Claudel’s troubled life. Some first-hand accounts of the time contradict one another, so the movie wisely remains vague on the extent to which Claudel’s alleged madness was caused by Rodin’s behavior, the misogyny of the 1800s Paris art world, or genetics (witness her mother’s increasingly hyperbolic criticisms of her daughter’s life choices). Claudel’s pregnancy by Rodin (played by Gérard Depardieu, how ironic!) and subsequent abortion, couldn’t have helped – Rodin refused to leave his long-established life partner Rose Beuret, reducing Claudel to the status of mistress.

Still, at least in the context of the film, we know the point when Claudel’s fate is sealed. It’s not the abortion, or her departure from Rodin to more aggressively pursue her own work. No, it’s at about the midpoint of the film, when a group, all men, admires Claudel’s sculpture of Rodin himself. Rodin, not looking very confident, says, “Mademoiselle Claudel has become a master.” And another says, “She’s got the talent of a man. She’s a witch.” No woman in such a culture could have a happy outcome. Claudel’s father, the only relative who seems to have truly supported her work, died on 3 March 1913. Claudel was institutionalized only a week later.

Meanwhile, Camille Claudel 1915 (2013), featuring Juliette Binoche as Claudel, could almost serve as a sequel to the earlier film. Camille Claudel ends with Claudel’s incarceration, while Camille Claudel 1915, as the title indicates, takes place early in Claudel’s forced stay at an asylum in Montfavet, near Avignon in the south of France. (Claudel was initially confined in Paris, but she and many other “patients” were moved when the Germans approached Paris during World War I.) Binoche’s portrayal is quieter than Adjani’s and the later film is even more somber than the first. We experience Claudel’s anguish, unable to exercise her creative desires and shunned by her family – records indicate that Claudel’s mother and brother, Paul, were the primary instigators of her admission to the asylum. A good part of the movie’s drama orients around an expected visit from Paul, who appears to suffer his own form of mental illness, in the form of an unfocused religious fundamentalism. (In real life, a friend of Rodin’s, Mathias Morhardt, described Paul as a “simpleton,” and blamed him for Claudel’s asylum status.) Again, we know the ending. The power of Camille Claudel 1915 lies with Binoche’s brilliant performance, including two long takes in close-up of Binoche, as Claudel, tearing her heart out to the various deaf ears around her – the caretaker nuns, the other patients, and the psychiatrist who even bears some resemblance to Rodin. In both films, Claudel blames Rodin for organizing a denial of the professional credibility she clearly deserves.

Many have speculated on a strong correlation between creativity and mental illness over the years. This thinking has long-since been debunked (read, for example, Creativity: The Psychology of Discovery and Invention by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi), but that wasn’t necessarily true of Claudel’s time. When a child admires her work in Camille Claudel, he asks, “How did you know there were people inside the big white rock?” Claudel has no answer. She just knew. She perhaps knew with more insight than Rodin did, and that would certainly have appeared threatening to Rodin and the establishment. This is spelled out at another point in the movie, when Rodin tells Claudel, “I want you to do what I tell you to do.” No true artist could tolerate such a condition. That was made clear by Claudel’s work that seems to have permanently divided the two, The Mature Age. The sculpture shows a man turning his back to a younger woman while being led away by an older woman. (Rose Beuret was twenty years older than Claudel but still four years younger than Rodin.) Claudel is said to have described the sculpture as a representation of Destiny. Rodin saw something highly personal, his own waffling between Claudel and Beuret. It has been speculated that Rodin may have pulled strings to hinder Claudel’s career after he saw The Mature Age. Cinematic Claudel has the perfect response to Rodin’s narcissistic interpretation: “You’re wrong to think it’s about you. You’re a sculptor, Rodin, not a sculpture. You ought to know. I am that old woman with nothing on her bones. And the aging young girl… that’s also me. And the man is me, too. Not you. I gave him my toughness. He gave me his emptiness in return. There you are… three times me.”

Leave a comment