“Do we ever know as deeply as we know in childhood? Does adult life amount to anything more than a futile attempt to invalidate the deepest truths we know about ourselves and our world?”

—Nobody’s Fool by Richard Russo–

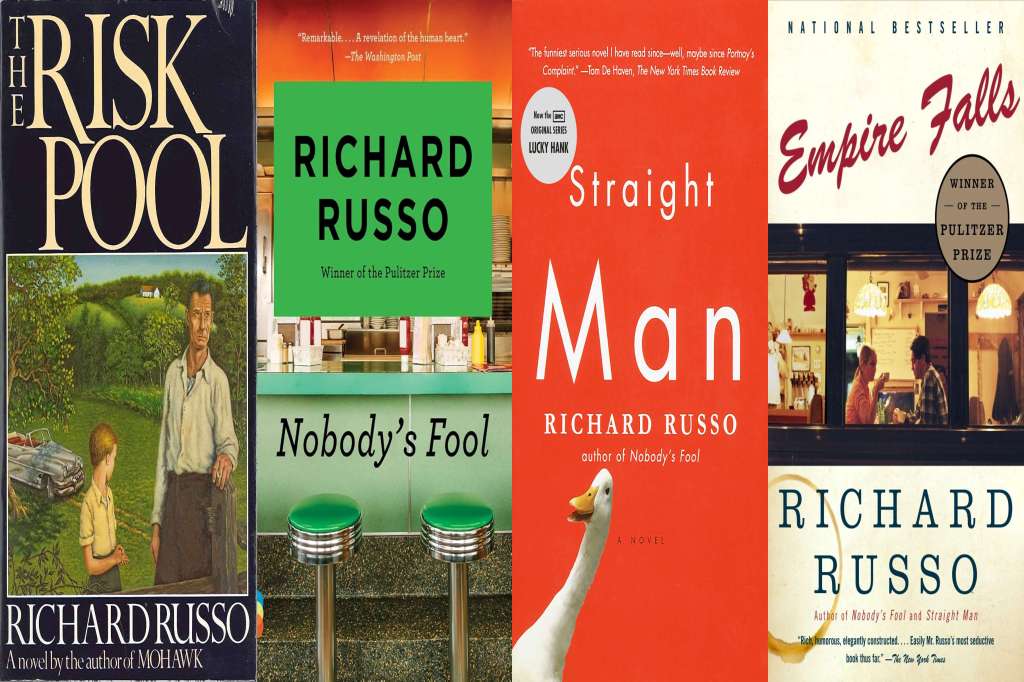

My grandmother’s funeral introduced me to the joy of Richard Russo‘s writing. I’m an avid reader, but somehow I missed Russo’s first five novels, published between 1986 and 2001. When my grandmother passed away in 2003, she was laid to rest in Indiana, not far from my hometown. I lived in North Carolina in those days and had only returned to my birthplace once during the previous 14 years. Despite the sadness of the occasion, I made time for a brief hometown nostalgia tour, including the comic and used book store that had been a haven for me as a teenager, my source for Spider-Man comics and vintage James Bond paperbacks, among other things. In a town oriented around jocks, that book store was one of the few home court advantages available to me. I was thrilled to see that a small town could still support such a business nearly twenty years later. By extreme good fortune, they had a softcover copy of Russo’s 1997 book Straight Man; one impulse purchase later and I was hooked. I’ve read all of Russo’s novels, after recently finishing 2023’s Somebody’s Fool, a book that completes a trilogy with Nobody’s Fool (1993) and Everybody’s Fool (2016), set in the fictional New York town of North Bath.

Straight Man is a bit of an anomaly in Russo’s published works, set in an academic environment with an English professor protagonist, while most of his books lean more blue collar. But the decline of American small towns, subject to the commoditization and off-shore labor exporting of capitalism, is always present. (I’m still surprised that my hometown survived after the closing of a Chrysler factory that was one of their primary employers for decades.) Another common thread is the challenge of cornering one’s true identity in an obstacle course of career struggles, generational conflict, the burden of expectations (from oneself and others), and emotional scars given and received. One of Russo’s skills is the ability to create entire communities populated by fully-realized characters who connect and bounce off one another exactly the way real people often do. The plots meander rather than following a defined path, also like real life. This is probably why there have been so few screen adaptations of these books. A film version of Nobody’s Fool was directed by Robert Benton; time constraints forced a lot of characters and relationships to be trimmed or eliminated, but it was still a very good movie. HBO aired an excellent 3+ hour miniseries of Empire Falls in 2005. Both productions had brilliant casts that included Paul Newman and Philip Seymour Hoffman.

“She looked over at me in the semidark with the same scared look she’d had as a girl learning to drive. ‘Do you ever feel like you’re nobody at all?’

“’No,’ I admitted. ‘There are times when I feel like I’m somebody I don’t like very much.’”

—The Risk Pool by Richard Russo–

Much of the action in the books revolves around characters in the middle, often grown sons who are also fathers. In Nobody’s Fool, Peter Sullivan’s divorce separates his children while loss of a job – failure to achieve tenure at the university where he taught – drives him back to his hometown and his estranged father. In Straight Man, Hank Devereaux Jr.’s daughter is in a troubled marriage at the same time his own long-lost father returns. In Empire Falls, Miles Roby’s daughter Tick struggles in high school while Miles’ errant father keeps hitting him up for beer money. Even death can’t terminate this middle status, as Jack Griffin carries his father’s cremains in the trunk of his car in That Old Cape Magic. There is a lot of estrangement in Russo’s fictional families, because families have a lot of strangeness. Some of these people seem to wonder how they ended up related to one another. I understand that feeling, what with being the black sheep of my own family as long as I can remember.

This is the tip of the iceberg of the various conflicts that drive Richard Russo’s stories. But much of it – again, like life – involves individuals who have caused harm to others or have been harmed by them. The damage is sometimes accidental, and other times a result of lashing out in emotional confusion. A process of self-reflection, and contemplation of others, often leads to varying degrees of forgiveness by the final page. I hadn’t truly considered how essential forgiveness is throughout these stories until I reached the end of Somebody’s Fool. Russo shifts point of view from chapter to chapter so the reader gets a front-row seat to the characters’ thought processes. Late in the book (SPOILERS AHEAD!), after Peter and his troubled son Thomas (named after the Bible’s doubting Thomas, perhaps?) have both behaved in generally unforgivable ways, they somehow establish a truce and a plan to get to know each other. There are no guarantees, the relationship may still go south, but they’ve committed to make the effort. It’s easy to see how both of their lives will be better for the attempt.

“It’s not an easy time for any parent, this moment when the realization dawns that you’ve given birth to something that will never see things the way you do, despite the fact that it’s your living legacy, that it bears your name.”

—Straight Man by Richard Russo–

In The Risk Pool, Nobody’s Fool, and Empire Falls, much of the forgiveness is most needed by wayward fathers who are oblivious the harm they’ve caused. They struggle the least with guilt and, as a result, are the most impervious to criticism or insult. Sometimes the foundation of a personality is plainly visible. The Risk Pool spells out from page one why Ned Hall’s father Sam is so “rockheaded”: the trauma of serving in World War II. Other times, the reasons are hazy, difficult or impossible to identify, or simply unknown because they happened a long time ago to other people, and involve a past that no one much wants to revisit. My parents were so emotionally distant that I often felt abandoned. I don’t know the cause, but I can guess that it had lot to do with their own parents and the cold reality of being born into 1940s rural America. Even more inexplicable is how I could have started out with my parents’ DNA but strayed farther from them with every passing year. I see no clear answer for their support of fascist ideology while I’ve progressed into the outskirts of socialism. Maybe it was all those Star Trek reruns I watched. Or maybe I grew up in the sweet spot of U.S. public education, when teachers weren’t run ragged every day and books were read more often than they were banned.

Fiction, of course, is never perfectly aligned with real life. In the novels, most of the characters who need to generally make peace with one another. It’s not an easy process, but it’s possible because they acknowledge their own shortcomings and the redeeming qualities of others. In Somebody’s Fool, Ruth and Janey, mother and daughter, reach a kind of reconciliation specifically because they go through the hard work of reflecting both on themselves and each other. It doesn’t hurt that troublesome parents sometimes end up being outstanding grandparents, as Ruth demonstrates with Janey’s daughter Tina. And Donald “Sully” Sullivan does the same with his grandson Will in Nobody’s Fool and Everybody’s Fool. My own grandparents were always very kind to me; I never asked, but I doubt they were so easy raising their own children, who became my parents, and my aunts and uncles. My parents continued the pattern: I wasn’t considerate enough to give them grandchildren, thereby protecting myself from the generational middle ground, so they went out and found some in other families. I barely recognized them as they unleashed an avalanche of affection on other people’s children.

“It always amazed me how little he understood what I was feeling. It meant, among other things, that my understanding of him probably wasn’t much better.”

—The Risk Pool by Richard Russo–

Forgiveness in literature is guided by the author, which doesn’t diminish these important fictional examples of letting go of the past. But what about real life, when few people are willing to tackle difficult self-reflection? In Somebody’s Fool, Peter says the magic words – I’m sorry – that we hear so rarely in reality. How do we forgive people who not only don’t care about being forgiven, but don’t even realize they did anything requiring forgiveness? Because the truth is, I haven’t reached the point that Russo’s characters have, despite decades of reflection. I’m not sure I ever will. How many times did my father raise his hand as if he intended to strike me? At the same time, my parents introduced me to the public library, a wondrous source of comfort and happiness throughout my life. They helped finance my college education. Does that justify forgiveness of a parent who threatened violence and still deems himself above reproach? What magnitude of positive acts balance out the negative? After all, a lot of kids suffer a lot worse than I did. I remember that every time I look at a photo of my grandparents and their children on their Indiana farm in 1946. Truly horrific outcomes waited for a couple of those kids, tragedies that no family is prepared to cope with. By that measure, my father and I were both among the lucky ones. Still, did his parents intimidate him the way he went on to intimidate me? Or worse? Did tragedy make them more compassionate parents, or did it turn them cruel? Did it do the same to my father? I’ve spent a lot of time with these thoughts, but still, as The Chicks sang, I’m not ready to make nice.

And never mind my personal life. How do we forgive today’s rampaging fundamentalists who are deliberately, aggressively, making the world unlivable for increasing numbers of humans? People who find joy in the suffering of others? How do we forgive past behavior when new pain is inflicted daily? Maybe there comes a time when fear and anger are the very qualities we need in order to survive. Like so much of 21st century life, there is no visible end point, just chaos and darkness. If there’s an answer, I don’t have it, but my response is to continue seeking good stories, absorbing as many as I can until the lessons stick: nonfiction stories, to stay grounded in the outlandish reality of human behavior, and fictional stories, for insight into theoretical realms of possibility. Which brings me full circle back to my advice to read Richard Russo’s books. How does Russo write with such empathy? One reason might be his own path to forgiveness of his absentee father, who was apparently a model for both Sam Hall in The Risk Pool and Sully in the North Bath books. Real life influences fiction, so the rest of us can apply fiction’s parables to reality. And if the parents stir up bad memories, I can always count on the grandparents for better ones.

Back in 2003, while I attended my grandmother’s funeral and came across that copy of Straight Man, Hurricane Isabel made landfall on North Carolina’s Outer Banks as a Category 2 storm. My central North Carolina home wasn’t damaged, but the county suffered enough to be on FEMA’s public and individual assistance map. The irony was clear: the weather had always been one of my grandmother’s favorite conversation topics. Really, you have no idea how much time one person can spend talking about the weather. Discussing the daily forecast was a reliable comfort whenever I visited in her later years. Now it was as if, in death, she was still watching the forecast and had somehow arranged to take me out of harm’s way. The day of her funeral was even stranger. The September day started out unseasonably sunny and warm. During the funeral, at the exact time we drove from the funeral home to the cemetery, an abrupt cold front rushed through. I couldn’t help but laugh as we all sat by the gravesite, shivering and keeping wary eyes on dark, turbulent clouds. I’ve never been so amused by unpleasant weather. Grandma would have loved that.

Leave a comment