During 2020 – 2022, I wrote a series of essays about every episode of Star Trek: The Original Series. I’m finally expanding the work to include the original cast motion pictures. This is a link to the TV series essays. If you’re reading this, I assume you have already seen Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan. Also, if you enjoy this essay, please share it on your favorite social media platform so others can discover my work.

“All men live enveloped in whale-lines. All are born with halters round their necks; but it is only when caught in the swift, sudden turn of death, that mortals realize the silent, subtle, ever-present perils of life.”

—Moby-Dick or, The Whale, Herman Melville–

Release Date: 4 June 1982

Director: Nicholas Meyer

Composer: James Horner

Crew Death Count: 2 (Spock and Midshipman Preston are known Enterprise casualties, but we can reasonably assume more, along with most of the crew of the Regula I space station, Captain Terrell, and all of the villains)

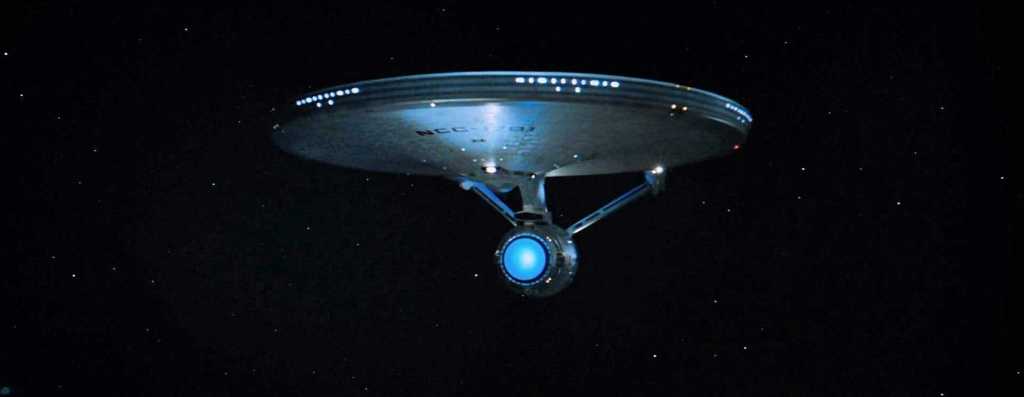

When last we saw the intrepid Enterprise crew, they were about to undertake “a proper shakedown cruise” for their overhauled starship after reuniting to save the earth from V’Ger. Now, three years later, some have learned the lesson of that mission and some, clearly, have not. This time, Kirk and the old crew board the Enterprise, led by Captain Spock, to supervise a training cruise for Starfleet cadets. They are waylaid by their old nemesis Khan (Ricardo Montalban), who has hijacked the USS Reliant (with first officer Chekov on board), which was on a scouting mission to test a radical new Federation project called Genesis. After a long and tense chase, our heroes defeat Khan, but at a terrible price.

Star Trek: The Motion Picture touched on the youth-vs-experience dichotomy – in the end Kirk’s experience as an explorer won the day – but it’s a major theme in Star Trek II (STII). We see this in the opening scene, during an earth-bound training exercise with new-comer Saavik (Kirstie Alley) in command of the bridge. (Omitted from the film was Saavik’s heritage as half Vulcan and half Romulan. This was retained in the novelization by Vonda M. McIntyre.) Wrecking the Enterprise-like simulator, Saavik quickly identifies the nature of the test – it’s a no-win scenario – but doesn’t grasp the intent. Again, Kirk’s experience is the point: “A no-win situation is a possibility every commander may face.” But Kirk, observing his birthday on this very day, feels the burden of age and the urgency of sharing his experience with a next new generation. Kirk is alone, however, isolated from his old shipmates: he is the only one observing the Kobayashi Maru test and not participating. Even Mr. Scott, heard but not seen, is part of the action.

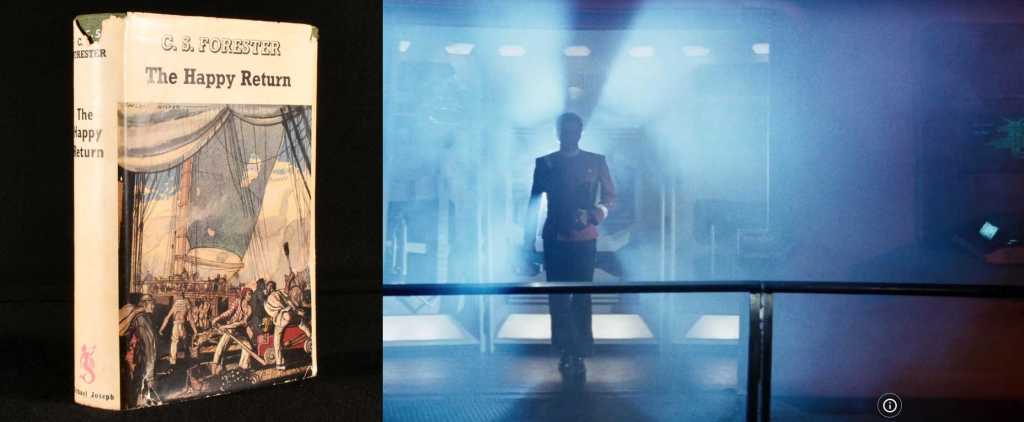

“A man alone” is a recurring motif in STII. Director Nicholas Meyer (who also did an uncredited rewrite of the script) took to heart Gene Roddenberry‘s credit to Horatio Hornblower as an inspiration for the original Star Trek series. Beginning in the 1930s, C. S. Forester wrote a series of novels and short stories about Horatio Hornblower, a fictional British Royal Navy officer during the Napoleonic Wars of the early 1800s. Forester, in turn, took inspiration from the fact that, in the days of slow media, two nations at war could reach a peace settlement, but soldiers and sailors in other parts of the world would remain at war until the news finally reached them. Hornblower was one of those warriors on the periphery, burdened with the responsibilities of command while far from the safety net of home. This is what Kirk was through much of the original series, and what he is about to be again.

We’re given a clearer understanding of Kirk’s solitude during his maudlin birthday “celebration” with McCoy. Spock has already given Kirk an “antique” book, A Tale of Two Cities by Charles Dickens, so McCoy compliments the gesture with his own gift: a pair of antique reading glasses. Depressed by his advancing years, restless at being landlocked, and lacking the immediate threat that V’Ger provided in The Motion Picture, Admiral Kirk seems content to wallow in pity and ignore McCoy’s advice: “Get back your command. Get it back…before you really do grow old.” Kirk has forgotten what he learned in The Motion Picture. He doesn’t need command as an end in itself, but for what it gets him: “Galloping around the cosmos,” exploring the galactic frontier with his friends, because these friendships are the defining experience of his life. While a starship captain might be alone in bearing the responsibilities of leadership, Kirk has never been more alone than he seems in his own home, which comes with a fabulous view and the antique collection of someone who embraces the lessons of history as much as he is preoccupied by nostalgia.

Kirk’s emotional state seems to improve when he boards the Enterprise for an inspection and a training cruise. The mission may be fake but his friends are here and he even gets to mediate a heated debate between Spock and McCoy. Even better, Kirk again takes command of the Enterprise from her intended captain when a distress call arrives from Kirk’s lost love, Carol Marcus (Bibi Besch); in contrast to the emotional confrontation with Decker in The Motion Picture, this time the transition of power is smooth. The “needs of the many” conversation between Kirk and Spock is one of the most poignant and best-written scenes in the entire Trek franchise. For a brief moment, Kirk is back where he wants to be.

The serotonin boost doesn’t last, however: soon enough Kirk’s experience is being tested in new ways. Failing to heed the voice of youth – Saavik’s reminder about regulations – Kirk nearly gets the Enterprise and her crew wiped out in a surprise attack by the Reliant. All of the old patterns are inverted. The music clues us in to this: instead of Jerry Goldsmith‘s brilliant, sweeping orchestral score from The Motion Picture, James Horner‘s equally brilliant score is leaner and punctuated by tension and conflict. This time around, instead of flirting with a scantily-clad yeoman, Kirk faces the reality of absentee fatherhood (more on David Marcus later), not an absence that Kirk chose but a forced absence because this time the woman rejected him. “You had your world and I had mine,” Carol Marcus says, “and I wanted him in mine.” How many times has that happened? Kirk not only ignores the current voice of youth, but his own youthful adventures. This is the guy who, as a cadet, reprogrammed the Kobayashi Maru simulator: “I changed the conditions of the test.” Now, however, Admiral Kirk is at a loss for answers while his nemesis keeps changing the usual conditions. (Kirk and Spock using Reliant‘s prefix code against her is a fluke, and doesn’t make up for Kirk’s previous carelessness.) And that’s not the only way the past comes back to haunt the admiral. This time the enemy is someone who nearly defeated Kirk fifteen years ago, someone who has bitterness to match Kirk’s solitude. Because Kirk isn’t the only man alone in this tale.

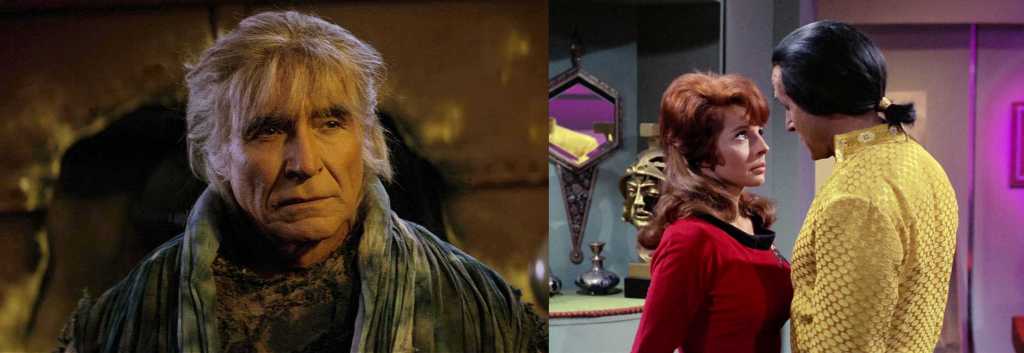

Like Kirk, Khan is haunted by a lost love. In sheer age, Khan is nearly as old as the antiques in Kirk’s collection. Having been set adrift in space as punishment for trying to take over the earth in the 20th century, Khan and his followers were revived by the Enterprise crew in the first season TOS episode “Space Seed.” That episode concluded with Kirk offering Khan, who very nearly succeeded in hijacking the Enterprise, a choice: prison or a life of freedom on the harsh and unsettled Ceti Alpha V. Being a student of John Milton, Khan chooses the riskier path, believing it is “better to reign in Hell than serve in Heaven.” At that time, Khan took Enterprise crew member Marla McGivers (Madlyn Rhue) as his mate. We learn early in STII that McGivers died soon after the events of “Space Seed.” For fifteen years Khan has stewed in his anger, setting up another literary reference, Herman Melville‘s Moby-Dick. Khan paraphrases Moby-Dick twice:

| Khan: | Moby-Dick: |

| “He tasks me — and I’ll have him. I’ll chase him round the moons of Nibia and round the Antares maelstrom and round perdition’s flames before I give him up.” | “Aye, aye! and I’ll chase him round Good Hope, and round the Horn, and round the Norway Maelstrom, and round perdition’s flames before I give him up.” “He tasks me; he heaps me…” –Chapter 36– |

| “To the last, I will grapple with thee… From hell’s heart I stab at thee… For hate’s sake… I spit my last breath at thee!” | “Towards thee I roll, thou all-destroying but unconquering whale; to the last I grapple with thee; from hell’s heart I stab at thee; for hate’s sake I spit my last breath at thee.” –Chapter 135– |

We shouldn’t be surprised that Khan is versed in Moby-Dick, because we see a copy of it on his shelf, along with Milton’s Paradise Lost, Dante’s Inferno, and Shakespeare‘s King Lear. “How can I live without thee,” Adam mourns in Paradise Lost, when he learns that Eve has doomed them by consuming the fruit of the tree of knowledge, “how forgoe, Thy sweet Converse and Love so dearly joyn’d, To live again in these wilde Woods forlorn?” Did literature comfort Khan after McGivers’ death, or did it fuel his blame of Kirk? Regardless, McGivers is the lost limb that sets Khan off on a quest for vengeance that, like Ahab’s, will become all-consuming. It’s no coincidence that Khan’s bookshelf has only Inferno, the first cantica of Dante’s Divine Comedy. Inferno offers a tour of sin in the Underworld; the remaining cantiche, Purgatorio and Paradiso, ascend through Purgatory and into Heaven. In his grief, Khan could never have seen past the Inferno. This is why Khan ignores Joachim’s urging, “You have Genesis! You can have whatever you [want]!” This is Khan’s rejection of the beneficial potential of Genesis to render a new world, the very paradise that he and his followers first sought to build on Ceti Alpha V. (Khan apparently neglected to read Milton’s Paradise Regained, in which Christ is triumphant over Satan. Spock is clearly the Christ figure in this story.)

Like those sailors of long ago, unaware that the war had ended, Khan has been isolated for fifteen years. But he really lives in an even more distant past, having barely seen enough of the 23rd century during “Space Seed” to be fully caught up. As Spock says, while Reliant and Enterprise play cat-and-mouse in the Mutara Nebula, Khan is “intelligent but not experienced.” And just as Kirk regrets ignoring Saavik’s advice, Khan ignores the sage advice of his number two, Joachim (Judson Scott), to let Kirk go and get about the business of conquering the galaxy. One of the few things that has always troubled me about STII is how young Khan’s followers look. They seem too young to have been present during the “Space Seed” era, but too old to be offspring of Khan’s original group. Judson Scott was born in 1952 and would have only been 14 years old when “Space Seed” aired, and he was nearly 30 years old when STII was released. Steve Bond, identified as “Khan’s Crewman #1,” was born in 1953. Laura Banks, “Khan’s Navigator,” was born in 1956. The math doesn’t quite work and I find it distracting that Khan’s followers are the wrong age.

Youthful enthusiasm is also a trait of Midshipman Peter Preston (Ike Eisenmann), who doesn’t shy away from expressing his pride in Mr. Scott and the Enterprise during Kirk’s engine room inspection. The exchange comes back to us when Preston dies during the Reliant attack, having “stayed at his post when the trainees ran,” according to Scott. In a scene that was deleted from the theatrical release, but restored to later versions, Scott identified Preston as his nephew. It explains Scott’s trauma over Preston’s death and gives some much-needed depth to one of our long-time supporting characters. Preston’s death is another signal that this is not the usual adventure – perhaps not since the death of Kirk’s brother in “Operation – Annihilate!” has the crew suffered such a personal loss. In terms of the rest of our long-time supporting cast, Chekov also gets more visibility thanks to being Reliant‘s first officer. Uhura and Sulu have a little more activity than they had in The Motion Picture, but otherwise still don’t get a lot to do.

As if Saavik, Joachim, and Preston weren’t enough youth power, Kirk is reunited with his long-lost son David (Merritt Butrick) when the Enterprise responds to the distress call from the Regula I science station. David resents Kirk even before he learns of the family connection, viewing the admiral as a representative of military intervention: “Scientists have always been pawns of the military.” What experience has brought him to this attitude? In this regard, David is trapped in his own solitude, inflexible compared to his mother, who sees more nuance in human behavior. It’s intriguing that David and, presumably, his peers on Regula I, view Starfleet as “the military” and not the intrepid explorers they’ve been presented as. Only after seeing Kirk and the Enterprise crew in action, while on the bridge during the climactic battle and escape, and seeing their response to Spock’s death, does David understand that the world is more complex than he had known.

David Marcus isn’t entirely alone in self-righteousness as long as Dr. McCoy is along for the ride. Unlike Kirk, McCoy remembers very well the lesson of The Motion Picture: his “first, best destiny” is not just as a physician, but to counsel his friends and keep their worst impulses in check. It’s the doctor who first urges Kirk to get out from behind a desk. And with the possible exception of David Marcus, only McCoy seems to grasp the true significance of Genesis, that it will inevitably be used as a weapon. McCoy’s claim, “We’re talking about universal armageddon,” might be a bit of an exaggeration, but he is wise to recall the violent tendencies that still haunt the nature of humans and other species. McCoy also gives Kirk the pep talk he needs to hear and unwittingly provides a host for Spock’s katra during the movie’s climax; not such an odd choice after the events of the season two episode “The Immunity Syndrome.” In the end, McCoy asks Kirk the question that will propel our characters through the next two films: How do you feel?

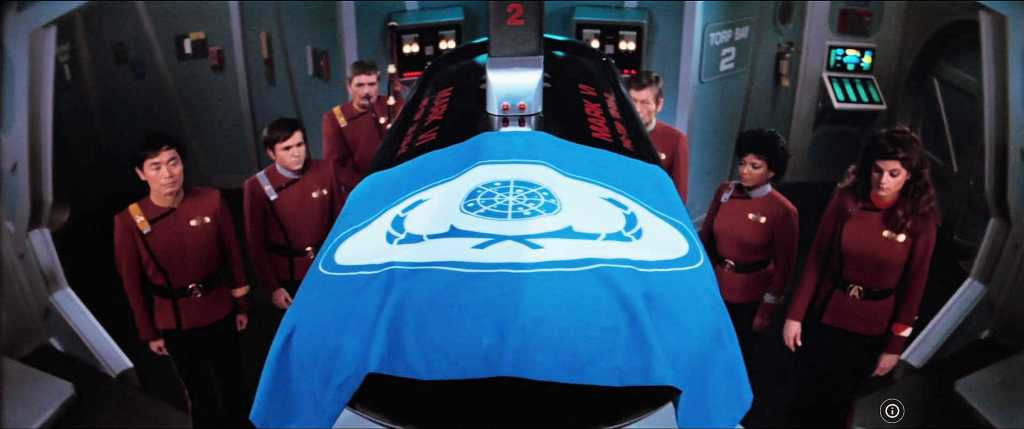

That’s the question triggered by mourning over Spock’s ultimate sacrifice, giving his life to save the crew. Spock’s birthday gift to Kirk, A Tale of Two Cities, was well-chosen, the Kirk recalls the book’s closing lines at movie’s end: “It is a far, far better thing that I do, than I have ever done; it is a far, far better rest that I go to, than I have ever known.” In Dickens’ novel, those are the final thoughts of Sydney Carton, who felt such love for the novel’s heroine, Lucie Manette, that he gave his life to spare Lucie’s husband Charles Darnay. Similarly, Spock, in his own way, loves the Enterprise – he is her captain, after all – and her crew, and calmly accepts his own sacrifice to save them all. Of all the “man alone” stand-ins in ST II, Spock’s situation is the most extreme. This is reflected in the movie’s final subversion of the original series tropes, by delivering the mission statement, “Space, the final frontier,” at the end of the voyage rather than the beginning, and spoken by Spock this time rather than Kirk.

During the memorial ceremony for Spock, Kirk says, “Of all the souls I have encountered in my travels, his was the most human.” He doesn’t mean that literally, of course. He means that Spock achieved a degree of integrity that most humans only aspire to, that he was, in some ways, the best of all of them. Yes, Spock reacquired a dose of humanity in The Motion Picture, but that emotional quality needs the thoughtfulness of a Vulcan to gain true meaning. There’s a reason Spock precedes “the needs of the many outweigh the needs of the few” with the phrase, “Logic dictates…” Such wisdom and generosity were only possible with the combination of Spock’s mixed ancestry and his life experience.

We know that Carol and David Marcus developed Genesis. Kirk appears to have had a supervisory role, but his exact contribution to the project remains vague. Does he feel any guilt? It’s an important question because Khan’s possession of Genesis caused Spock’s death, and because, as we will see in Star Trek III: The Search for Spock, a kind of arms race has now been unleashed on the galaxy. Is Genesis a metaphor for nuclear weapons? The Cold War was fairly hot in 1982: the Soviet Union had invaded Afghanistan in 1979, the U.S. had boycotted the 1980 Summer Olympics in Moscow, and Ronald Reagan took an aggressive stance toward the USSR when he entered the White House in January, 1981. I remember serious discussions about the possibility of nuclear war among me and my classmates during the early 1980s. Nicholas Meyer would soon invest himself heavily in research of weapons of mass destruction as director of the 1983 made-for-TV movie The Day After, about the survivors of a nuclear exchange between the U.S. and Soviet Union. The profound difference, of course, is that Genesis at least leaves new life in its wake, and for that reason I think Genesis primarily symbolizes what the entire movie has been telling us: sooner or later, the original crew will have to hand over the reins to the next generation. Time consumes us all.

Time is one thing that distinguishes STII over the The Motion Picture; this time we have a patient resolution, giving the characters room to absorb the circumstances of their strange new world. Nicholas Meyer’s preferred title for STII was the title he would end up using for Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country. It’s a line from another tale of grief and loss, Hamlet: “But that the dread of something after death, The undiscovered country, from whose bourn, No traveller returns…” In the Genesis cave on Regula I, Kirk says, “I don’t believe in the worst-case scenario;” as he did in the Kobayashi Maru simulator, Kirk is still dispensing witty sayings for the benefit of trainees. When the admiral inevitably faces a no-win scenario first-hand, he finally understands the role that luck has played in his past adventures and now luck has caught up with him. When you add up the risks over the years, the true miracle is how so many of the crew have survived so long. Death is the undiscovered country, the end that we all face but never entirely understand or even expect. “But the stars that marked our starting fall away,” Dante wrote in Inferno, “We must go deeper into greater pain, for it is not permitted that we stay.” In response to McCoy’s question, Kirk answers, “I feel young,” and the rest of the crew seems to agree. They are flush with victory and basking in the light of the new Genesis planet. But the cold of space and the uncertain future still await. The crew might seem resolved with their loss at the end, but we know this is fleeting. Greater pain awaits.

Next: The Search for Spock (1984)