Note: This essay includes spoilers for the movie Body Double (1984) and the novels The Color of Money by Walter Tevis (1984) and The Sportswriter by Richard Ford (1986).

“Middle age doesn’t exist, Fast Eddie. It’s an invention of the media, like halitosis. It’s something they tame people with.”

—The Color of Money by Walter Tevis–

In my previous post, I blamed a lot of the world’s problems on the Reagan Administration. I see no reason to abandon that premise. Every decade in human history has its share of tumultuousness – we humans like to make life difficult – but the Reagan/Thatcher years set the course for an extreme pro-business culture combined with an illusion of hyper-individuality. It was as if the conformity associated with the 1950s merged with the radical youth culture of the 1960s and gave rise to a society that encouraged individual expression within a very narrow region of the pesky bell curve that is so often used to codify the human experience. (This, for example, gave us corporations that attach their logo to pride parades while donating to anti-LGBTQ politicians.) What should have been the last gasp of the white male stranglehold on power turned into the beginning of a decades-long “culture war” concocted to divide the electorate and consolidate power in the hands of the already-powerful. The mid-decade was also a peak of Cold War activity: the U.S. firmly backed the mujahideen (forerunner of the Taliban!) against the Soviet Union in Afghanistan; Reagan proposed the Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI) in 1983; Mikhail Gorbachev became leader of the USSR in 1985.

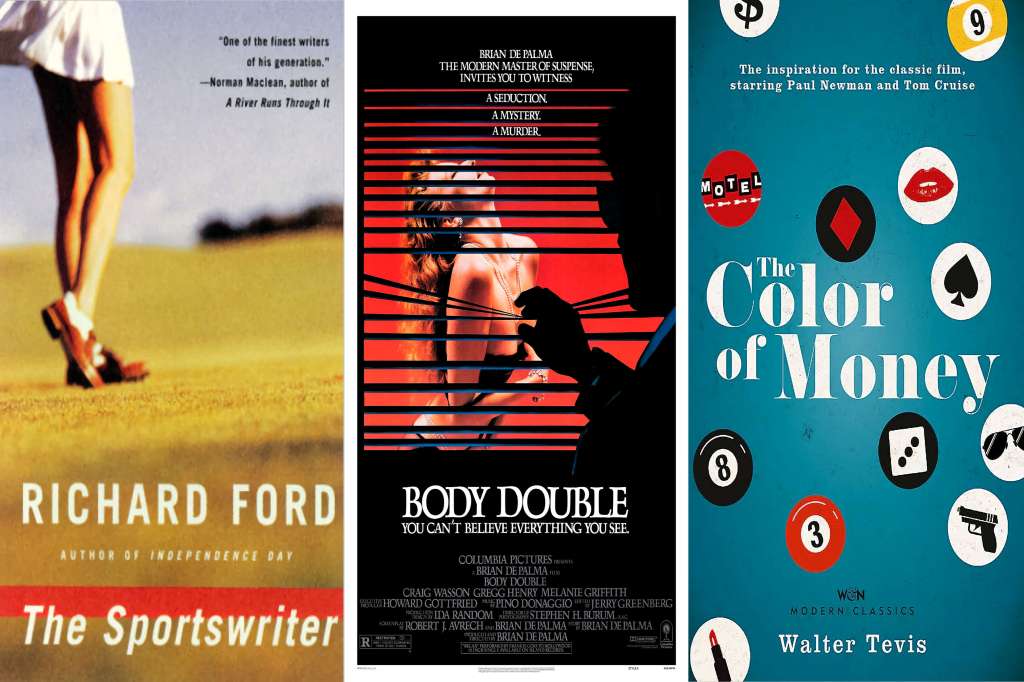

I’ve recently re-watched Brian De Palma‘s Body Double (1984), and read the novels The Color of Money by Walter Tevis and The Sportswriter by Richard Ford, published in 1984 and 1986, respectively. While all three are very different stories, they are all stories of male suffering firmly anchored in the 1980s. In Body Double, struggling actor Jake Scully (Craig Wasson) is set up as an unreliable witness to a murder. In The Color of Money, former pool hustler Fast Eddie Felson finds himself unmoored by a divorce that puts him in a professional freefall. And in The Sportswriter, Frank Bascombe remains in denial of the emotional trauma resulting from the death of a son and a divorce.

Source Material

“A life can simply change the way a day changes – sunny to rain, like the song says. But it can also change again.”

—The Sportswriter by Richard Ford–

Body Double is entirely a tale for the screen, written by De Palma and screenwriter Robert J. Avrech, and following in the footsteps of previous erotic thrillers like Dressed to Kill (1980), also by De Palma, Body Heat (1981), and The Postman Always Rings Twice (1981). Like much of Brian De Palma’s work, Body Double was heavily influenced by the movies of Alfred Hitchcock, who also devoted a fair amount of attention to male suffering. De Palma was also influenced by the struggle to avoid an X rating on his prior film, Scarface (1983). “They think Scarface is violent?” De Palma said. “They think my other movies were erotic? Wait until they see Body Double.” In reality, relative to more contemporary films, Body Double does not seem that graphic, but a porn industry sub-plot gives the film a more visceral tone.

The Color of Money was Walter Tevis’ final novel, and a sequel to his 1959 book The Hustler. The Sportswriter, conversely, became the first in a series of five books focused on the character of Frank Bascombe. The writing styles are quite different: The prose in The Color of Money is lean and, while Fast Eddie is plenty introspective, he keeps moving forward at all times, while The Sportswriter‘s text is far more elaborate and spends considerable time inside Frank Bascombe’s head instead of the outside world. This may be partly a result of the writers coming from two different generations: Walter Tevis was born in 1928, while Richard Ford was born in 1944. Also, Tevis drew heavily on his own experiences working in a pool hall and struggling with alcoholism. In college, he studied under A.B. Guthrie, Jr., who started out as a journalist before turning to fiction, bringing a journalistic style to such novels as The Big Sky and The Way West. (Guthrie primarily wrote westerns, and The Color of Money has thematic overlap with westerns, portraying the capitalistic taming of a culture and “shootouts” over a pool table.) Ford, on the other hand, studied under Oakley Hall and E.L. Doctorow at the University of California, Irvine, as did that master of wordiness, Michael Chabon. These stylistic differences might help explain why The Color of Money was (very loosely) adapted for the screen, while The Sportswriter, so far, has not been.

Common Differences

“What are you, some kind of method actor?”

–Al Israel as Corso the Director, Body Double—

The result of all of this is three very different protagonists who still share considerable DNA. They are different ages: Jake Scully’s age isn’t disclosed, but Craig Wasson was 30 in 1984; Fast Eddie is 50; Bascombe is a few days away from his 39th birthday. Yet all three characters are at a kind of mid-life crisis. They are outside the approved region of the bell curve, outliers by chance or choice. Scully is an actor in B horror movies. Fast Eddie is a former pool hustler managing a pool hall in Lexington, Kentucky, having not fully recovered from the events of The Hustler. And Bascombe is a sportswriter for a Sports Illustrated type of magazine; he claims to be good at his job, and to enjoy it, but he is an unreliable narrator and the evidence is not convincing. After a disastrous interview with a justifiably angry paraplegic athlete, he tries and fails to turn the tragedy into a kind of Reagan-positivism fable.

As a result of their non-conformity, the three protagonists are disconnected from much of society. This is most notable in Scully, who suffers claustrophobia and is fired from his acting job as a result. Also homeless after leaving his girlfriend (more on that later), Scully is an easy target for the wily Sam Bouchard (Gregg Henry). Bascombe, as indicated, has clearly not recovered from the grief of his son’s death and subsequent divorce. But ground zero for his grief is his failed writing career – a successful short story collection and an unfinished novel that sent him to sports writing in the first place. He lives in the Jersey suburbs and, by his own admission, is generally nervous about going into New York City where his employer is headquartered. He is a half-hearted participant in a divorced men’s group and nearly every conversation he has feels awkward. Of the three protagonists, Fast Eddie Felson is the most open to the world, soaking up, sometimes reluctantly, the advice he receives from Minnesota Fats and Boomer, and learning the use of a new pool cue. But he loses his pool hall to his ex-wife in a divorce and, at age 50, playing pool and hustling are his only skills. He feels invisible to the TV cameras filming his early pool matches with Minnesota Fats. And he develops a “grass-is-greener” dynamic with the academic friends of his new girlfriend Arabella – he admires their stable and comfortable lives, while they regard him as a rebel and envy his lack of attachments.

Modern Women

“I understand you’re sick and you’re a liar and you need professional help, and I don’t like being yelled at.”

–Melanie Griffith as Holly Body, Body Double—

As a result of all this disconnectedness, all three men are heavily defined by their relationships with women, another common theme in male suffering stories. Each character undertakes a new relationship while striving for professional and emotional independence. However, all three also have a voyeuristic tendency that manifests itself in those relationships. Scully is forced to leave his girlfriend’s house when he finds her cheating on him. He is happy to watch the strip-tease neighbor through a telescope from the exotic Chemosphere house where Sam Bouchard allows him to stay. It seems inevitable that Scully will end up on the set of a porn movie, the ultimate voyeuristic experience. Fast Eddie, on the other hand, doubts that he is good enough for the refined and British Arabella, feeling he has to find his way professionally before being deserving of her love. He is also envious of the newspaper clippings Arabella keeps of her former love, the equally refined young professor who was killed by a reckless driver. As for Bascombe, he is already divorced when The Sportswriter begins, but remains somewhat obsessed with his ex-wife – who he refers to exclusively as X, talk about denial! – and makes more than one inappropriate proposition to her during the course of the novel. Then there is his desperate, and dangerous, marriage proposal to new main squeeze Vicki, who soured on him after catching him rifling through her purse and obsessing over her ex-husband. X and Vicki are both smart enough to resist Bascombe, recognizing the amount of self-work he needs. Women became more present in the workforce during the 1980s, and of these three stories, Body Double, despite accusations of misogyny, probably expresses this in the most progressive way: passive Gloria suffers the death of an outdated gender trope, but Holly Body is tough and independent, and she remains alive (and fully clothed!) at movie’s end.

Harsh Times

“In a business you could pretend that skill and determination had brought you along when it had only been luck and muddle; a pool hustler did not have the freedom to believe that. There were well-paid incompetents everywhere living rich lives.”

—The Color of Money by Richard Tevis–

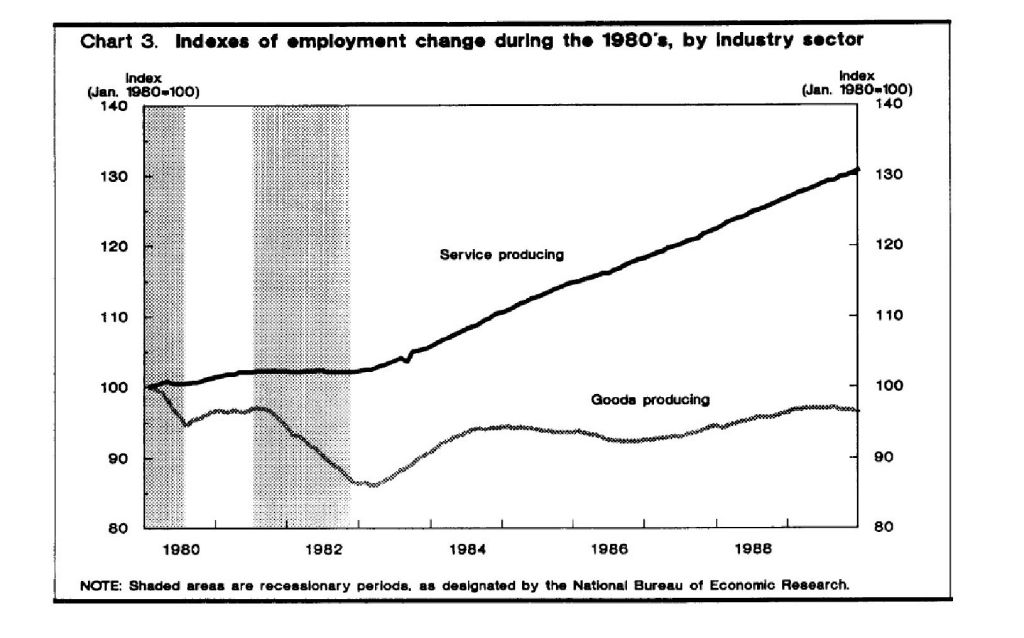

One reason for all this disorientation is the changing times the characters live in. The 1980s began with a recession and saw lasting changes to the labor market. Thanks in part to pro-business economic policies, technological “advances,” and increasing globalization, manufacturing and mining jobs declined and service sector jobs became more prominent in the overall economy. While Scully, Fast Eddie, and Bascombe are not directly affected by this, the “rust belt” evidence is all around them, particularly as Fast Eddie tours the country’s pool halls and Bascombe makes his ill-fated trip to Detroit. Socioeconomic changes are visible in unintended ways, also. In The Sportswriter, every woman is referred to as a “girl,” and every Black character is identified a little too frequently as being Black, in ways that would seem awkward in later years. Fast Eddie is practically a poster child for what we now call the gig economy; his attempt at opening a folk art gallery introduces us to artists who are equally struggling in the “Decade of Greed.” They are desperate to sell their work, but trying in vain to avoid becoming commodities. Worse, Fast Eddie finds that pool itself has changed – he wants to shoot “straight” pool, but he gradually understands that nine-ball is all the rage and the only way he can make real money in tournaments. Scully is in the midst of a home entertainment revolution that gave rise to music videos – he stumbles onto the filming of a music video for “Relax” by Frankie Goes to Hollywood, a song and group that existed outside the movie. At the same time, VHS brought on-demand movies into homes on an unprecedented scale; this trend would widely expand the market for B horror movies that Scully specializes in, but did the same for the porn industry he immerses himself in while searching for Melanie Griffith‘s Holly Body.

These kinds of stories – the personalization of cultural transformations – are some of my favorites. This is the template for one classic tale after another. Will Don Corleone yield to pressure and join the Five Families in drug trafficking? Why is bookseller Barley Blair surprised that his bold political talk invites Soviet dissidents to his doorstep? How will galactic cold warrior Captain Kirk survive a widespread movement for peace with the Klingons?* Global and regional events impact individuals, and changing times overtake us all sooner or later. Society might sometimes choose poorly – Betamax was superior to VHS, and straight pool is a more gentlemanly game than nine-ball – but human error is inevitable and sometimes the best we can do is survive the day and look for wisdom along the way.

(* The Godfather (1972), The Russia House by John le Carre, and Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country (1991))

Better Days

“A change to pleasant surroundings is always a tonic for creativity.”

—The Sportswriter by Richard Ford–

As a result, each story ends with the hero a more complete individual. The futures of Scully and Fast Eddie are left to our imagination. Scully is presumably bound for a happy relationship with Holly Body and a more stable movie career, now a participant rather than a voyeur, vividly demonstrated in the extreme close-up of his hand over the body double’s breast. We get a hint that Fast Eddie’s future might be a bit darker, with possible foreshadowing in the final scene of the older man in the casino. On the other hand, we can easily learn Frank Bascombe’s future, because Richard Ford wrote a sequel to The Sportswriter, the Pulitzer Prize-winning Independence Day, to be followed by three more Bascombe stories. Either way, all three stories hold up reasonably well decades later, particularly The Color of Money, yet each is a unique time capsule of life in the 1980s. “Male suffering” would finally, thankfully, become boring enough that more diverse stories have become increasingly common in the decades since. That’s the thing about these times of ours – they never stop changing, and neither do we.

Leave a comment