During 2020 – 2022, I wrote a series of essays about every episode of Star Trek: The Original Series. I’m finally expanding the work to include the original cast motion pictures. This is a link to the TV series essays. If you’re reading this, I assume you have already seen Star Trek V: The Final Frontier. Also, if you enjoy this essay, please share it on your favorite social media platform so others can discover my work.

Release Date: 9 June 1989

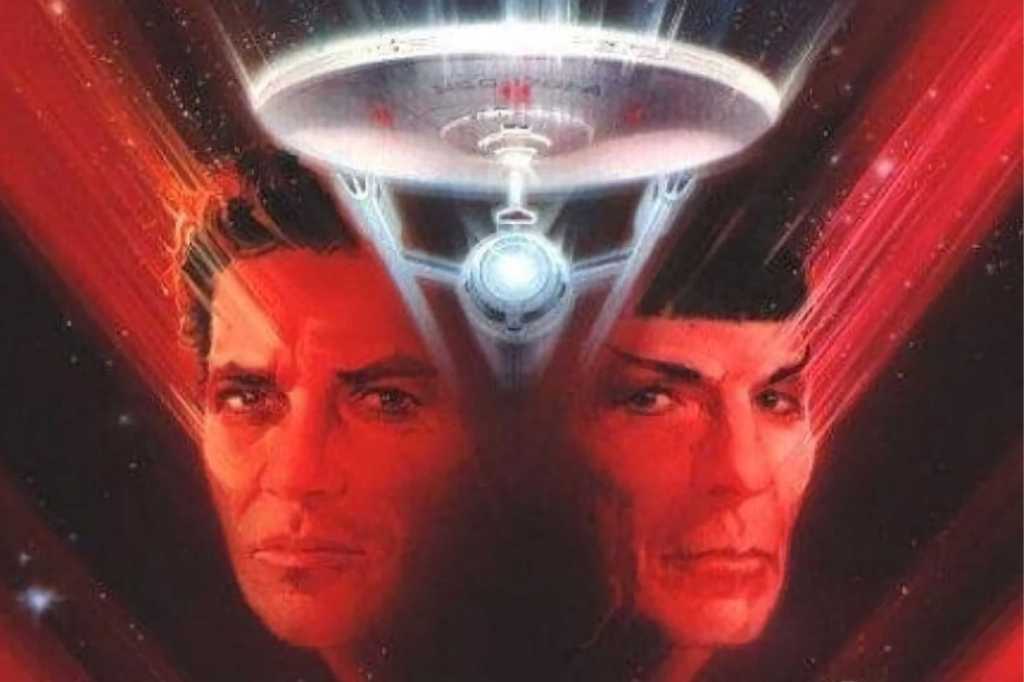

Director: William Shatner

Composer: Jerry Goldsmith

Crew Death Count: 0

“The will of God or the lunacy of man – it seemed to him that you could take your choice, if you wanted a good enough reason for most things. Or, alternatively, the will of man and the lunacy of God.”

–James Hilton, Lost Horizon—

Uh oh. We’ve arrived at “The Omega Glory” of the original cast Star Trek movies, Star Trek V (STV). Star Trek IV ended with the crew preparing for a shakedown cruise on the new Enterprise, NCC-1701-A, and Kirk urging, “Let’s see what she’s got.” Now the crew is on shore leave after that flight when a distress call is received from Nimbus III, where Romulan, Klingon, and Federation ambassadors have been taken hostage. Soon the religious zealot Sybok (Laurence Luckinbill), who is also Spock’s half-brother, has hood-winked the crew and hijacked the Enterprise on a quest to find God beyond the “Great Barrier” that surrounds the center of the galaxy. Yikes.

At the conclusion of Star Trek IV, as they approached the Enterprise A, Kirk told his crew, “We’ve come home.” In that light, STV opens with a prologue, following the format of the original series, that sets the stage for the adventure ahead. And the events in the prologue later result in a distress call that will tempt our crew into danger; this was another common technique of the original episodes. The Federation clearly has full awareness of the danger of responding to such distress calls; this is the entire premise of the Kobayashi Maru test introduced in Star Trek II. Sadly, a hint of misogyny was also an element of Star Trek’s original series, and STV doesn’t waste time. When asked what he seeks, Sybok keeps his response gender-specific: “What all men have sought since time began. The ultimate knowledge.” (Writing problems aside, Laurence Luckinbill’s performance is excellent.)

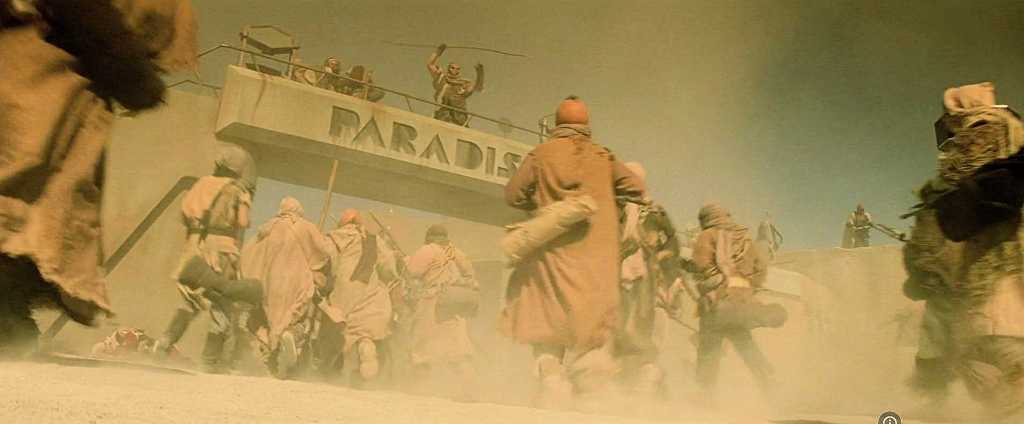

Another throwback to the original series, intentional or not, is “God’s” obsession with obtaining a starship in the belief that this will allow him (or it?) to conquer whoever it is that he wants to conquer. A similar purpose guided the plots of “And the Children Shall Lead,” “Space Seed,” “I, Mudd,” “The Omega Glory,” and “Wink of an Eye,” among others. Like the Genesis “torpedo,” starships represent the Federation’s extraordinary capabilities, and are intended as vessels of peace despite being seen as ships of war to much of non-Federation space. Yet this is the same Federation that has, apparently, produced a shoddy Enterprise-A; “I think this new ship was put together by monkeys,” according to Scott. (Still, it’s nice to see that a shuttle called Galileo remains in service.) And the Federation participated in the fumbled Paradise City on Nimbus III. What was the Federation’s real purpose with this project? The Federation, the Klingon Empire, and the Romulan Empire established Nimbus III as a “planet of galactic peace” and each sent a representative to the planet’s desert-like Paradise City. It appears that neither of the three superpowers have devoted sufficient time or resources to the peace endeavor.

The irony behind Paradise City’s name is clumsily obvious, and that level of obviousness is one of STV’s major flaws. Even the movie’s title, The Final Frontier, is too self-aware. However, the impossibility of utopian living was a recurring theme in the original series: “Maybe we weren’t meant for paradise,” Kirk told us in the Season One episode “This Side of Paradise,” an idea that would be revisited in multiple episodes. This same irony underlies Sybok’s quest for the mythical Sha Ka Ree, where he expects to find God and the ultimate answer to life, the universe, and everything. Even the God-entity, while clearly not an omnipotent creator, is able to see Sha Ka Ree for what it is, equivalent to humans’ uber-nostalgic Eden: “A vision you created.” STV would have been a better movie if it had spent more time exploring this idea and less time flying around in levitation boots. In real life, the name “Sha Ka Ree,” like the premise, is equally false. The name has no origin in myth or literature, but in casting ambitions – it’s a distortion of “Sean Connery,” the actor first sought to play Sybok. (Long-time franchise producer/writer Garfield Reeves-Stevens called it a nod to the equally mythical Shangri-La.) Desert-like Nimbus III is named with equal irony. A “nimbus” is another term for a halo or ring of light depicted around portrait subjects in paintings; it’s also the tail end of the name for rain-making cumulonimbus clouds.

For someone who claims to seek God and paradise, Sybok, like all cult leaders, lets nothing interfere with his own self-serving view of the world. His primary recruiting tactic is an abuse of the Vulcan mind-meld, which he describes as a means of sharing pain, relieving his followers of emotional trauma previously borne in isolation. Another of STV’s flaws, perhaps the most egregious, is the ease with which Sybok recruits members of the Enterprise crew. Even McCoy succumbs, and while the scene depicting the death of McCoy’s father is very touching, this weak-willed portrayal of the doctor and the other shipmates is not believable. Really, I’m not happy with McCoy’s role throughout the film. For example, the doctor’s early anger at Kirk for free-climbing El Capitan is justified, but his actual reaction is over the top, even for emotive McCoy.

In general, the characters seem written in an attempt at easy laughs rather than sensible character development. Sulu the navigator gets lost in Yosemite, LOL! Scott the engineer knocks himself out on a bulkhead in his own ship, ROTFLMAO! And the implied Scott/Uhura romance is entirely out of left field. Such scenes are flimsy and not worthy of both the actors and the characters they have developed for more than twenty years. One scene I’m still on the fence about, though, is Uhura’s fan dance to distract the horse wranglers. On the one hand, I’m not happy at seeing Uhura sexualized in a manner more fitting to 1960s America than the 23rd century galactic frontier. On the other hand, Nichelle Nichols was in her late 50s at the time, and it was refreshing to see some acknowledgement that women can be beautiful at any age.

The Klingons, perhaps, are portrayed more plausibly than our original characters. Captain Klaa (Todd Bryant) might come across as a bit of a parody, but he is equally reminiscent of a young and more impetuous version of Kruge from Star Trek III. It makes perfect sense that a young Klingon captain looking to prove himself would thrill at the hunt for one of the Genesis architects. Remember, the Klingon ambassador to the Federation told us in Star Trek IV, “There shall be no peace as long as Kirk lives.” Klaa’s decision, late in the film, to pursue Kirk in the shuttle rather than the Enterprise raises an interesting question: which has more symbolic value to a fundamentalist warrior culture, the ship or the individual who commands it? Clearly, Klaa chooses the individual, distinguishing him from the God-entity and the other systems-oriented villains who would choose the ship. He even offers to let the Enterprise and her crew go free in exchange for their captain. Klaa’s final decision, however, to yield to the old and forgotten General Korrd (Charles Cooper) with the claim that Klaa’s actions are not authorized by the Klingon Empire, seems out of character. Not formally authorized, perhaps, but it’s hard to believe the Empire would complain about the prize of James T. Kirk.

The earlier comment about time wasted on levitation boot stunts can be generally applied to the entire movie. There are some interesting ideas in STV that don’t get the attention they deserve. Why don’t these galactic explorers try to understand the true nature and origin of the God-entity? How did it become exiled in the center of the galaxy? Kirk at least has the sense to ask, “What does God need with a starship?”, which might seem superficial but still attempts to gain some useful information. Of course, the biggest question of all is never addressed, how Sybok could so easily turn Kirk’s crew against him, or the danger of the Vulcan mind-meld being used so perversely. It’s all as weak as Kirk’s justification for scaling El Capitan: “Because it’s there.” That seems to be the entire justification for making the movie

Does Kirk’s climb correlate to Sybok’s quest? (And why does Spock assume that Kirk is trying to set a record for free-climbing El Capitan?) Kirk climbs a mountain, Kirk rides horses, Kirk wears a “Go climb a rock” t-shirt: too much of STV feels self-aggrandizing, William Shatner’s attempt to promote himself as a hardy outdoorsman. Combined with Kirk’s implied moral superiority – only he and Spock resist Sybok’s charms – indicates the director’s over-sized vision of his character in relation to his numerous co-stars. Only Kirk’s well-written and compelling “I need my pain” speech saves the day. The film needs more such moments. What if we just call this mess of a film an extended dream sequence and move on?

After all, “Life is but a dream” is what Kirk and McCoy claim in the out-of-tune camp song scene, another premise that could have been connected to the quest for God – or paradise – but isn’t. (The moment also recalls Uhura’s classic line from Star Trek III: “This isn’t reality, this is fantasy.”) The Crew-Cuts sang “Life could be a dream” in 1954, but the so-called “dream argument” goes back as far as Plato. The French philosopher René Descartes generally gets the most credit for exploring the concept, but it also shows up in Eastern philosophy. When we dream, we’re not aware that we’re dreaming until after the fact. Some take this as evidence that we can never be certain about our sensory experience: if anything could be a dream, maybe everything is a dream. Of course, there is compelling evidence against the dream argument; for example, we don’t remember the beginning of dreams, as pointed out in Inception (2010), but we can generally trace every step that brings us to a given point in waking life.

Kirk’s belief that he will be alone when he dies lacks this waking life foundation – he has never hinted at this throughout the series or movies. His belief does, however, connect to one of Kirk’s motives for becoming a captain in the first place, as indicated in the previous movies: because he is happiest and most complete when in the midst of his friends. This is the camaraderie that has provided so much of the franchise’s foundation, and too much of this is lost in the easy cult conversion inflicted on McCoy and the others. Apparently, in an earlier draft of the script, Shatner wanted to go even farther in abandoning these old friendships. Leonard Nimoy and DeForest Kelley wisely refused. It would be dishonest to call STV anything but a disappointment, though Harve Bennett‘s claim that it “nearly killed the franchise” seems like an exaggeration; The Next Generation was nearing the end of its second season when STV was released. And the film isn’t a total disaster. STV raises questions worth asking, even if the answers are clumsy. The unhappy memories, the challenges in life, the disappointments, they’re all part of the journey. Those are the insights we carry with us to the next adventure. We still need our pain.

Next: The Undiscovered Country (1991)