This essay is part of a series exploring movies that are problematic but popular. Title suggestions are welcome in the comments or via the Contact Me page. If you enjoy this, please share it on your favorite social media platform to help other readers discover my work.

“A man, gentle, unafraid in the face of danger, courteous always without condescension or servility, tactful, honorable in all his relations with mankind, patriotic, subordinate, an example to all about him of initiative, ambition, loyalty, good judgment, justice, and kindness; such a one fulfills in its highest sense, the true meaning of the phrase, ‘An Officer and a Gentleman.’”

—The True Meaning of the Phrase “An Officer and a Gentleman”, Lt. (j.g.) H.E. Dow, 1922–

It’s funny how different aspects of a book or movie will register with us at different stages of life. I wrote a bit about this in November, but the thought came to me again while re-watching An Officer and a Gentleman, the 1982 box office smash directed by Taylor Hackford. (Hackford also directed one of my favorite good vs. evil morality tales, The Devil’s Advocate (1997).) Some moments in An Officer and a Gentleman practically hit me over the head this time, moments I had barely even noticed during previous viewings, which, in fairness, were well over ten years ago. In hindsight, the movie seems like the perfect advertisement for Reagan’s America, in which there is only one right team, and our choice is to join that team or be left behind. Despite this, I confess, I get goosebumps at all the intended moments and find the film highly entertaining. But should I?

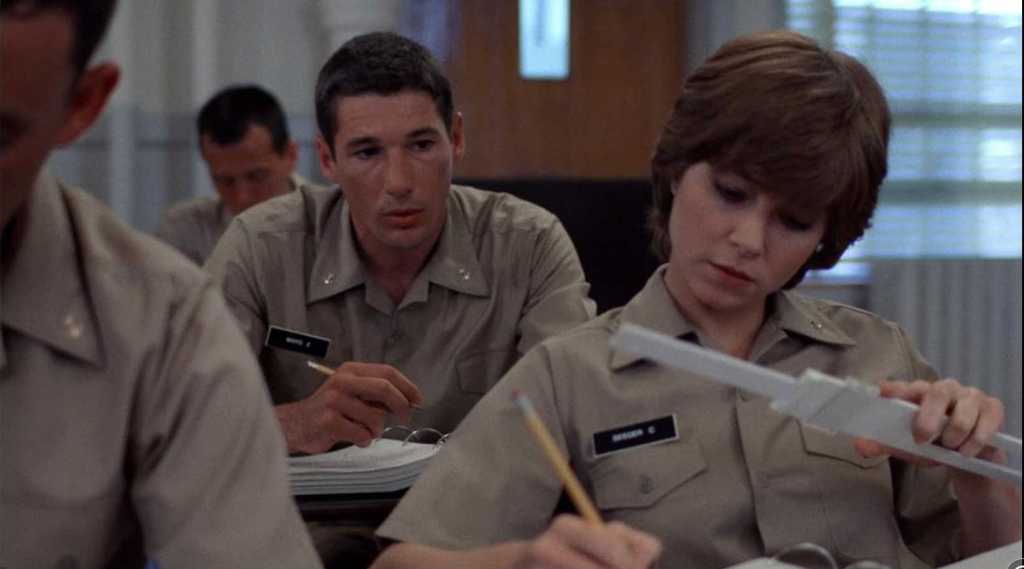

An Officer and a Gentleman was only Taylor Hackford’s second feature as a director, and was written by Douglas Day Stewart, who had previously written screenplays for The Boy in the Plastic Bubble (1976) and The Blue Lagoon (1980) – talk about a problematic movie! – and based An Officer and a Gentleman on his own experience as a Naval Aviation Officer Candidate (AOC). Stewart was ultimately rejected from the program because of a childhood injury, but his screenplay offers an idealized outcome for officer candidate Zach Mayo (Richard Gere), as he struggles to qualify as a naval aviator against the fierce opposition of Marine Gunnery Sergeant Emil Foley (Louis Gossett Jr.) while simultaneously romancing local factory worker Paula Pokrifki (Debra Winger).

The love story set amid military aspirations appealed to audiences. It remains popular today, with a Letterboxd rating of 3.4 as of January 2026. An Officer and a Gentleman was the third highest-grossing film of 1982, after E.T.: The Extraterrestrial and Tootsie. Other top ten films that year included Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan, Porky’s, and Poltergeist. That’s quite a diverse crop of films. Compare that to the top ten grossing movies of 2024, eight of which were sequels or franchise films – did we really need Kung Fu Panda 4? It’s tempting to view every year as a transition point, but it’s hard to argue that the Hollywood of cinephiles was in decline by 1982, despite the variety of filmography available in theaters. Old-school Hollywood legends Lee Strasberg, Henry Fonda, Ingrid Bergman, and Grace Kelly all died that year. Tron used computer animation far more heavily than any previous film, and Star Trek II offered the first entirely CGI visual sequence, a trend that looked a lot more interesting in the 1980s than it does today. The Coca-Cola Company acquired Columbia Pictures, one of a long series of steps that reduced movie studios to corporate assets and, eventually, algorithmic IP streaming platforms. Amid all of this, in the early stages of Western Reagan-Thatcher conservatism, it’s not surprising that a redemptive love story encouraging men to become officers and women to leave the workforce, with a subtle message of conformity and conventionality, would get studio support.

The story is set in and around Port Townsend, Washington, in the Puget Sound area. The location is critical to events. The Port Townsend economy – in the movie and in reality – is heavily blue collar; even today, the Port Townsend Paper Company is one of the area’s biggest private employers. Within the context of the film, the locals have understandable pride in their contribution to the overall economy, manifested in resentment toward the outsiders in slick uniforms who inhabit their bars and date their women, resulting in a bar fight between Mayo and a local. It’s probably not accidental that Paula is of Polish ancestry – large numbers of immigrants from Poland came to the U.S. during 1870 – 1914 and again after World War II. They often sought factory work that many native-born U.S. citizens didn’t want; they were willing to work hard and often brought friends and relatives as co-workers to satisfy the labor demands of a rapidly growing manufacturing sector. Conversely, the Port Townsend locals also resent the monotony and stress of that same factory work and yearn for escape, vividly demonstrated by the “Puget Sound Debs,” personified by Paula and her friend Lynette (Lisa Blount). The women are eager to break free of generational constancy – Paula works at the same factory as her mother (played by the delightful Grace Zabriskie of Twin Peaks fame) – to greener pastures as the wives of aviators.

Despite their common circumstances, Lynette and Paula approach life very differently. Lynette first uses easy sex to seduce AOC Sid Worley (David Keith), then fakes a pregnancy to wrangle a marriage proposal from him. Despite criticism from Paula, Lynette is willing to go to any length to get the life she desires. Only when Worley drops out of the officer program and proposes to her, with the promise of an exciting future in retail in Oklahoma (more on that later), does Lynette acknowledge that it is not the individual she cares about, but the lifestyle. She wants to see the world as a pilot’s wife and doesn’t much care who is sleeping on the other side of the bed. As reward for her deceit, Lynette winds up alone. Given that this happened in the early years of the “Reagan Revolution,” we could put a gender spin on this and believe that Lynette is punished for her ambition and her failure to accept her lot in life. Lynette tries to assume the dominant role in her relationship, repressing the man’s wishes relative to her own.

Paula, on the other hand, has a more fatalistic attitude. She makes no secret about her desire to pursue a relationship with Mayo, and, in fairness, genuinely cares about Mayo. More importantly from a perspective of so-called “family values,” however, Paula allows the man to take the lead in the relationship. This is the movie’s real gender imbalance: Mayo doesn’t save Paula (more on that later), but instead is allowed to be “the decider” based on sheer passivity on Paula’s part. While clearly heartbroken at the prospect that Mayo might leave without her, Paula refuses to follow Lynette’s example. Instead, she accepts her fate and returns to the paper mill. Unlike Worley, Lynette, Mayo’s mother, and even Mayo himself, Paula is not looking for escape at any price. Instead she seeks the sincere stability of marriage and family. Paula is rewarded in the end because she conforms to historic gender roles and lets Mayo decide their future. It helps that, like Mayo, Paula has also lost a parent and now lives with her mother and step-father. (The parents are a microcosm of local attitudes: her mother welcomes Mayo to their home for dinner, while her stepfather remains surly and unimpressed.) Despite expressing unhappiness with the final script and describing the production as “treacherous,” Debra Winger is brilliant in the role and received Academy Award and Golden Globe nominations as Best Actress. An Officer and a Gentleman was only Winger’s third lead role after Urban Cowboy (1980) and Cannery Row (1982) and she already had a reputation for being “difficult.” What some described as “difficult” was seen by others as commitment to her craft. Urban Cowboy director James Bridges shut down production of that film for an entire day while feuding with Winger over a particular scene; yet Bridges later admitted that Winger was correct.

While his influence is never openly acknowledged, Worley deserves some of the credit for the happy ending with Paula and Mayo reunited. Worley not only offers friendship to Mayo, encouraging him to endure the weekend of hell with Foley, but also provides a template of the stability that Mayo lacked throughout his own life. He admires their married peer AOC Perryman (Harold Sylvester), telling Mayo, “Five years of marriage, still in love. That’s what life’s all about.” Later, he confronts Mayo’s selfishness, telling him, “We got a responsibility to the people in our lives. It’s the only thing that separates us from the g-d- animals.” Worley is fully ready to commit to married life with Lynette, even after he learns that she is not really pregnant. Worley’s moral failure – again, viewed from the perspective of a country that was trending heavily toward social conservatism – is his expectation that Lynette will abort her alleged pregnancy. He assumes Lynette will want an abortion and agrees with her, backpedaling on his own stated desires of marriage and family. Is this why the story condemns Worley to take his own life?

Perhaps an equally grave sin in this moralistic landscape is Worley’s decision to abandon the military and return to his former retail career in Oklahoma. This is the point when Lynette ditches Worley and confesses her own shallow aims. Despite modeling the compassion for others that Mayo clearly needs, Worley turns his back on both fatherhood and the aviator brotherhood. Fear of paternal commitment seems uncharacteristic, but Worley’s soft heart will clearly not satisfy the military’s demand for cold-blooded killers. Foley tells his candidates at the start of their training that they must be willing to kill women and children in the line of duty. In my previous viewings of An Officer and a Gentleman, I hadn’t noticed the movie’s violent undercurrent. Foley leads his recruits in running chants that talk about killing “gooks” and napalming women and children. Worley never expresses concerns, but such gruesome acts presented so casually would certainly have troubled him. And in the military build-up led by the uber Cold Warriors of the early 1980s, squeamishness was not acceptable. From day one in office, Reagan ordered expansion of military budgets: a 1981 report from the Center for Naval Analyses called for a 5% increase in number of strategic naval vessels from 1981 to 1982, with corresponding increases in naval aircraft and an expectation of greater increases in following years.

More vessels, of courses, requires more crew members. It didn’t hurt military recruitment that the U.S. economy was in a formal recession during 1981-1982 and domestic manufacturing jobs, which peaked in 1979, declined rapidly in the early 1980s. This made the all-volunteer military a more appealing career prospect for many, and, for some, the only viable and legal option. Increasing military pay during those years added to the incentive, and slicker, more aggressive recruiting campaigns – like the Army’s “Be All That You Can Be” slogan launched in 1980 – gave military service a glamorous luster. His collapse during the pressure chamber test is literal and metaphorical proof that gentle Worley, with his willingness to settle for the life of an assistant retail manager, is clearly out of touch with this culture.

The nation’s financial and cultural military buildup does, however, give Drill Instructor Foley the upper hand in managing his recruits. He tells the AOC group that by the end of the program “I expect to lose at least half of you,” primarily via DOR – Dropped on Request. I might have doubted such an extreme and deliberate attrition rate if I hadn’t lived through Physics 152 during my freshman year at Purdue University. Maybe times have changed, but in my day, some called PHYS 152 the “engineering flunk-out course.” (Thankfully, there was no dunk tank involved.) Classmates who had the scoop from upperclassmen told me that the university’s goal was to drive out 50% of the 400 or so engineering degree candidates in the class. I couldn’t believe the college would be so cutthroat – didn’t they want us all to succeed? – but when I looked around the lecture hall at the end of the semester, roughly half the seats were empty. Like the PHYS 152 instructor – whose name I have long since forgotten – Foley is partly a gatekeeper. He’s not just looking for those with the intellectual and physical aptitude to endure aerodynamics lectures and a lengthy obstacle course, but candidates prepared to sacrifice their ego and individuality to the organized violence of war. There’s a reason words like “subordinate” and “loyalty” are crucial to the character of “an officer and a gentleman,” as defined in the 1922 essay, “The True Meaning of the Phrase ‘An Officer and a Gentleman,’” by Lt. (j.g.) H. E. Dow of the U.S. Naval Reserve Force, a document still displayed on the U.S. Naval Institute’s web site.

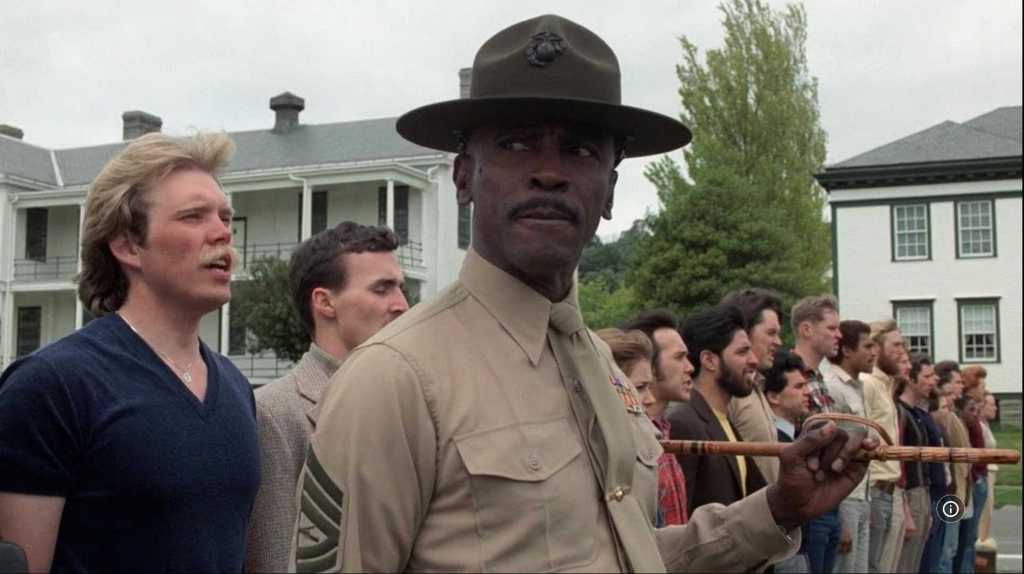

Foley brings with him institutional traditions and customs that foster a sense of shared culture. The candidates not only train together, but raise and lower the flag together; they say a brief prayer together before eating. The candidates are intended to be family as well as colleagues, creating a bubble of social dependency that will inhibit leaving the fold as Worley did. Foley also disparages the anti-establishment culture of the 1960s and early 1970s, accusing the candidates of listening to Mick Jagger and “bad-mouthing your country.” Even Foley’s introduction, polished and disciplined, is a stark contrast to Mayo’s first appearance, long-haired and hungover. In hindsight, it’s impossible to imagine anyone besides Louis Gossett Jr. as Foley. Taylor Hackford specified that Gossett stay in separate quarters from the rest of the cast during filming to encourage a level of detachment between the characters. Gossett already had a lengthy list of stage and screen credits and had military experience as a U.S. Army Ranger. It’s no surprise he received the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor, the first Black actor to receive that award. (Only two Black actors had received any acting Academy Awards prior to Gossett: Hattie McDaniel and Sidney Poitier.)

With experience and discipline on his side, Foley immediately identifies Mayo as the class troublemaker, the candidate Foley most wants to eliminate from the AOC program. He recognizes that Mayo’s overwhelming self-interest make him a poor candidate, such that the younger man needs to be driven out or completely broken down. That Mayo allows himself to be broken down – and that the experience is essential to the film’s upbeat resolution – seems less a testament to Buddhist dissolution of self, and more like a judgment that only conformists deserve a seat at the table. Mayo’s selfishness is evident from the beginning: he rides a motorcycle, a cinematic identifier of rebelliousness since at least the days of The Wild One (1953) and Easy Rider (1969). He rejects assigned bunks and chooses his own bed in a shared room. He operates his own black market business – perhaps a skill he learned in the Philippines? – selling polished boots and belt buckles to candidates unprepared for routine inspections, seeing his classmates as customers instead of peers or friends. He aims to complete the obstacle course in record time in order to distinguish himself from his classmates. His motive to fly jets, never verbalized but plain enough, is to elevate himself literally and professionally above his slacker father.

Mayo’s selfishness is earned through his hard life experiences. The bullying scene early in the film explains why he learned martial arts in self-defense – a skill that comes in handy during the barfight. His father ignored him and his mother escaped in her own fashion, taking her own life, as Worley would do later. He seems to understand that an aimless life with his father is wrong – his dissatisfaction from the first scene is visible – but he lacks the life experience to find a better way. Despite somehow obtaining a college degree in the Philippines, a prerequisite for the AOC program, Mayo has no role models. “You’re all alone in the world,” Mayo tells Paula. “Once you got that down, nothing hurts anymore.” A transparent fib, given Mayo’s ambitions for career and companionship. As he confesses to Foley during the hell weekend when Foley fully breaks him down, the equivalent of the training montage in a Rocky movie, Mayo came to the military because he had no place else to go.

It’s ironic that here in the 21st century, with our lawless and narcissistic ways, Mayo’s selfishness might today be considered a more righteous path. Instead, Mayo gradually learns generosity. He polishes Perryman’s boots and buckles while Perryman is away on leave. In one of the movie’s emotional highlights, Mayo sacrifices his obstacle course ambition to coach Seeger (Lisa Eilbacher) over the wall that has plagued her throughout the program. If An Officer and a Gentleman deserves criticism for diminishing a woman to the extent that she needs saving by a man, this is the scene for it. And yet the moment is so emotionally satisfying that it’s hard to stay angry. The movie glosses over Seeger’s significance, as women still had a minimal presence in the U.S. armed forces in 1982. (Women in the military were still a rarity in 1997, when G.I. Jane, a fictional story of the first woman to complete special forces training, was released.) Despite their noble history in conflict – more than 500 Army nurses served in the Korean War during 1950-1953 – statute and culture kept women out of many prominent military roles for decades. Ultimately, the military embraced women not because it wanted them, but because it needed them after the draft was abolished in 1973. Department of Defense historian Edward C. Keefer wrote, “The way that the all-volunteer force solved its recruiting problems in the late ’70s and the early ’80s was by successfully recruiting women.” It didn’t hurt that the women, on average, were smarter than their male counterparts: “One of the advantages of women in the armed forces was one that they were almost all … high school graduates,” Keefer wrote, “and they scored higher on the mental aptitude tests.” Seeger might be portrayed as physically puny, but her struggle with the wall is necessary to bring out Mayo’s desire to be a team player; yet despite it’s uplifting nature, from a gender perspective it is one of An Officer and a Gentleman‘s weakest moments.

Ultimately all of the characters exist to coax Mayo along the continuum past generosity to full conformity. Yes, he’s still riding his motorcycle in the end, but he does so in full uniform, and he rides it to collect his future bride; no longer a statement of defiance, the motorcycle is reduced to the wheels Mayo can afford until he’s flush enough to buy a more marriage-friendly vehicle. (Chrysler and Renault introduced their first minivans in 1984.) Mayo is so transformed by the end that we might wonder which version of Mayo Paula actually fell in love with. Gere opposed the final scene, Mayo carrying off Paula to the applause of factory workers, but Hackford insisted, and he was right. Despite claims that Paula is dependent on Mayo to save her, the question raised by some critics is, who really saves who in the end? As Gary Susman wrote in Rolling Stone, “When Gere finally sweeps Winger off her feet in the movie’s famous final scene, it’s not because he’s learned to love her, but because he’s learned how to be worthy of her.” The theme of sacrificing an independent streak to get along with others was a theme Gere had also explored in 1980 with American Gigolo, as male sex worker Julian Kay, wallowing in material comfort as a free agent instead of affiliating himself with a madam (or pimp); Kay winds up in prison, accused of murder, until he submits to a wealthy love interest, who subsequently rewards him by leaving her husband and providing an alibi.

Welcome to cutthroat capitalism, where sex work and military service are the only available options for growing segments of the population. Just as American Gigolo only hints at the most disturbing aspects of sex work, An Officer and a Gentleman glosses over the brutal potential of military service. Even the AOC program’s week of “survival training” is only hinted at, never shown. And greater hazards await them in the future. Foley tells his candidates, who are signing on for at least a six-year commitment, that, “Another war could happen in six years.” In fact, during 1982 – 1988, the U.S. military was involved in Lebanon, Grenada, Libya, the Persian Gulf, and Honduras, among other conflicts. This is the life about which Mayo says, “I got nowhere else to go.” The choice between poverty or the life of a male escort in American Gigolo is not really a choice. The alternatives presented in An Officer and a Gentleman, monotonous retail work, even more monotonous factory work, or military service – where “Chemical firms don’t give a sh– that napalm sticks to kids” – aren’t exactly inspiring, either. For its gender politics and embrace of violence, An Officer and a Gentleman is probably a movie we shouldn’t love. Yet the skilled acting, clever emotional wrangling, and hip soundtrack – featuring tunes performed by Joe Cocker, Jennifer Warnes, Dire Straits, and Van Morrison, among others – makes it a hard film to resist. Is it wrong to embrace slick entertainment that can almost double as a military recruitment tactic, just as Top Gun would do four years later? That’s a question with no clear answer as long as the consequences remain unmeasurable. Yet we viewers have what Zach Mayo doesn’t have, a choice, and An Officer and a Gentleman is a choice we should approach with full awareness.

Leave a comment