During 2020 – 2022, I wrote a series of essays about every episode of Star Trek: The Original Series. I’m finally expanding the work to include the original cast motion pictures. This is a link to the TV series essays. If you’re reading this, I assume you have already seen Star Trek: The Motion Picture. Also, if you enjoy this essay, please share it on your favorite social media platform so others can discover my work.

“Voyager did things no one predicted, found scenes no one expected, and promises to outlive its inventors. Like a great painting or an abiding institution, it has acquired an existence of its own, a destiny beyond the grasp of its handlers.”

— Stephen J. Pyne —

— Voyager: Seeking Newer Worlds in the Third Great Age of Discovery —

Release Date: 7 December 1979

Director: Robert Wise

Composer: Jerry Goldsmith

Crew Death Count: 1 (This is a gray area that I address in the text; also the crews of Epsilon Nine and three Klingon ships are killed)

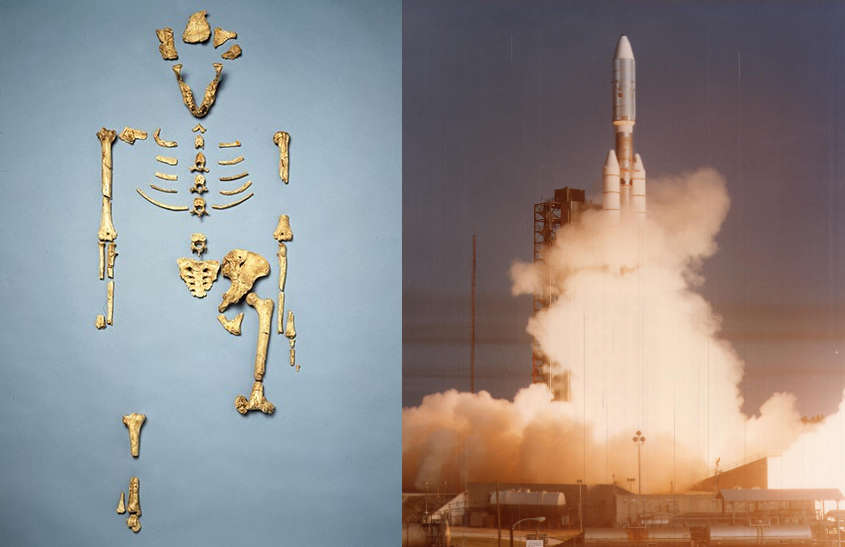

It has been ten years since we last saw NCC-1701 and her crew. During that time, U.S. viewers lived through the collapse of the U.S. phase of the Vietnam War (U.S. troop capacity peaked at 543,000 in April, 1969, only two months before TOS’ final episode, “Turnabout Intruder,” aired), Watergate, the 1973 oil crisis and subsequent recession, economic stagflation, a decline of the domestic labor movement, the recovery of fossil hominid Lucy in Ethiopia, a series of manned lunar landings, the Viking Mars landings, the launch of Voyagers 1 and 2, the beginning of the personal computer revolution, and a whole series of other events that situated humanity in a greater historic and interstellar context while simultaneously providing the fuel for Reagan/Thatcher conservatism and societal schisms that continue to widen decades later. If we ever needed a hopeful vision of the future, this was the time. Thankfully, Paramount Pictures, after a lot of waffling, agreed, giving us Star Trek: The Motion Picture (TMP) at the end of 1979.

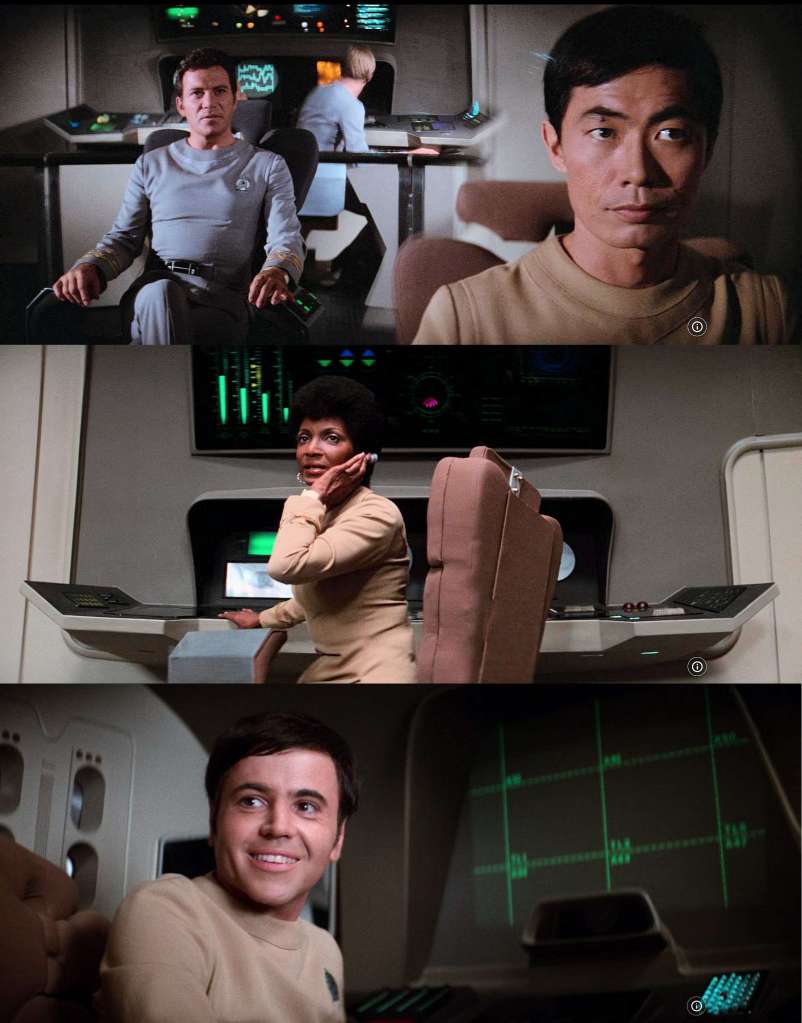

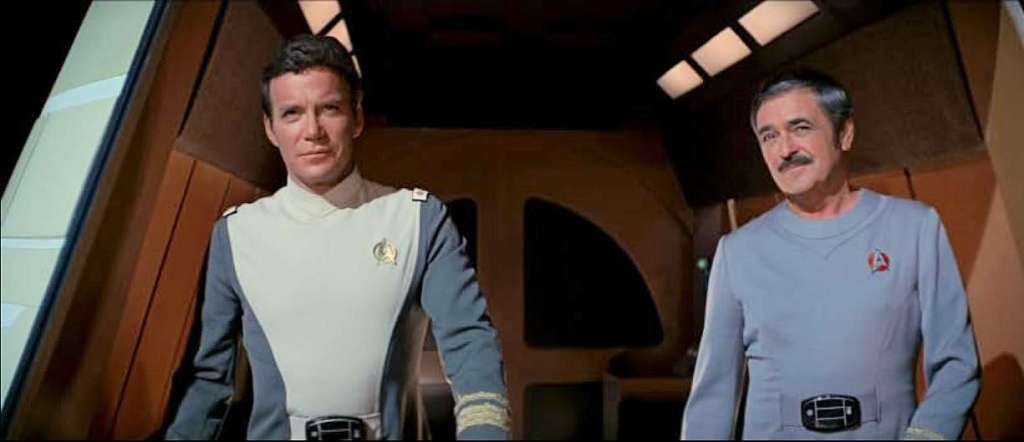

With blissfully little time catching up with what our heroes have been doing the past ten years – because these were the good old days when we didn’t need a steady IV drip of Easter eggs and origin stories – we jump into the action fairly quickly. An alien entity of overwhelming size and power is detected by the Federation when it (the entity) destroys three Klingon vessels and sets a course for Earth. By an astonishing coincidence, the newly overhauled USS Enterprise is the only starship close enough to intervene. Why the Federation doesn’t have stronger fleet capacity around its headquarters planet is never explained. Kirk, now an admiral and head of Starfleet Operations, quickly pulls rank and takes command of the untested Enterprise from her intended captain, Will Decker (Stephen Collins). Uhura, Sulu, Chekov, Scott, Chapel, and Rand (welcome back!) are already on board, along with new navigator Ilia (Persis Khambatta). Kirk drafts McCoy back in to service and pretty soon Spock shows up, so the old gang can unite to confront the entity, which calls itself V’Ger. V’Ger turns out to be the result of a merger between the earth probe Voyager 6 and an alien race of living machines. On a quest to learn all there is to know and join with its creator – destroying all “infesting” biological units in its way – V’Ger merges with Decker and an Ilia look-alike, transforming into an invisible version of the star child from 2001: A Space Odyssey.

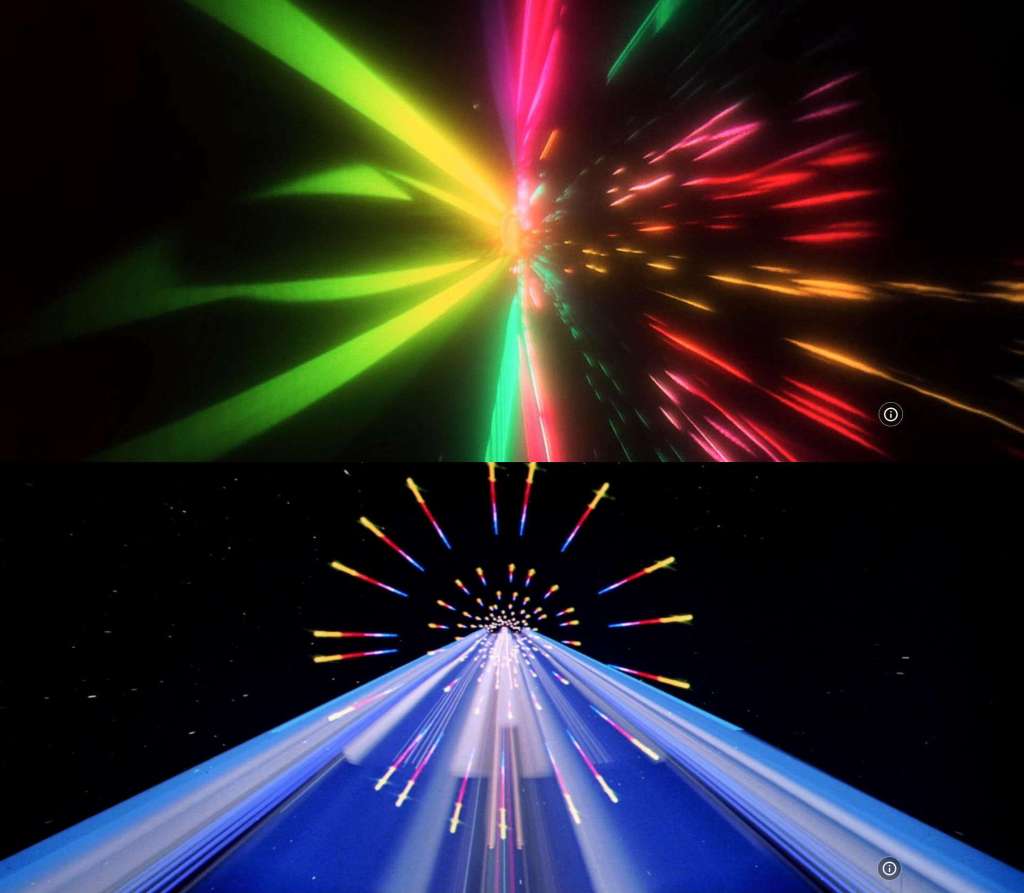

Let’s address that connection to s-f uber-classic 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), because this relates to TMP’s pacing, one of the prime complaints from buffoons discerning critics. 2001 clearly provided stylistic and conceptual inspiration for TMP, from the aforementioned pacing to the psychedelic V’Ger tour late in the film. While 1977’s Star Wars inspired Paramount to proceed at warp speed with a Star Trek movie, the final product’s mature, anti-Star-Wars pacing is something I appreciate even more over time. A lot of the thanks for this belongs to director Robert Wise. Wise already had a long, distinguished career, having directed science-fiction (The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951)), musicals (The Sound of Music (1965)), war movies (Run Silent, Run Deep (1958)), westerns (Blood on the Moon (1948)), noir (The House on Telegraph Hill (1951)), and just about every other genre. Run Silent, Run Deep is especially interesting for its premise of an officer pulling rank to take command of a ship from another officer. In hindsight, I can’t imagine Star Trek: The Motion Picture being directed by anyone other than Robert Wise.

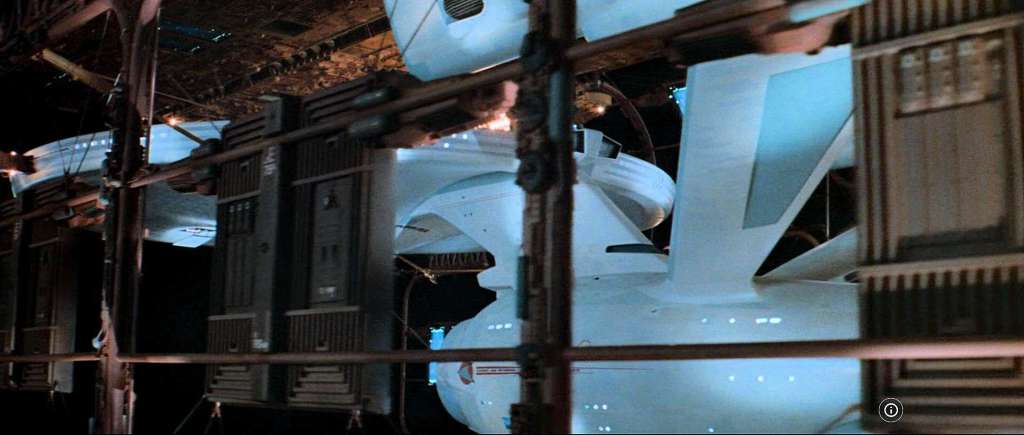

Another 2001 connection was Douglas Trumbull, who had worked on 2001 and who was recruited to handle visual effects for TMP after a disastrous false start with another VFX firm. Trumbull was particularly responsible for the majestic Enterprise unveiling scene some of you idiots contrarian viewers disapprove of. Trumbull specifically had 2001 in mind for that scene. This fan is always impressed with the enduring design of the Enterprise, and with the unveiling scene’s perfect combination of visuals and Jerry Goldsmith‘s music, it works quite well as a stand-alone short film. Another Space Odyssey influence was Spock’s spacewalk, with conceptual art by Robert McCall, who had designed posters for 2001.

The grown-up pacing means TMP takes its time bringing our characters together. That includes meeting the two primary new-comers, Decker and Ilia. Decker’s backstory didn’t make it into the final film but was described in the novelization by Gene Roddenberry: Decker was the son of Commodore Matt Decker (William Windom) from the second season episode “The Doomsday Machine.” In that episode, Commodore Decker was traumatized by the loss of his crew to a mysterious planet destroyer; he tried to seize command of the Enterprise on a quest for vengeance as a result. Does that event influence Will Decker’s experience of losing command to the Enterprise‘s former captain? Some of Ilia’s backstory is also muddled and probably not adequately explained: she is a Deltan, whose pheromones turn humans of the opposite gender to mush. Ilia also demonstrates healing abilities when Chekov is injured on the bridge. The Decker/Ilia romantic past was an inspiration for the Riker/Troi relationship in The Next Generation.

Another subject of frequent criticism is the opening scene, V’Ger’s encounter with three Klingon vessels. We don’t see the Klingons again for the rest of the movie, so what does the scene contribute? Most importantly, we have an immediate sense of V’Ger’s power. TOS established Klingons as the warriors of the galaxy and V’Ger absorbs three Klingon warships – they’re K’t’inga class cruisers, but civilians won’t know or care about that – without a struggle. V’Ger is clearly a serious threat. The fact that this results from the Klingon ships firing first offers guidance to the Enterprise crew later. We’re also reminded that the galaxy is not exclusively Federation territory; other cultures are impacted by these events. (As for Klingon anatomy, I don’t waste time debating bumpy foreheads. To quote Shatner Night Live: Get a life!) Finally, it’s significant that the Klingon vessels don’t explode. It may not be fully clear on initial viewing that the ships are being digitized and absorbed into V’Ger’s knowledge base; this is clarified in the Marvel Comics adaptation, but only implied during Spock’s spacewalk in the movie. We can even speculate that knowledge of Klingons and other cultures may have contributed to V’Ger’s relative belligerence.

One of my own criticisms of the movie is how little action the supporting cast sees. Uhura and Sulu are generally confined to their old TV roles. Chekov gets a hand zapped by V’Ger. Scott pilots Kirk to the Enterprise and gets a few moments to complain about the warp engine balance. Chapel, a doctor now, doesn’t get much dialogue but at least she has a presence in several scenes as a senior medical officer. And poor Yeoman Rand. No longer a yeoman now, but the transporter chief, Rand has the misfortune of beaming up the new Enterprise science officer when the transporter malfunctions with horrific results. (Grace Lee Whitney experienced a real-life horrific outcome after watching her TMP appearance, descending into a self-destructive spiral that took years to recover from.) The later movies, especially III – VI, developed the supporting cast much more effectively.

New-comer Ilia gets more action, but suffers the ultimate fate in being killed by V’Ger. Despite some implication that Ilia has somehow been reincarnated in the Ilia-probe, the probe spells out clearly when she boards the Enterprise: “That unit [Ilia] no longer functions.” The probe’s emotional displays late in the film seem more an outcome of V’Ger’s inexperience in designing carbon-unit reproductions. The character of Ilia – whether as herself or as the Ilia-probe – seems present primarily as an expression of Gene Roddenberry’s sexual preoccupations. Why else would she spend so much of the movie outfitted in a skimpy robe and stiletto heels? Heels! On a starship! From a story standpoint, the character is mostly present as a V’Ger interface and to provide heterosexual respectability to the Decker/V’Ger mating ritual. (More on that later.)

The remaining characters – Kirk, Spock, McCoy, and Decker – are individuals who have lost their way and need to figure out what they really need or want out of life. McCoy has perhaps the least clarity under this interpretation, primarily because his arc is resolved so early in the film. All we know about McCoy post-Starfleet is that he has retired and grown an impressive beard. He is plenty upset at being drafted back into service, and who can blame him? Starfleet has been presented as a noble undertaking in a future where humans live lives of their own choosing. The “reserve activation clause” used to conscript McCoy has sinister potential. How often is this clause invoked? This really deserves more attention. Still, after one pep talk from Kirk, the doctor embraces one of his most important roles from TOS: keeping Kirk in line. It’s almost as if Kirk recognizes the need to be saved from his own impulsiveness. Before we know it, McCoy intervenes in the Kirk/Decker feud to remind Kirk that he is essentially the bad guy in that dynamic. Tending to his friends is what McCoy really needed. This is possibly my favorite Leonard McCoy appearance in the feature films.

In this context, Kirk’s arc seems resolved early on, also. Now an admiral and Chief of Starfleet Operations, Kirk almost immediately achieves the straightforward goal of taking command of the Enterprise, convincing the unseen Admiral Nogura that his experience makes him a more qualified captain than Will Decker. Kirk explains this directly to Decker; clearly his intentions are noble. Aren’t they? Or is this purely an ego move for Kirk? Would James T. Kirk really jeopardize the earth’s population just to be a captain again? He certainly appears focused, obsessively reminding his crew of V’Ger’s approach. Yet Kirk needs help to find his way through the Enterprise corridors, symbolizing that he is lost both literally and emotionally. Only over the course of the mission, with McCoy’s guidance and Spock’s timely arrival, does Kirk truly settle back into starship command. The message will be explained more explicitly in Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan, but clearly Kirk needs to be in the center chair, whatever the psychological motive.

And what of this question of experience, the primary debate between Kirk and Decker early in the movie? Decker argues that his intimate knowledge of the renovated Enterprise entitles him to command. “You haven’t logged a single star hour in two-in-a-half years,” Decker tells Kirk, as hard as that is to believe. Whereas Kirk commanded the initial five-year mission, confronting the unknown, perhaps making him the ideal leader in the current crisis. Whose experience is more valuable in these circumstances? The movie’s answer: Kirk’s. Just watch the “V’Ger is a child” scene and Kirk’s response while Decker, who hasn’t been shy about offering suggestions, stands by quietly. This is the point when Kirk is fully in leadership mode.

So if TMP is essentially a story of individuals finding (or re-finding) their life’s purpose, and balancing those needs with the needs of the many, what does Decker really need? While occasionally chafing against Kirk’s leadership, he essentially falls in line quickly in his new role as executive officer and, for a short time, science officer. Was command of a starship really his top priority? Returning to his absent back story, as the son of Commodore Decker, it’s easy to imagine that Will Decker pursued command out of a sense of duty rather than true commitment. He essentially tells us that in the movie’s climax, as he and Ilia merge with V’Ger: “Jim, I want this. As much as you wanted the Enterprise, I want this.” In other words, starship command was not his true ambition. Decker and Ilia, by joining V’Ger in a quest for ultimate knowledge, are an inverse Adam and Eve, venturing out of the Garden of Eden with V’Ger as the tree of knowledge. Which returns us to the question of whether this is still the Ilia-probe or if the real Ilia has somehow been revived and inhabited the probe. Or is this somehow an expression of V’Ger itself taking on humanoid form?

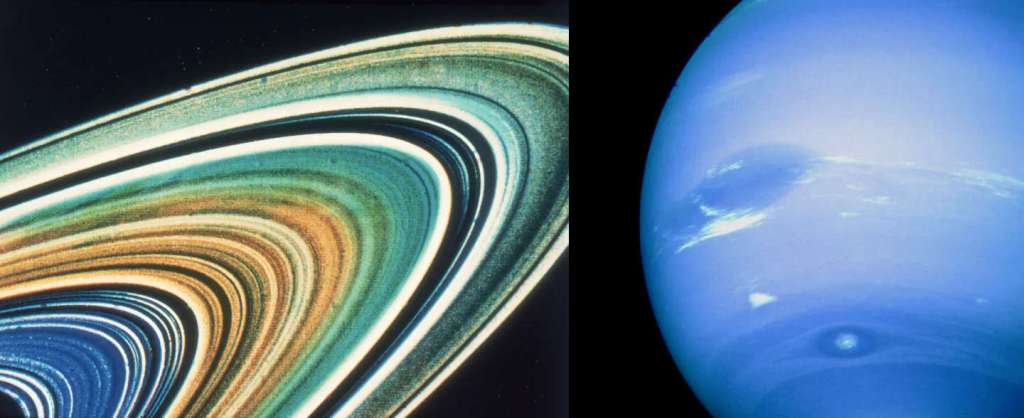

Just like the humanoid characters, V’Ger is also sorting out its true purpose after two or three centuries gathering knowledge across the universe. V’Ger is really Voyager 6, a 20th century earth probe, after a massive upgrade by an extraterrestrial species of living machines. Of course, there were only two Voyagers in real life, but in a better world there might have been more. By the late 1970s, human spaceflight objectives were largely reduced to earth orbital missions, but unmanned probes were dispatched across (and beyond) the solar system. The Planetary Grand Tour was devised in the 1960s when Jet Propulsion Laboratory engineer Gary Flandro noticed that a planetary alignment, occurring once every 175 years, would facilitate a gravity assist visit to multiple planets. The original plan called for four interplanetary probes, but Nixon-era budget cuts, motivated partly by defense industry support of the space shuttle program, resulted in only Voyagers 1 and 2 being launched in 1977. The two probes conducted historic flybys of Jupiter, Saturn, Saturn’s largest moon Titan, Uranus, and Neptune. Both probes continue to transmit data; Voyager 1 is the super-achiever of the pair, currently (as of July 2025) more than 15.5 billion miles from earth and traveling at 38,000 miles per hour.

Yet this is far surpassed by the fictional Voyager 6, supercharged to learn all that can be learned and return that knowledge to its creator. This is such a vague undertaking that even V’Ger is confused. How would one know when all the knowledge had been obtained? V’Ger isn’t even certain of the creator’s identity, and its disdain for “carbon-based” entities demonstrates a clear bias inherited from the living machine species. It all adds up to a muddled machine as confused as the living characters. “It knows only that it needs, Commander,” Spock tells Decker. “But like so many of us, it does not know what.” Gradually, V’Ger understands that it needs to keep evolving, hence the need for Decker and Ilia – V’Ger’s vast knowledge and power make organic life the last remaining path. Despite V’Ger’s disappearance into an unseen realm, the bottom line seems to be that V’Ger needed to be more human, and that somehow we improved V’Ger “out of our own human weaknesses,” which doesn’t entirely make sense.

Human exceptionalism was a frequent premise throughout the original series and has been something of a thorn in Star Trek‘s side at various times: Data in The Next Generation and Seven of Nine in Voyager are classic examples of non- or semi-humans striving to become more human. In a galaxy rich with intelligent life, reducing that life to human terms seems to limit our potential and defeat the entire point of exploration. This was a limit of “The Changeling,” the original series episode with several parallels to TMP. One significant difference between Nomad, from “The Changeling,” and V’Ger, is that Nomad was essentially the vanity project of one individual, whereas the Voyager program was a large group effort. V’Ger also has common ground with the Borg; while the Borg is a collective of individual units, both have achieved massive scope by assimilating knowledge and cultures in a quest for self-improvement. Contrast this with the Founders from Deep Space Nine, a powerful collective that has contempt for other life forms and demonstrates no interest in self-improvement. So if the movie’s final message, “The human adventure is just beginning,” seems narrow in scope, we can still appreciate its deeper significance: there was a mindlessness to V’Ger’s pursuit of knowledge solely for its own sake, and only the companionship of others – whether human, Vulcan, Deltan, or others – gives that knowledge meaning. Ironically, Voyager 6 started out with the same mission as the Enterprise crew – to explore, seek out, and boldly go, yet only Voyager has put its experience to intentional use.

That’s the lesson Spock learns from the mission. V’Ger is the entire reason for Spock’s presence in the story, and Spock gets the movie’s most substantial character arc. In this mission, Spock is the only true explorer in this band of explorers. We first find Spock on his home world, nearing completion of the Vulcan ritual of kolinahr, which is an elimination of all remaining emotions. In fact, Spock has presumably completed the kolinahr process at this point because he has reached the medal awards stage. This is very likely a greater challenge for half-human Spock than for a conventional Vulcan. Yet Spock is clearly not fully committed to kolinahr, because he backs out at the last minute after a signal from V’Ger, a reaching out for a kindred spirit – because V’Ger is equally confused about its true needs.

This sets up a dynamic between Spock and V’Ger that drives much of the crew’s progress in deciphering V’Ger’s behavior and intentions. While Spock’s motive is largely personal, he is the only one genuinely interested in learning about V’Ger as an entity rather than simply looking for the Achilles heel of an assumed enemy. That’s the motive for Spock’s trippy space walk that concludes with a mind-meld; a mind-meld between Spock and a machine would seem to be impossible, but the precedent was established in “The Changeling.” And this is one of the film’s most important scenes, because it not only gives insight into V’Ger’s nature, but concludes Spock’s quest for self-discovery. Spock understands now what he needed all along, and that was…to be more human. Sigh. This is a mixed blessing, because of the aforementioned flimsiness of a human superiority premise. Yet Spock is half-human and now fully accepts this as part of his life experience; when Spock says that V’Ger will have to deal with what McCoy calls “foolish human emotions,” Spock is really describing himself. The upside is that Spock is now committed to rejoining the Federation and becoming the individual we will meet at the beginning of Star Trek II: a compassionate captain and a thoughtful giver of birthday gifts.

Friendship was a common theme in the original series and TMP is no exception. Spock, Kirk, and McCoy drifted apart and suffered for it. They have figured out what they needed: the old camaraderie that sustained them through so many adventures. This, it seems, is the real reason Kirk craves command: not out of vanity, but so he can live in the midst of his friends, his true family. Now the team is back together and all is well. If anything, it was all too easy. Yes, it took an entire movie to get the trio securely back in their positions, but the casual exchange at the end betrays the stakes of the mission. Shouldn’t someone be interested in trying to contact the living machine species? Or figuring out what really happened to Decker and Ilia?

This lack of a grand purpose is TMP’s one true flaw. An earth probe merged with intergalactic entities, grew to obtain massive size and power, and nearly destroyed the earth before converting into a super-dimensional entity in tandem with two crew members. Spock calls it “possibly the next step in our evolution.” That should have outcomes greater than a simple metaphor of delivering a baby. The Day the Earth Stood Still, 2001: A Space Odyssey, the Borg attack at Wolf 359, all had impacts on the individual characters and the society at large. We waited so long for a big-screen Star Trek adventure and we deserved better than a rushed and incomplete wrap-up. Instead, for that, we will have to wait for the next Star Trek movie, when the consequences will be both personal and profound.

Next: The Wrath of Khan (1982)