During 2020 – 2022, I wrote a series of essays about every episode of Star Trek: The Original Series. I’m finally expanding the work to include the original cast motion pictures. This is a link to the TV series essays. If you’re reading this, I assume you have already seen Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home. Also, if you enjoy this essay, please share it on your favorite social media platform so others can discover my work.

Release Date: 26 November 1986

Director: Leonard Nimoy

Composer: Leonard Rosenman

Crew Death Count: 0 (Woo hoo! Granted, we have a very small crew this time, but still…)

“What if the catalyst or the key to understanding creation lay somewhere in the immense mind of the whale? … Suppose God came back from wherever it is he’s been and asked us smilingly if we’d figured it out yet. Suppose he wanted to know if it had finally occurred to us to ask the whale. And then he sort of looked around and he said, ‘By the way, where are the whales?’”

–Cormac McCarthy, Whales and Men—

The Enterprise crew has accomplished a lot in only three movies, and they have also suffered great losses. Decker and Ilia disappeared, Spock died, David Marcus died, the Enterprise was destroyed; so despite Spock’s rebirth in Star Trek III, a focused adventure to save the earth might be just the ticket to distract us from so much grief and deep thoughts. And that’s just what we get with Star Trek IV (STIV). Bound for earth in their captured Klingon Bird of Prey, with Spock still not fully himself, the crew learns that a mysterious probe has approached earth. The probe is causing such havoc that no one on earth is expected to survive. Deducing that the probe is emitting the sounds of humpback whales, which are extinct in the 23rd century, the crew travels back in time to 1980s San Francisco, collects two humpback whales, along with cetologist Dr. Gillian Taylor (Catherine Hicks), and splashes down in San Francisco Bay just in time to save the world and be generally forgiven for their misdeeds in Star Trek III.

The opening of STIV is reminiscent of 1979’s The Motion Picture. A mysterious entity with planet-destroying power approaches earth, after first being observed on the Federation’s periphery. In this case, the probe is initially encountered by the USS Saratoga, led by an unnamed captain played by Madge Sinclair. Sinclair had the distinction of playing the first female captain in the Star Trek franchise. (Sinclair also played Geordi La Forge’s mother in an episode of The Next Generation.) Admiral Cartwright (Brock Peters) reports that multiple starships have been “neutralized,” without specifying what that means, so we’re not entirely certain of the Saratoga‘s outcome. One significant difference between V’Ger and the probe is that V’Ger had a reasonably defined purpose that required human intervention to fulfill. The probe also requires human intervention, but only to atone for past human failures. (More on that later.) We can assume that the probe was looking for some communication from the whales, but to what end? I actually appreciate the filmmakers’ decision to leave this as something of a mystery.

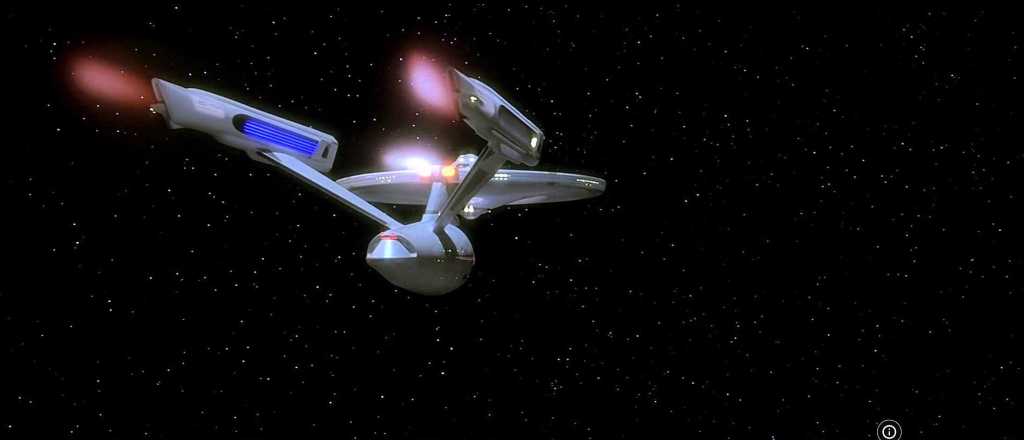

The political climate that our characters face is efficiently established: they are expected to stand trial for defying orders and hijacking the Enterprise in Star Trek III, and well they should. Sarek (Mark Lenard) returns and his sparring with the Klingon ambassador (John Schuck) demonstrates why Sarek is still the Vulcan ambassador to the Federation. This exchange also reminds us of the challenges of interpreting events that took place in remote space: what the Federation regards as internal house-cleaning is viewed as war planning by the Klingons. Some personal dynamics are also laid out in these early scenes: Saavik (Robin Curtis) is withdrawing from the journey. It’s sad to bid her farewell, but there clearly wasn’t much of a role for the character in this film. (The script originally had a more explicit explanation, that Saavik was pregnant with Spock’s child after undergoing pon farr in Star Trek III. Thankfully, we’re spared the awkwardness of Spock skipping out on his pregnant lover.) The rest of the crew is resolved to return to earth, and it’s interesting that Kirk still records captain’s log entries despite being on a Klingon vessel. (Don’t look at the bridge too closely, because it is redesigned from Star Trek III.) The crew nicknames their ship Bounty, recalling the mutineers of the HMS Bounty in the South Pacific in 1789. Let’s be grateful the name is only tongue-in-cheek, because the real-life Bounty mutineers, led by Fletcher Christian, engaged in life-and-death conflict among themselves and with indigenous peoples.

Of course, Spock’s absent-mindedness is the most notable character status, as he recovers from the tumultuous events of Star Trek III. The lighter tone of this film means that Spock’s emotional state will be easily resolved, but what a joy that the journey is launched by Spock’s mother Amanda (Jane Wyatt), who we haven’t seen since Season 2’s “Journey to Babel“. “How do you feel?” is Amanda’s question – the same question McCoy asked Kirk at the end of Star Trek II – reminding us that her human DNA is part of Spock’s nature, whether he acknowledges the fact or not. This somewhat revisits Spock’s character growth from The Motion Picture, but the poor guy was dead, so a little repetition seems reasonable. “I do not understand the question,” is Spock’s initial response to Amanda. In yet another parallel to The Motion Picture, the experience of saving the earth is what gets Spock to, if not a thorough understanding of the question’s relevance, at least the ability to provide an answer: “I feel fine.”

Unlike The Motion Picture, most of this mission takes place directly on earth, primarily in or near San Francisco. Increased location filming offered a reduced need for expensive visual effects but created other challenges. (The biggest challenge from Paramount’s perspective seems to have been Shatner’s and Nimoy’s salaries, which provided a catalyst for developing The Next Generation.) Still, it’s fun to see our heroes navigating contemporary earth, and in a more sophisticated way than the series’ time travel episodes allowed. The time travel sequence itself, the slingshot-around-the-sun maneuver recalled from “The Naked Time” and “Tomorrow is Yesterday,” is handled more artistically this time, foreshadowing bits of future dialogue and the dreamlike prospect of a three-hundred-year shift in mindset.

Once on earth, of course, sourcing a pair of humpback whales, with the help of Dr. Taylor, becomes paramount. (No pun intended.) Taylor is the perfect bridge between the Enterprise crew and 1980s humanity: she can interpret “terra incognito” for the future travelers, but she is forward-thinking enough to adapt to the twenty-third century after she hitches a ride on the Bird of Prey. Despite a little flirting between Taylor and Kirk, it’s a blessing that the filmmakers didn’t go for another quickie Kirk romance. This allows more dignity and credibility for both characters, and we’re left with the feeling that Taylor will adapt quickly to her new life in the 23rd century.

This dynamic also keeps Kirk focused on the mission. One of the film’s most touching moments occurs just after the whales have been rescued and Kirk, who we know as a lover of literature, shares a passage from the D.H. Lawrence poem Whales Weep Not!, published posthumously in 1932: “They say the sea is cold, but the sea contains the hottest blood of all.” (Be forewarned if you plan to read the entire poem, it transitions quickly into a graphic description of whale sex.) Kirk is the most passionate defender of the mission at hand: McCoy is ready to bail out at the first discussion of time travel, and while Spock’s sense of duty is intact, he is still recovering the memories that confirm his reasons for committing to these people. The entire crew, but Kirk most of all, is in an odd position of defending the planet and Federation that stand ready to convict them for crimes committed in Star Trek III. The Klingon ambassador calls Kirk a “renegade,” and it’s a fair description. Yet Kirk is also the example he needs to be, and has always been: giving up is never an option.

The entire crew is ready for the challenge. One of the great features of STIV is the meatier roles for the supporting cast: Sulu flies a Huey helicopter (“Huey” actually refers to a wide range of helicopter models produced by the former Bell Helicopter), Uhura and Chekov retrieve nuclear particles from the aircraft carrier USS Enterprise (which was, in fact, the world’s first nuclear-powered carrier), Scott “invents” transparent aluminum and creates a whale pen in the Bird of Prey, and McCoy rescues Chekov from brutal 20th century healthcare while helping an elderly patient grow a new kidney. Despite Kirk’s leadership, this is the 20th century, and Kirk is as out of his element as the rest of them. So it makes sense that everyone would have more substantial duties.

Somehow the film’s lighter tone balances well with the story’s literal earth-shattering stakes. Nimoy’s skillful direction has a lot to do with that. And Leonard Rosenman‘s score helps considerably: while some passages feel a bit dated today, particularly the hospital escape, Rosenman’s music reinforces all of the key moments, from the appearance of the probe to Chekov’s run through the aircraft carrier to the confrontation with the whale hunters. Rosenman already had serious science-fiction credentials, having composed scores for Fantastic Voyage (1966) and two Planet of the Apes movies.

The film’s environmental message is also delivered cheerfully enough that only the most extreme wingnuts would take offense. Of course, it’s absurd that we humans have separated ourselves from the “environment” (better known as “the world”), as if we are somehow superior to the very biosphere that sustains us. During the 20th century, hundreds of thousands of humpback whales were killed. The International Whaling Commission was established in 1946 and later began imposing regulations and moratoriums on whale hunting. Estimates vary widely, but the global humpback whale population seems to have grown from a low of 5,000 – 10,000 to over 80,000 today. In addition to ecology, we also get a bit of commentary on 20 century healthcare, which McCoy refers to as a “Dark Ages” practice relying on “butchers’ knives.” Televised Star Trek frequently engaged in social and ethical commentary, and the first three movies edged into this territory, so a “save the whales” premise shouldn’t surprise anyone. STIV even serves as something of a corrective to Star Trek‘s history of human superiority: only dual-species Spock could effectively communicate with these intelligent sea creatures. The probe is here for the whales, not for us.

As Star Trek III was the story of Spock’s rebirth, so STIV is also somewhat a story of rebirth. We have hopes now of a new humpback whale population. And in the end, the crew boards a brand new Enterprise. “My friends, we’ve come home,” Kirk says. Home, for them, is not earth, but the ship that will transport them to adventures. And, symbolically, “home” is the end of the Khan-Spock-whales trilogy and back to some good old-fashioned exploring reminiscent of the TV series. But while earth may not be this crew’s home, the film also reminds viewers that it is our home, and we can’t zoom off to settle on other planets if life here becomes unpleasant. Nicholas Meyer, who wrote the San Francisco portion of the script, preferred the story’s original ending: Gillian Taylor stays on 1980s earth, committed to ensuring the survival of humpback whales. Meyer’s argument, and I agree, is that the conclusion as filmed absolves us of responsibility for our own future. We can’t sit back and rely on technologically advanced saviors or a future generation. Star Trek has always encouraged a sense of duty, a commitment to society that transcends self-interest: the needs of the many outweigh the needs of the one. In his unpublished Whales and Men, Cormac McCarthy speculated that “Where are the whales?” might one day be an important question. In fact, the survival of whales, and the web of life they represent, is crucial today. Woe unto us if we ignore the lesson.

Next: The Final Frontier (1989)