“Politicians, ugly buildings and whores all get respectable if they last long enough.”

John Huston as Noah Cross, Chinatown (1974)

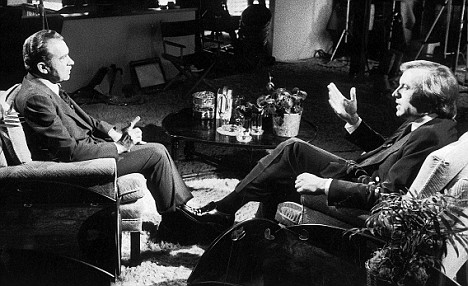

Noah Cross knew what he was talking about. Consider Richard Nixon, who seemed washed-up as a politician when he lost the California governor’s election in 1962. “This is my last press conference,” Nixon spitefully told reporters the day after the election. If only. Yet in 1968 he was elected president. By 1974, Nixon was ruined again and on a bigger scale, resigning the presidency to avoid the consequences of Watergate. A series of 1977 interviews with British TV host David Frost began Nixon’s second comeback and his elevation to the status of elder statesman, publishing a series of policy books throughout the 1980s and early 1990s.

As for ugly buildings, read this passage from the “Artists Against the Eiffel Tower” petition of 1887: “We, writers, painters, sculptors, architects and passionate devotees of the hitherto untouched beauty of Paris, protest with all our strength, with all our indignation in the name of slighted French taste, against the erection … of this useless and monstrous Eiffel Tower… …we shall see stretching like a blot of ink the hateful shadow of the hateful column of bolted sheet metal.” Some may still find the Eiffel Tower offensive, but they clearly hold a minority opinion. Frank Lloyd Wright‘s design for the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York City has undergone a similar, if less dramatic, revisioning; originally given such labels as “washing machine” and “bee hive,” the museum today seems an organic element of the Manhattan skyline.

And now I’m thinking about how this sentiment applies to pop culture. I re-watched the 2008 Bond movie Quantum of Solace last week. You’re probably already rolling your eyes – either because you’re not a Bond fan, or because you are a fan and haven’t bothered with QoS since your initial viewing. I understand. I was disappointed the first time, also. QoS seemed like a big step down from Casino Royale (2006), which launched Daniel Craig‘s Bond on such an impressive trajectory.

Somehow, seventeen years has passed since the movie’s release, and my assessment of QoS has improved more than a quantum in that time. Despite some incomprehensibly edited action sequences and the bizarre choice to depict M in an overly domestic context, among other missteps, QoS has a lot to offer. The story anticipates what is gradually becoming a potable water crisis throughout the world. The respectful collaboration between Bond and Camille (Olga Kurylenko) is the heart of the story: like Melina (Carole Bouquet) in For Your Eyes Only (1981), Camille seeks vengeance, but she is partnered with a different Bond for a different era. Instead of advising that “Before setting off on revenge, you first dig two graves,” this time Bond assists Camille because he also seeks vengeance for Vesper’s death in Casino Royale. In addition, the touching camaraderie between Bond and Mathis (Giancarlo Giannini), Bond’s equivocation between his personal grief and loyalty to his country, Mathieu Amalric‘s fiendish performance as Dominic Greene, one of the underrated villains of the franchise, and Roberto Schaefer‘s cinematography – all of these elements make for a more substantial movie than most of us believed at the time. History has granted respectability.

To be sure, nostalgia can influence such assessments. I appreciate the Star Trek series Deep Space Nine, Voyager, and Enterprise more now than when they originally aired. That’s not just a result of my own (hopefully) advanced wisdom into the series’ acting, storytelling, and production values, but also a yearning for the pre-2009 period that I consider “classic” Star Trek. Nostalgia might also be a factor in my revised attitude toward QoS – it is now one of the 25 “true” Bond movies before the forces of evil hijacked the franchise. I’ll be hard-pressed to grant respectability to any future cinematic Bonds.

Sometimes, history can have the opposite effect. As a young, burgeoning movie fan, I considered Gone with the Wind (1939) one of the greatest movies ever made. And though I still appreciate the film’s acting talent and epic scale, the story’s dependence on white supremacy and nostalgia – there’s that word again – not to mention the infamous rape scene, are painfully obvious to me. Returning to the Bond franchise, even though I still enjoy Ian Fleming‘s original novels, I also have a better appreciation of how problematic those books can be. A recent re-read of Goldfinger, published in 1959, had me cringing at Bond’s crude and misogynistic reflections on why giving women the right to vote was a mistake.

More often than not, however, such historic reassessments seem to turn out more favorably. Along with QoS, I also watched the 2003 anthology film Coffee and Cigarettes, written and directed by Jim Jarmusch. This is the kind of movie I wouldn’t have even bothered with in my younger years. I don’t smoke and I’m allergic to coffee, so what’s the point? Now, however, I’m more interested in what Jarmusch has to express, even though I may not always know how to interpret it. And this, again, is partly a result of my own maturation, but also a testament to the film’s durability – the personal nature of the movie’s short stories combined with black and white cinematography give the work a timeless quality. Collectively, it’s also easier to hold such movies in higher regard because Jarmusch continues to build an impressive body of work. Those early films weren’t luck, but the work of a creative writer/director who refused to compromise to the commercial interests of studios.

I’ve long since lost track of how many Wikipedia pages I’ve read about films that turned off contemporary critics or audiences, only to gain a better reception over time. The Night of the Hunter (1955), the only movie directed by Charles Laughton, didn’t get much appreciation when it was released. The trade journal Harrison’s Reports called it a “choppily-edited, foggy melodrama.” Opinions started changing in the 1970s, and many now regard it as a classic. Critic Dave Kehr called The Night of the Hunter “an enduring masterpiece”; Spike Lee and the Coen Brothers have referenced it in their own work.

Similarly, some movies considered classics today didn’t necessarily have movie-goers lined up around the block upon initial release: It’s a Wonderful Life (1946), The Thing (1982), The Princess Bride (1987) (“a modest success”), The Shawshank Redemption (1994), and Office Space (1999) all had poor to middling box office results before gradually attaining beloved status among a wider audience.

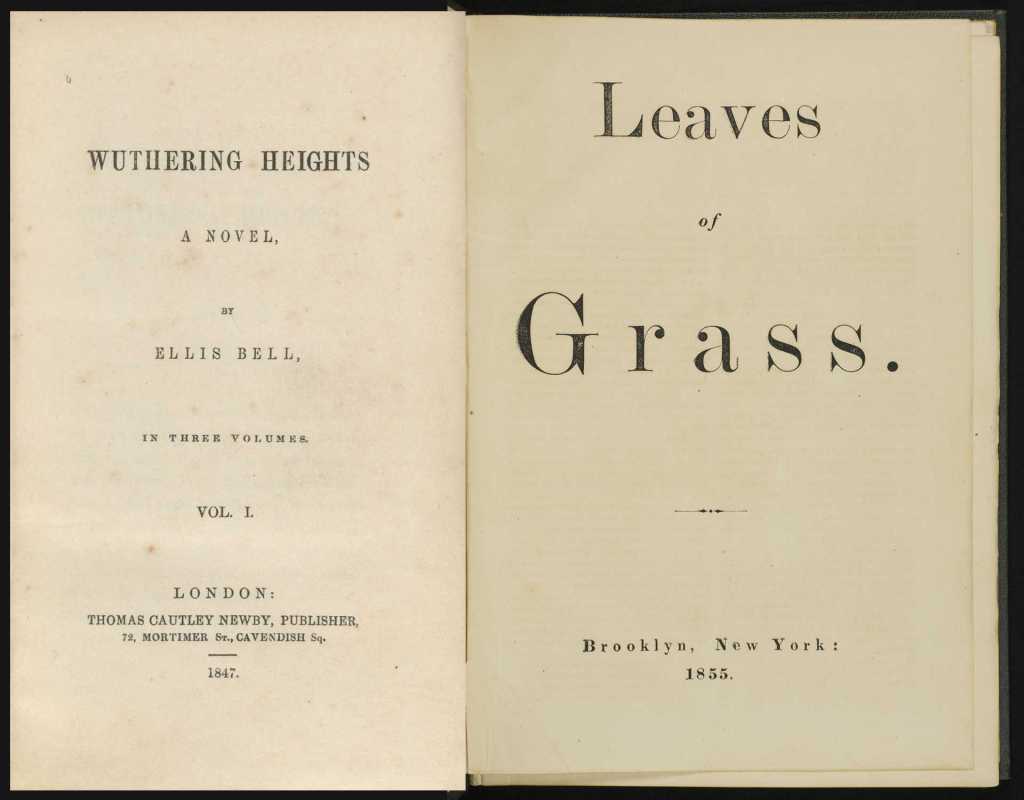

This doesn’t just apply to movies. Vincent Van Gogh received some critical acclaim during his life, but even his own beloved brother didn’t sell Vincent’s paintings. When Walt Whitman published Leaves of Grass, the U.S. Secretary of the Interior found the collection so offensive, he fired Whitman from his Department of the Interior job. The Saturday Press cruelly suggested Whitman consider suicide. And critics seemed mystified by Emily Brontë‘s Wuthering Heights when it was published in 1847. Graham’s Magazine called it “a compound of vulgar depravity and unnatural horrors.” Despite admitting being spellbound, The Literary World criticized “the disgusting coarseness of much of the dialogue, and the improbabilities of much of the plot.”

Time changes us all, individually and collectively. History allows us perspective and context, and frees us from the transient emotions of the present moment. While I sometimes appreciate rankings and “best of” lists, they are fleeting estimations of the moment, not anything that will endure. In the Sight and Sound 2022 Directors’ Poll of great movies, Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975) was ranked #4 and In the Mood for Love (2000) was #9. Neither film appeared on the same survey in 2012. Did they suddenly become great movies? Did the extra ten years allow more time to reflect and place those films in a broader context? Or was the later list influenced by “political correctness,” as claimed by a handful of right-wing-leaning industry insiders?

In the grand scheme, maybe it doesn’t much matter. If there is a point, maybe it’s that we shouldn’t become too attached to a movie, book, painting, or building as anything more than what it is. Just because we rejected something yesterday doesn’t mean we need to keep rejecting it. Conversely, assigning a label of “great” or “classic” to a work implies that the rest of us have some obligation to appreciate it, which gets into canon, curriculum, and representation, all bigger issues for another day. For today, maybe it’s enough to enjoy what we enjoy, to allow ourselves the insight of time to revisit past perceptions, and to keep sharing our favorites among ourselves.

And, in the meantime, consider giving Quantum of Solace another try. Trust me.

Leave a comment