During 2020 – 2022, I wrote a series of essays about every episode of Star Trek: The Original Series. I’m finally expanding the work to include the original cast motion pictures. This is a link to the TV series essays. If you’re reading this, I assume you have already seen Star Trek III: The Search for Spock. Also, if you enjoy this essay, please share it on your favorite social media platform so others can discover my work.

“In fact, four men such as they were—four men devoted to one another, from their purses to their lives; four men always supporting one another, never yielding, executing singly or together the resolutions formed in common; four arms threatening the four cardinal points, or turning toward a single point—must inevitably, either subterraneously, in open day, by mining, in the trench, by cunning, or by force, open themselves a way toward the object they wished to attain, however well it might be defended, or however distant it may seem.”

–Alexandre Dumas, The Three Musketeers—

Release Date: 1 June 1984

Director: Leonard Nimoy

Composer: James Horner

Crew Death Count: 0 (This is deceptive considering all the other deaths that occur, including the crew of USS Grissom and, of course, David Marcus.)

How do we carry on after the death of a loved one? It’s a sorrow we’ll all experience sometime in life, and it’s the question we’re asking at the beginning of Star Trek III: The Search for Spock (STIII). After defeating Khan, yet losing Spock while escaping the Genesis device, Kirk’s son David Marcus (Merritt Butrick) and Saavik (Robin Curtis), along with the crew of the USS Grissom, stay behind to explore the newly formed Genesis planet. Meanwhile, the Enterprise crew returns to earth to a double-whammy of bad news: the Enterprise is to be scrapped and McCoy appears to be having a nervous breakdown. Sarek (Mark Lenard) soon arrives to confirm that McCoy actually carries Spock’s katra, or “soul,” which needs to be reunited with Spock’s body. Kirk and company hijack the Enterprise, compete with Klingons for control of the Genesis planet, and ultimately need to destroy the Enterprise to save themselves. The real tragedy is that the Klingons, led by Kruge (Christopher Lloyd), kill David Marcus. The good news is that Spock miraculously regenerates with the Genesis planet. The fal tor pan ceremony unites Spock’s katra with his body and Spock’s memory begins to return.

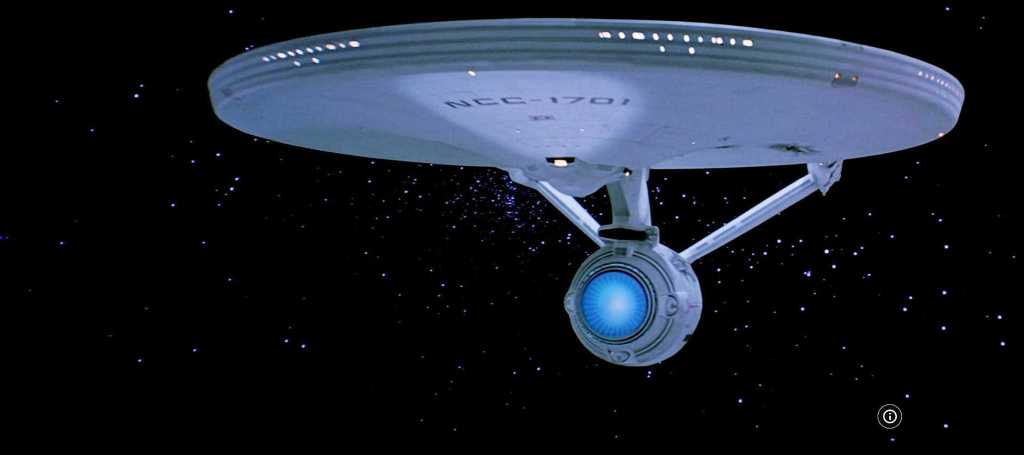

After a brief flashback summarizing the tragic end of Star Trek II, we open with the Enterprise en route to Earth. “I feel uneasy,” Kirk says. And, later, “This time we’ve paid for the party with our dearest blood.” This is visualized by the Enterprise itself, which remains scarred from the battles with Khan, symbolizing the emotional scars of our characters. The feeling of age and weariness, already explored in STII, is reinforced when the crew is greeted by Admiral Morrow (Robert Hooks), the vaguely-titled Commander, Starfleet, who tells them the Enterprise will be decommissioned. As odd as that might seem for a ship that was fully renovated only a few years ago, the message is clear: time, and decades of risk, are catching up with them all. Do they have any more adventures left in them?

Thankfully, Sarek’s visit reignites some of the old fire. We haven’t seen Sarek, Spock’s father, since “Journey to Babel,” when Spock and Sarek seemed to patch up their long-time dispute over Spock’s career choice. Given how much time they’ve had to nurture that relationship, it’s no wonder Sarek seems agitated over Spock’s death. It also seems significant that Sarek is still the Vulcan ambassador to the Federation, and is familiar with the Genesis program, which seems as classified as a DoD Signal chat. He clearly has considerable seniority within the Federation. Sarek’s poignant mind-meld with Kirk not only recalls an absent colleague but reminds us how unsettled everyone is over Spock’s absence. One inconsistency that has always distracted me is Sarek’s description of reuniting Spock’s katra (the “living spirit,” everything that is not of the body) with his corporeal self; Sarek presents this as a commonplace event. “It is the Vulcan way when the body’s end is near,” he tells Kirk. Yet, in the end, Vulcan priestess T’Lar (Dame Judith Anderson) indicates that fal tor pan is rare and dangerous.

The grief over Spock’s death, alongside McCoy’s mysterious affliction, is compounded by the characters’ general awkwardness: we’re not used to seeing them on earth and dealing with Federation bureaucracy. They are like immigrants to their own home world. It’s unlikely McCoy would have had luck chartering an illicit ship even in his right mind. Life sure was easier out on the periphery of explored space where a little entrepreneurial attitude went a long way. This helps explain why the Enterprise crew chose careers of exploration in the first place. Day-to-day administrative headaches seem like a colossal waste of time after battling Romulans. (Look at some of the Apollo astronauts: divorce, autograph feuds, and space alien conspiracies were some of their antics after the spectacle of walking on the moon.) “Starfleet is up to its brass in galactic conference,” Kirk says in frustration. Yet Starfleet’s position – that the Enterprise is due for replacement and “Vulcan mysticism” sounds darn sketchy – is hard to argue with, especially with the ultra-hip USS Excelsior standing by to give transwarp drive a trial run. (What is transwarp drive? It won’t be mentioned again in the original cast movies.) Residents of earth, whether involved with the Federation or not, must see these galactic explorers as eccentrics constantly making irrational demands. (Won’t it later be Picard’s arrogance toward Q that invites premature introduction to the Borg? Who can blame earth’s residents if they’re sick of this whole “strange new worlds” business?)

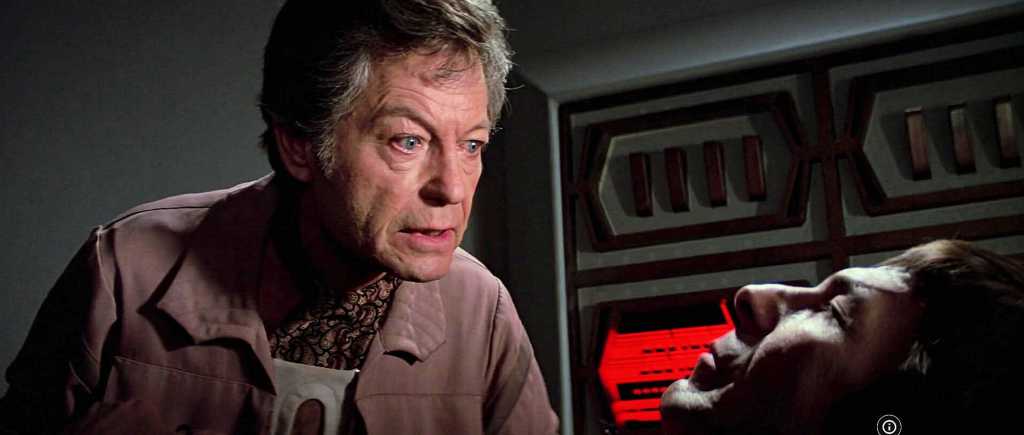

McCoy gets the worst of this as the one who is Baker-acted over a little unconventional behavior. (Okay, he violated a security directive, broke into Spock’s quarters, and tried to charter a ship to a restricted area, fair enough.) The doctor’s situation is played for mild humor, but look at the prison cell he’s kept in. What kind of progress is this? Much as the ill or elderly in our own time are dependent on friends and family to save them from a corrupt healthcare system, McCoy only makes it through this because of the jail-break staged by his comrades. And the irony is clear, that this has all been inflicted on the doctor by his long-time verbal sparring partner. Later, McCoy has the moment he needs with Spock, but only when Spock is unconscious. “I don’t know if I could stand to lose you again,” McCoy says. This reflects a similar scene from “The Immunity Syndrome;” McCoy wished Spock luck in his mission to confront the giant space-amoeba, but only when Spock was too distant to hear. Of course, the banter between these two explorers has always been mostly a bluff. They don’t argue because they dislike each other, but because McCoy is too intense and Spock is too reserved to express the true depth of their friendship. Finally, why does McCoy introduce himself to T’Lar as “son of David”? Is the doctor simply respecting the formality of the situation? Or is this a Biblical reference? In the New Testament, it was important that Jesus be in the lineage of King David, because of the claim in the Old Testament’s 2 Samuel that the future Messiah would be a son of David. Biblically, Jesus fulfilled a prophecy of eternal life, and by this point in the film there is no doubt that McCoy possesses whatever intangible substance will allow Spock to live again.

The need for fal tor pan brought the renegade Enterprise crew to the Genesis planet, but not in time to save the crew of USS Grissom, killed by the Klingons while surveying the new world. Two ticking clock scenarios collide at this point, Kruge’s obsession to obtain the Genesis “weapon” (more on the Klingons later), and the rapid self-destruction of the Genesis planet as a result of David Marcus’ moral failure. Marcus reveals to Saavik that he used “protomatter,” which Saavik describes as “an unstable substance which every ethical scientist in the galaxy has denounced as dangerously unpredictable.” (Protomatter will be referenced again in Deep Space Nine and Voyager.) Did Carol Marcus know about David’s use of protomatter? Does this help explain her absence from this mission? Either way, it’s a subtle commentary on the importance of ethical conduct in scientific research, something that is sometimes corrupted in our own time by politics and the introduction of profit incentives. “Move fast and break things” was never a good idea.

Should we interpret David’s death as karmic retribution for his past choices? We do know he has come a long way from the moody young scientist we met early in Star Trek II. The look David exchanges with Saavik when he learns that Kirk has arrived is a telling and brilliant moment. The young scientist who hated his absent father has come to regard Kirk as the cavalry come to save the day. And in most stories, that would be true. Yet the search for a test planet for Genesis in Star Trek II is what gave Khan a starship and set all of these events in motion. However we interpret these events, David redeems himself in the end by intervening when the Klingons attempt to execute Saavik. And Saavik’s salvation could equally be seen as a karmic reward for providing the story’s moral center. Not only does she call out David on his use of protomatter, but she guides a young and confused Spock through pon farr. (The movie tactfully dodges the long-term implications of the pon farr experience.)

In attacking the Grissom, pursuing Genesis, and killing David, Kruge and his crew appear to be a rogue element within the Klingon Empire. “Even as our emissaries negotiate for peace with the Federation,” Kruge says, “we will act for the preservation of our race!” Are serious peace negotiations in progress between the Federation and the Empire? Is this perhaps a direct result of the Genesis detonation in Star Trek II? Remember Kirk’s comment about Starfleet being “up to its brass in galactic conference.” Is he referring to a real live conference? This puts a whole new spin on the film’s events and foreshadows Star Trek VI. As always, the question of motives arises: is Kruge really acting on behalf of Klingons everywhere, or pursing his own power trip? He comes across as Khan minus the revenge motive, intelligent but more deliberate in his actions. Kruge is a clever tactician, deducing that he faces a weakened Enterprise. I confess, I was skeptical of Christopher Lloyd as a suitable Star Trek villain, having only been familiar with his kooky character on the series Taxi (1978 – 1983). Yet Lloyd’s performance holds up very well, from his ruthlessness in killing his messenger Valkris (Catherine Shirriff) to the urgent plea to his crew when he learns that Kirk has tricked them into boarding a self-destructing Enterprise.

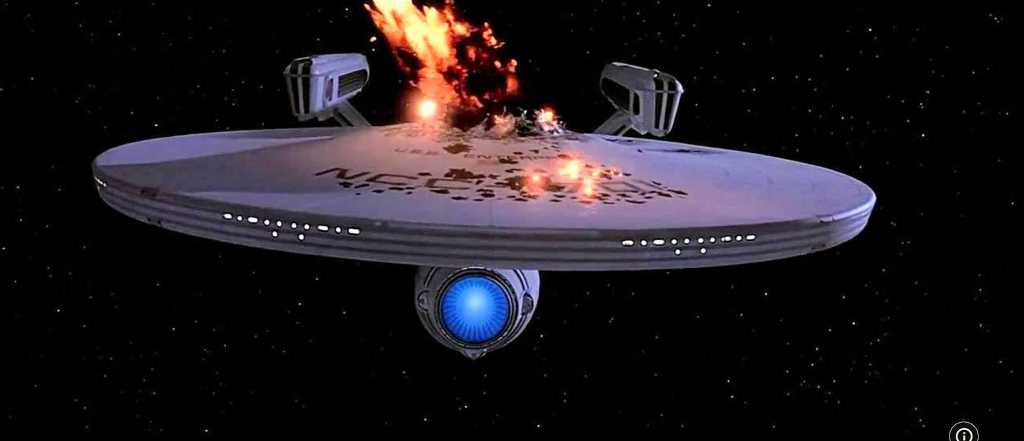

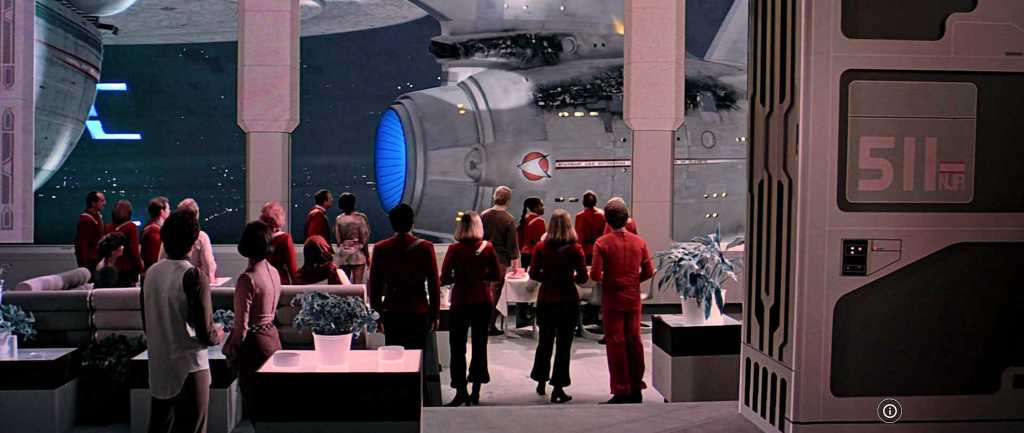

Kirk’s ploy, allowing Kruge’s crew to board the Enterprise only to blow up the ship, is a heart-breaking confirmation of what we could only speculate from a dramatic scene in the Season 3 episode “Let That Be Your Last Battlefield.” In that episode, we could only wonder if the elaborate self-destruct protocol was one of Kirk’s famous bluffs. Now we learn the truth in one of the most powerful images from the entire franchise. (Since then, destroying the Enterprise has become an over-used stunt, diminishing the impact of the moment.) This scene also builds on Kirk’s statement to David in Star Trek II: “I’ve cheated death. I’ve tricked my way out of death and patted myself on the back for my ingenuity.” He may have tricked death again, but there will be no such self-congratulation this time. As the crew watches their beloved ship burn across the sky, they have never looked more hopeless. (And this act will come back to haunt them, particularly Kirk, in the future.)

By this point, Kirk has already suffered the even greater loss of his son’s death. Hopes were raised early in the film for a smooth mission, what with the successful rescue of McCoy and the ease with which they hijack the Enterprise. (This means that, in one way or another, Kirk has seized command of the Enterprise in all three movies.) Yet it’s just after McCoy’s liberation when Kirk says, “The Kobayashi Maru has set sail for the promised land.” The Kobayashi Maru, established in Star Trek II, is a no-win scenario. How could we expect anything else? In a story entirely about tricking death – reviving Spock by restoring his katra – we should expect nothing less than a cosmic rebalancing.

This is Sarek’s observation as we near the end: “But at what cost? Your ship. Your son.” Friendship has been a common theme throughout Star Trek, but this time it is the entire point of the story. Leonard Nimoy described Star Trek III by asking, “What should a person do to help a friend? How deeply should a friendship commitment go?” In “Amok Time,” we witnessed how much Kirk would sacrifice for his friendship with Spock. Now time has amplified both the friendship and the sacrifice. “I have left the noblest part of myself back there on that newborn planet,” Kirk says at the start of the film. Again, we’re building on Star Trek II, when Kirk referred to Spock as the “most human” of all the souls he has known. Not human in a literal sense, but as someone who has achieved a human ideal of nobility and sacrifice. By risking their careers, and their lives, and returning to the Genesis planet, the crew is repaying the sacrifice that Spock made for them in Star Trek II.

Friendship here is about much more than the Kirk-Spock relationship or the McCoy-Spock relationship. We see it in Saavik’s compassion for young Spock’s struggles as he matures at an unnatural rate. And while Saavik disapproves of David’s use of protomatter, she doesn’t disown him for it. We see the loyalty of Uhura, Sulu, Chekov, and Scott, who have been too neglected over the years and finally get a piece of the action in STIII. Fully understanding the risks, they’re all eager to sign on for this mission. Not only that, they all perform acts far removed from their usual duties: these are the passionate, well-rounded characters we’ve been waiting for. And all in the name of friendship. Spock doesn’t fully have his mind back, and the losses have been considerable, but the team is together again and closer than ever.

We could easily interpret all of this as a cynical clinging to nostalgia, dragging a tired, middle-aged crew around the galaxy to make a buck. (Only two years later, planning The Next Generation, Paramount executives called the Star Trek franchise “our priceless asset.”) But most of the main cast members were only in their late forties or early fifties at the time. Still, they’ve been “hopping galaxies” for nearly twenty years, and we could do a lot worse than learn from their examples. When Kirk tells Spock, “The needs of the one outweigh the needs of the many,” he doesn’t mean that literally. It’s a rephrasing of the motto of The Three Musketeers: one for all, all for one. A similar sentiment came earlier from Aesop’s Fables: united we stand, divided we fall. Kirk really means that they’re all in this together, friends till the end, and their years of shared service have only strengthened that bond. Experience matters, and whether they’re defeating Klingons or demonstrating friendship for the ages, these role models remain timeless in any century.

Next: The Voyage Home (1986)