“That’s fine!”

–Buster Crabbe as Flash, upon learning that the earth won’t be destroyed after all, in Flash Gordon (1936)–

Our attention spans are getting shorter.

If you haven’t already drifted off, the reality of variable attention spans is debatable, but this article from the American Psychological Association indicates that there is good reason for concern – for example, frequent attention-shifting can increase stress levels. The article also provides historic context. Psychologist and philosopher William James was talking about human attention span back in the 1800s, linking it to the very essence of free will: “[Free will] relates solely to the amount of effort of attention or consent which we can at any time put forth.” Our time is the most valuable asset we possess, and the use of our time is determined by how we direct our attention, or how it’s directed for us. I’ve been thinking about attention spans in the context of popular entertainment after watching one of the classic movie serials, Flash Gordon (1936), the first of three serials featuring Buster Crabbe as the iconic hero.

The serial format wasn’t new in 1936. Some of the best known novels of the 1800s and early 1900s were first published as serials, including many of Charles Dickens‘ novels, The Count of Monte Cristo by Alexandre Dumas, Uncle Tom’s Cabin by Harriet Beecher Stowe, Middlemarch by George Eliot, and The Hound of the Baskervilles by Arthur Conan Doyle. Syndicated comic strips, the medium in which Flash Gordon originated in 1934, were essentially comic books delivered in daily or weekly episodes. Radio soap operas – called that because of soap-maker sponsors like Proctor & Gamble, Colgate-Palmolive, and Lever Brothers – were very popular in the 1930s and 1940s, before TV came along and visualized the experience with daytime and, later, prime-time soap operas. Remember Dallas and the “Who shot J.R.?” mania of 1980? The ongoing storyline of a serial or soap opera allows for more depth of storytelling and character development than a stand-alone episode, while delivering regular adrenaline hits with “To be continued” endings. The serial format remains popular to this day. Recent limited run TV series like Mr. Robot and The Old Man relied heavily on episodic cliffhangers. And what is a Mission Impossible movie but a feature-length compilation of thematically linked action-adventure short stories?

Presenting a story in chapters released over time is almost entirely about maximizing limited attention span. Binge-watching may be popular, but it is primarily an exercise in screen-staring and background noise, and rarely involves intentional viewing. It’s much easier to focus on periodic 30- or 60-minute stories than a 4- or 5-hour story. And no matter how compelling a book is, it’s easier to stay alert reading one or two chapters at a time. It may seem contradictory that movie run-times have increased in recent decades, at least among the most popular movies. Just look at the Batman franchise: we’ve gone from Batman (1989), at 126 minutes, to Batman Begins (2005), at 140 minutes, to The Batman (2022), at 176 minutes. And with one exception, every Mission Impossible movie has been longer than the previous installment. (It looks like 2025’s The Final Reckoning will be the second exception, with a projected run-time equal to 2023’s Dead Reckoning.) But increased movie length is likely correlated with the modern-day ease of on-demand streaming; we no longer have to watch the entire movie before being evicted from the theater.

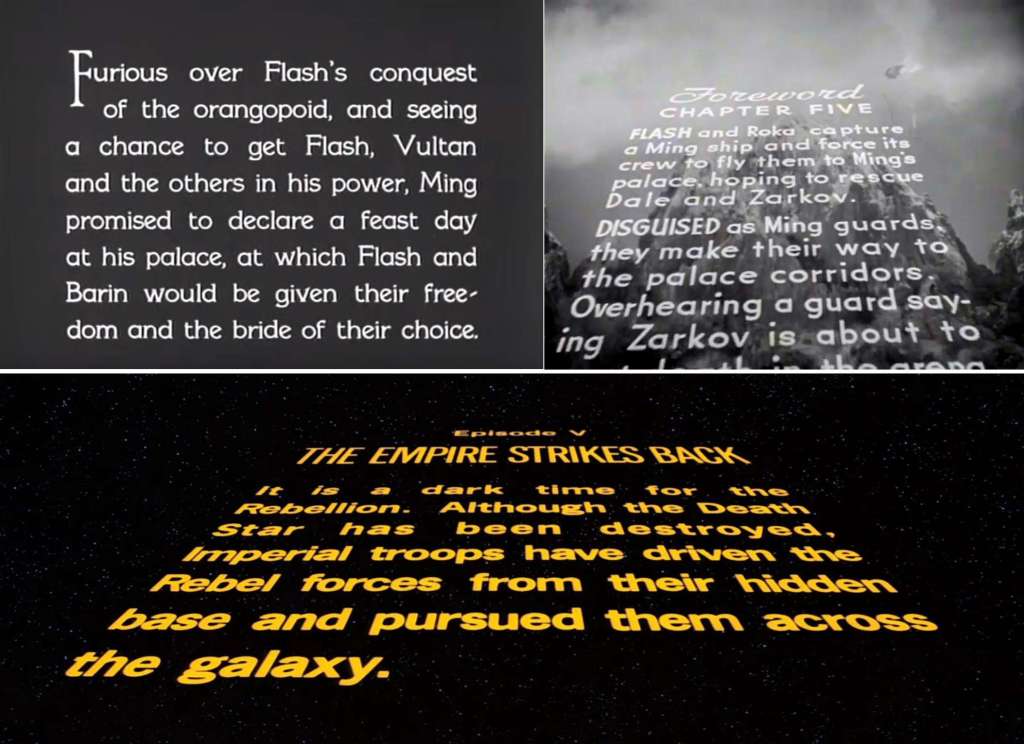

Flash Gordon (1936) was followed by Flash Gordon’s Trip to Mars in 1938 and Flash Gordon Conquers the Universe in 1940. Serial films were also not new at the time, dating back to the movie industry’s silent era. The Hazards of Helen was one of the longest: 119 episodes released from November 1914 through February 1917. Poor Helen, played by more than one actress because of the project’s length, had quite a troublesome life, burdened by such threats as runaway trains, runaway cars, and runaway horses. Flash Gordon took place over 13 weekly episodes, and each episode had a run-time of approximately 18-20 minutes. The entire production ran more than four hours – top that, Matt Reeves! Each episode began with a text-based summary of the previous episode, an idea that, by the time of Flash Gordon Conquers the Universe in 1940, evolved into the title crawl that Star Wars fans will recognize. That’s only one example of many influences the Flash Gordon serials had on contemporary science-fiction.

In many ways, the Flash Gordon movie was a generally faithful adaptation of the comic strips, first published in January, 1934, by Alex Raymond with help from ghost writer Don Moore. The strips were basically an attempt to exploit the success of the Buck Rogers comic strip that first appeared in 1929. (The Buck Rogers comic was an extension of two futuristic novellas written by Philip Francis Nowlan in 1928 and 1929, about the 25th century adventures of Anthony Rogers.) The Flash Gordon comic and film were swash-buckling, male fantasy entertainment, influenced as much by Jules Verne and H. G. Wells as by Robin Hood and Edgar Rice Burroughs (Tarzan of the Apes was published in 1912), all seen through a prism of American exceptionalism. In Flash Gordon, when the planet Mongo approaches dangerously close to the earth, dashing polo player Flash Gordon (Buster Crabbe) teams up with Dr. Zarkov (Frank Shannon) and Dale Arden (Jean Rogers) to travel to Mongo and confront its evil ruler, Ming (Charles B. Middleton). Originally intending to destroy the earth for no apparent reason, Ming has instead decided to conquer our planet. In their quest to defeat Ming, Flash and his allies encounter King Vultan and his hawkmen, Prince Thun and his lion men, Prince Barin and his…knights of the Round Table?…Ming’s henchmen in gladiator costumes, Ming’s wayward daughter Princess Aura (Priscilla Lawson), iguanas with rubber prosthetics, and various other characters. At its most basic level, Flash Gordon is about a hero who engages in physical brawls, flies around in a cool-looking spaceship, rescues a fair maiden, and stops the megomaniacal foreigner from taking over the world. This would remain the template for about a thousand other genre adventures, including the original Star Trek series.

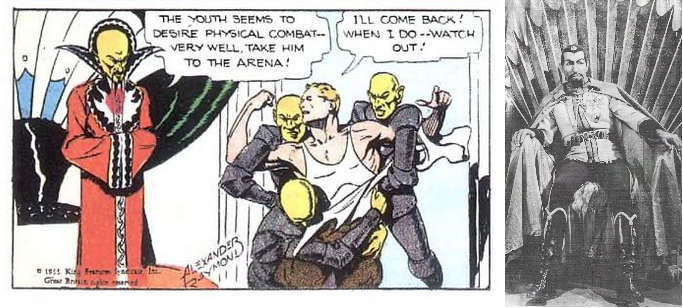

Thankfully, we’re spared origin stories for Flash, Ming, or any of the other characters. Flash’s entire origin story consists of parachuting out of a crashing plane and, by complete coincidence, landing near Zarkov’s laboratory just as the scientist is about to depart in his rocket. The primary nemesis in all three Flash Gordon movies, also like the comic, was Ming, emperor of the planet Mongo. Ming’s appearance, in the movie and the comic, adheres to an “Oriental” cliche that reflected the so-called “Yellow Peril,” a term that originated in the 1800s with Westerners’ fears of legal and hard-working Chinese immigrants in the U.S., Canada, and other countries. The character was derived primarily from Fu Manchu, the fictional Chinese villain created by British writer Sax Rohmer in 1912; Rohmer was influenced by U.S. lecturer and travel writer Bayard Taylor, who first traveled to China in the 1850s and wrote such horrific things about the Chinese that I won’t even repeat them here. In classic serial style, the first Fu Manchu book, The Mystery of Dr. Fu-Manchu, was a collection of short stories. (Fu Manchu was also the inspiration for Dr. No, the villain of Ian Fleming’s 1958 Bond novel. Neither Rohmer nor Fleming shied away from racial or ethnic cliches.) While Ming tries repeatedly to kill Flash and conquer the earth, one of his few weaknesses – true to most racial stereotypes – is an obsession with the white woman and Flash’s main squeeze, Dale Arden.

By 1936, however, one might expect U.S. audiences to have been more alert to the fascist expansionism of Hitler, Mussolini, and Franco (the Spanish Civil War began in 1936) than possible threats from Asia. European audiences certainly were, as indicated by a year-end British Pathé newsreel. Newsreels were a common information source from the 1910s until as recently as the 1970s. The Flash Gordon serial chapters were very likely preceded by a newsreel. Since Flash Gordon was produced by Universal Studios, the news may also have been from Universal, which distributed a twice-weekly newsreel from 1929 to 1967. A few of these are available at the Internet Archive. Did Ming represent an active threat in U.S. viewers’ minds? Judging from the available newsreels, it doesn’t appear so. Either way, Flash Gordon (the movie) is not overtly racist; the primary objective was entertainment, but the symbolism would have been plain enough to viewers who were looking for it. The bottom line: Ming is a vengeful, power-hungry sexual predator who betrays his own allies, is easily distracted by praise and flattery, and has a self-serving daughter of sketchy loyalty. Pure fantasy!

The premise, like all good soap operas, is to introduce a variety of characters with competing strategic and romantic objectives, put a series of obstacles in their way, and break the action up into discrete, easily-absorbed chapters. The plot – saving the earth from being conquered by Ming – is secondary to the characters’ shifting alliances and their diverse responses to outlandish threats. How much this particular soap opera holds your attention will depend a lot on your suspension of disbelief. The earth is never truly in danger and all of the heroes, along with most of the villains, will survive till the end; that is a great relief from the merciless body count of contemporary movies. It’s well established that George Lucas, Steven Spielberg, and others were inspired by Flash Gordon and other such serials, and it’s fun identifying some of those influences. The chapters are short enough to keep the action moving. I personally find Flash Gordon a great romp. The episodes were combined and heavily edited into a 72-minute film released in the U.S. in 1949 under the title Rocket Ship. Shifting attention spans aside, I recommend the full experience because that’s how it was intended to be seen. Flash Gordon occasionally shows up on various streaming services and can often be found on YouTube. And many of the Flash Gordon comic strips can be viewed at the Internet Archive.

But, wait, we haven’t addressed the greatest threats of all: wooden acting and flimsy production design! How will audiences endure such low-budget productions? Why do all these aliens look so human? Is there really life on Mars? And will Dale Arden ever stop fainting? Tune in next time for Chapter 2: Keep Your Hands Off My Outdated VFX; or, Flash Gordon’s Trip to Mars.

Leave a comment