This essay is part of a series exploring movies that are problematic but popular. Title suggestions are welcome in the comments or via the Contact Me page. If you enjoy this, please share it on your favorite social media platform so others can discover my work.

“The jet is so fast, it races the sun. This is what has happened

since the big jets came. Time has been annihilated.”

–Narrator, Boeing Boeing (1965)–

Imagine a U.S. film adaptation of a French play, featuring two of the past decade’s biggest stars, with a director who would soon change the face of television, and promoting the sly message that corporate capitalism will ultimately put the individual entrepreneur out of business. That basically sums up the 1965 comedy of errors Boeing Boeing. It’s also a fairly underhanded way of describing what is really a sex farce about a man trying to maintain phony romantic engagements to three different women simultaneously. Boeing Boeing was hardly a massive box-office success, but it ranked about 36th in actual North American revenues for 1965. (The Sound of Music was number one.) Quentin Tarantino thought enough of Boeing Boeing to include it in his first film festival in Austin, Texas, in 1996.

Boeing-Boeing was the best known work by French playwright Marc Camoletti. There doesn’t seem to be much published about the play’s debut in 1960, but the English-language adaptation was first performed at London’s Apollo Theatre in 1962; in 1965, the production moved to the Duchess Theatre and ran for another four years. Boeing-Boeing opened on Broadway in 1965 and has been the subject of numerous revivals over the years. In 1991, Boeing-Boeing was declared the most performed French play in the world. In the stage version, the protagonist is French architect Bernard, who maintains three flight attendant fiancees in his Paris flat. Through careful coordination of the flight attendants’ schedules, and with the help of Bernard’s weary maid Berthe, each is kept in the dark about the others. A faster Boeing jet throws Bernard’s schedule into chaos. A further complication is the arrival of Bernard’s American friendly rival Robert, who expects a share of the action in exchange for not sharing Bernard’s secrets.

“They’ve been tried and tested. You know, the entrance exam to these major airlines is very difficult. They have to be healthy, good at cooking, witty, friendly.”

–Bernard, Boeing Boeing—

As a U.S. production, the film adaptation changes Bernard to a U.S. journalist based in Paris. Berthe becomes Bertha. The flight attendant nationalities are revised from French, German, and American, to French, German, and British. As presented in the film, Bernard is a free-wheeling American individualist applying the planning and time-management techniques of Organization Man to his illegitimate personal life. Most of the action takes place in Bernard’s Paris apartment. He deliberately chose flight attendants because their professional qualifications overlap with his own criteria for romantic partners. Bernard seems disinterested in his three fiancees as individuals and more interested in maintaining three engagements simply because he can. And it’s the film’s treatment of women that makes Boeing Boeing a movie we probably shouldn’t love, despite its current 3.2 rating on Letterboxd.

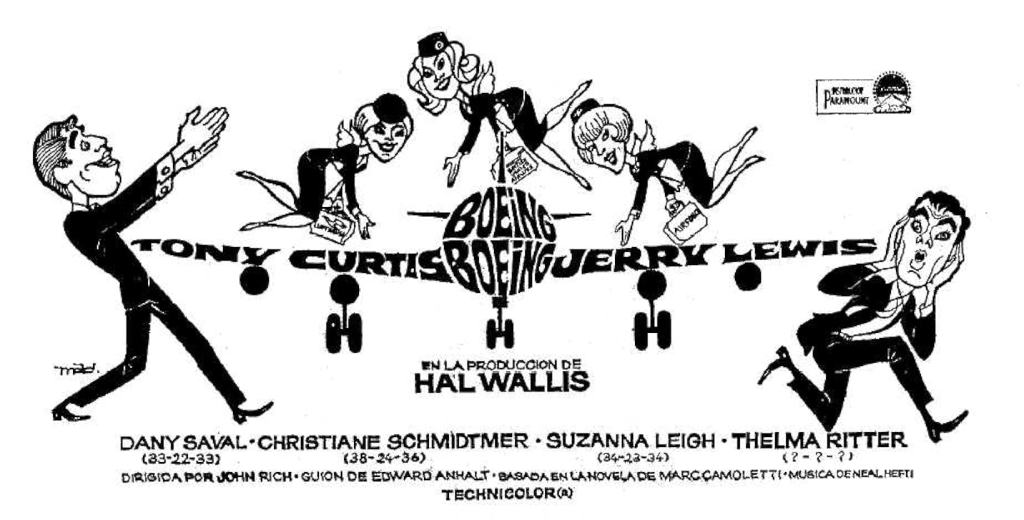

The flight attendant roles are performed by Dany Saval (Air France), Christiane Schmidtmer (Lufthansa), and Suzanna Leigh (British United). We’re introduced to the trio in the opening credits with not just their photos, but their measurements! Why, that’s just…ahem…data for Organization Man to…process and collate and…whatever. It’s small consolation that the movie doesn’t reduce the women to a set of numbers, but instead to two-dimensional personalities defined by cultural cliches: for example, for breakfast, Miss Air France expects souffle, Miss Lufthansa wants sausages and sauerkraut, and Miss British United demands kidneys. Constant shuffling of the breakfast menu is one of housekeeper Bertha’s tasks that becomes more complicated as the three women converge on Paris at the same time.

“Who said anything about wives? They’re fiancees, and that’s the way

they’re going to stay. That way I have all the advantages of married life,

without any of its inconveniences.”

–Bernard, Boeing Boeing—

Most of the male characters’ (more on them shortly) attitude toward the women is sexist but typical of movies of that era – they see women as part of a self-oriented landscape, not as individuals with their own desires and plans. The movie doesn’t endorse polygamy, thankfully, as Bernard has no plans to marry and the two men ultimately end up alone, in search of their next conquest. But clearly Bernard is okay with what amounts to a polyamorous lifestyle, which wouldn’t be so disturbing if the women were in on the game. Even worse, Miss Lufthansa, the most athletic of the flight attendants, is drugged to keep her out of sight of the other women. The imagery of Bernard and Bertha dragging around a helpless Miss Lufthansa doesn’t hold up well these days. So while Boeing Boeing doesn’t stray into misogyny, it’s highly sexist.

The movie might also be offensive to the very Organization Men whose tactics Bernard borrows to manage his highly sensitive timeline. Bernard is the Organization Man gone astray, serving his own tawdry ends and not the Establishment. In 1965, the ultimate ’60s Organization Man, Robert McNamara, was applying operational efficiency to the administration of the Vietnam War: 1964 – 1965 were years of dramatic escalation of U.S. involvement in Vietnam. (It may or may not be ironic that, like Boeing Boeing, the Vietnam War also started out as a French production.) And McNamara may have relied on IBM computers in his planning, as IBM controlled 65% of the still-young computer market in 1965. Despite President Johnson’s plan for a Great Society that would better recognize the working classes, by the mid-1960s union influence was already in decline, U.S. manufacturing jobs were in the early stages of being outsourced to other countries, and corporate conglomerates were on the rise.

“Air travel at that time was something special.

It was luxurious, it was smooth, it was fast.”

–Aviation historian Graham M. Simons on 1950s – 1970s air travel, CNN, 5 August 2022–

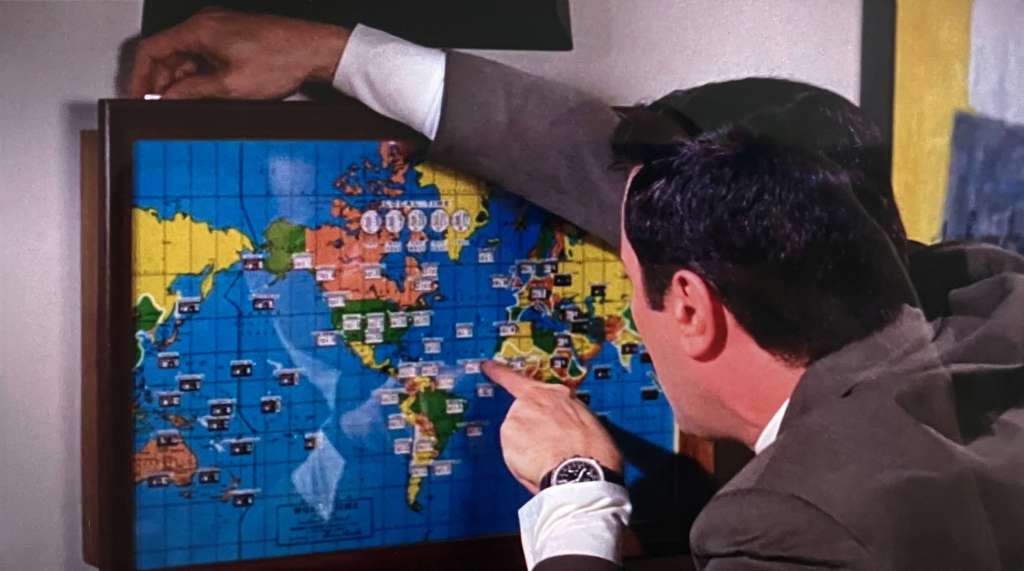

Corporate influence is reflected in Bernard’s true nemesis, technological progress: the higher-powered jet engines that will have the flight attendants zooming around the world faster than Bernard can keep up. British United is about to acquire a Vickers VC10: “It’s got four magnificent engines that develop 20,000 pounds of thrust each.” Miss Lufthansa is being transferred to “the new intercontinental jet. It’s a super-Boeing with a cruising speed of Mach 0.88. … Four Rolls-Royce jets each with 21,000 pounds of thrust.” This “super-Boeing” sounds like the original Boeing 737, which did enter service with Lufthansa but not until 1968. (The never-produced Boeing 2707 was planned as a Mach 3 jet intended to compete with the Concorde, which entered prototype production in early 1965.) And Miss Air France will soon be working on a new “ultra Caravelle” jet. This is probably Sud Aviation’s Caravelle 10B, sometimes known as the Super Caravelle. The French Caravelle jetliner was developed in the early 1950s, but the 10B, with newer engines and an expanded passenger capacity of 105, first flew in August, 1964. Photos of biplanes in Bernard’s apartment emphasize a shrinking world in the face of continuous technological advances.

Decades later, the movie also reminds us how much more pleasant air travel used to be. Bernard’s entire existence is based on the reliable schedules of multiple airlines. All of this technological progress didn’t help us passengers much in the long run. British United doesn’t even exist today, having merged with Caledonian Airways in 1970 to form British Caledonian, which was then conscripted into British Airways in 1988. It’s hard to imagine Bernard getting involved with a flight attendant from any of the contemporary U.S.-based air carriers; their widespread delays and flight cancellations would make a consistent schedule virtually impossible. But in the 1960s, air passengers had more legroom, airline employees were less overworked, and there was not a social media influencer in sight. And as for Boeing, which is hardly mentioned but always present as the movie’s namesake, the company had a far different reputation in the 1960s, when it introduced such historic aircraft as the 727 and 737 and was contracted to manufacture the first stage of the Saturn V rocket that would take us to the moon. Bernard even consults a printed comprehensive airline schedule, because such a thing was practical in those days. OAG (Official Airline Guide) was established in 1929 as a central database of airline schedules, routes, airline codes, and other useful information for travelers. OAG still publishes a Pocket Flight Guide, which hardly seems pocket-sized with “165,000 direct and connecting flights.” One risk of nostalgia is that it exposes how much we haven’t accomplished since the good old days.

“I understand it from your point of view. But what do the girls get out of it?”

–Robert, Boeing Boeing—

Ultimately, Boeing Boeing succeeds or fails based on the chemistry between the two leads: Tony Curtis as Bernard and Jerry Lewis as competing journalist Robert. Both charismatic actors were still in their prime, though their finest roles were, for the most part, behind them. Lewis was probably the biggest surprise to audiences at the time. He had long since split from Dean Martin by this time, and a 1959 contract with Paramount made Lewis the highest paid actor in Hollywood and gave him considerable creative control over his work. He was still fresh from box office successes like Cinderfella (1960), The Nutty Professor (1963), and The Patsy (1964). He guest-hosted The Tonight Show in 1962 during the interim between hosts Jack Paar and Johnny Carson, and Lewis got even better ratings than Paar had. Lewis’ performance would have been something of a shock to movie-goers: TV audiences had seen the “real” Jerry Lewis (on The Tonight Show, for example), and his Jekyll-and-Hyde role in The Nutty Professor had offered a preview, but Boeing Boeing was the first film where Lewis essentially played himself rather than the manic man-child character for which he was best known.

Like Lewis, Tony Curtis had performed in beloved films over the past decade, playing diverse characters in Sweet Smell of Success (1957), The Defiant Ones (1958), Some Like It Hot (1959), and Spartacus (1960). An early career focus on dramas led to a series of romantic comedies in the 1960s – including Boeing Boeing – that seemed to lead to a downturn in Curtis’ popularity, in movies like Wild and Wonderful (1964), Goodbye Charlie (1964), and Not with My Wife, You Don’t! (1966). Curtis seemed to genuinely admire Lewis – Lewis had attended Curtis’ 1951 marriage to Janet Leigh – but a professional rivalry between the actors is reflected in the placement of their names on the poster, in the shape of an airplane propeller, to emphasize equal billing. The opening credits were similarly designed, with the two names spinning around the front of a jet engine. The production was also troubled by Lewis’ status with Paramount; despite the 1959 contract, Lewis’ box office had been declining and in 1966 Paramount was acquired by Gulf + Western. Lewis held up filming by leaving the set multiple times without warning. Boeing Boeing ended up being his last film with Paramount, the studio where he had launched his career alongside Dean Martin in 1949.

The final member of the primary cast was Thelma Ritter as the constantly burdened housekeeper Bertha. Ritter had a long list of film credits, with a particular emphasis on supporting roles as working-class characters, having appeared in such movies as All About Eve (1950), Rear Window (1954), and The Misfits (1961). Boeing Boeing was late in Ritter’s career and she appears nearly as weary as the character she plays, responding to a revolving door of barked breakfast orders and shuffling the flight attendants’ clothing from one bedroom to another. “It’s not easy, you know,” is her mantra throughout the movie. Bertha also symbolizes the close alliance between the U.S. and France, and all of western Europe, that existed at the time. Bertha tells us she has a French work permit after being honorably discharged from the U.S. Army, where she was chauffeur for General John J. Pershing, commander of American Expeditionary Forces during World War I. This dates Bertha, but also reminds us that France had been ravaged by two world wars within 50 years of Boeing Boeing‘s release and that the modern world was geopolitically linked whether it wanted to be or not. Ritter appeared in only two more movies after this, and her final professional appearance was on a 1968 episode of The Jerry Lewis Show.

Finally, director John Rich had directed a few motion pictures by 1965, including Elvis Presley’s Roustabout (1964), and he would later direct another Elvis movie, Easy Come, Easy Go (1967), he was best known for his extensive television work both before and after Boeing Boeing. Rich directed 27 episodes of Our Miss Brooks, 41 episodes of The Dick Van Dyke Show, and 26 episodes of Gomer Pyle – USMC, among many others. Rich’s biggest claim to fame probably resulted from his decision to turn down directing the premiere episode of The Mary Tyler Moore Show to instead direct the debut episode of All in the Family. Rich ended up directing 81 episodes of All in the Family, including the iconic Sammy Davis Jr. episode. Later, Rich teamed up with Henry Winkler to form the cleverly named Henry Winkler / John Rich Productions, the company that produced MacGyver for Paramount Television. For a movie that plays like an elitist version of The Odd Couple, Rich was the perfect director for Boeing Boeing.

“…our present policy can lead only to disastrous defeat…”

–Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara and National Security Advisor McGeorge Bundy, July 1965 memo to President Lyndon Johnson–

The considerable talent behind Boeing Boeing makes it an entirely American production. Instead of the cultural contrast between French Bernard and American Robert in the play, in making both men American, the movie settles for easy European stereotypes clashing against the relentless American quest for more. (“I thought of you only as an American,” Miss Lufthansa tells Robert. “You know, a machine for making money.”) In the end, we’re left with the impression that the three women will be just fine, and a little wiser. Bernard and Robert, on the other hand, find themselves in limbo, alone together, and this is clearly not the first time: twice during the film Bernard harks back to shared adventures in Casablanca and Suez, Egypt: “Remember the time you covered that Suez thing, you had these four dames…?” In this latest venture, Bernard’s entrepreneurial spirit is no match for the advance of aviation technology. It should be no surprise that, while Bernard and Robert plot their next conquest in the final scene, a woman is at the steering wheel.

Maybe we should be grateful that Bernard’s version of Organization Man limits his logic and efficiency to his personal life. In 1963, Robert McNamara had predicted that, by 1965, the Vietcong insurgency would be controlled and most U.S. military advisors would come home. In reality, in July 1965, only five months before Boeing Boeing‘s release, McNamara increased the draft call for U.S. soldiers from 17,000 / month to 35,000 / month. Bernard would understand that when the French finally bailed out of Indochina, the U.S. should have left well enough alone. Boeing Boeing may only be a light comedy, but the lesson is ultimately the same: reducing human affairs – whether romantic or geopolitical – to simple operational calculations is no way to win hearts and minds.

Leave a comment