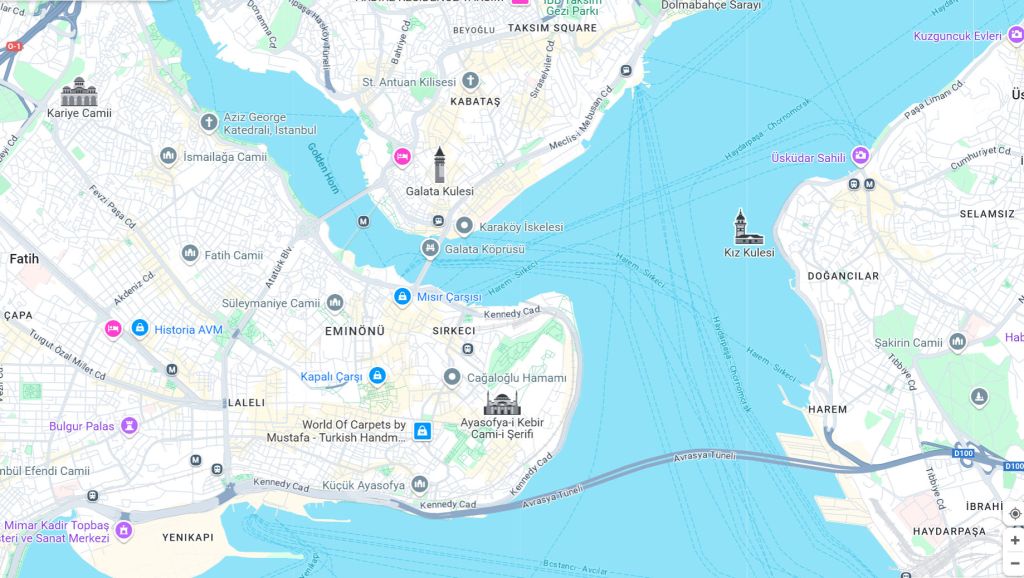

From Russia with Love (1957) was Ian Fleming‘s fifth James Bond novel. Like Diamonds are Forever, From Russia with Love was largely inspired by Fleming’s own travel experiences. In this case, as a reporter for Reuters, Fleming went to Moscow in 1933 to cover the trial of British engineers accused of spying. Then The Times sent him to Moscow in 1939 to observe a British trade mission. Later, reporting for the Sunday Times, Fleming went to Istanbul in 1955 to observe an Interpol conference. Many elements of the novel are based on actual people or events, such as the U.S. intelligence agent Eugene Karp, who was allegedly killed by Soviet assassins on the Orient Express while transporting documents disclosing the USSR’s knowledge of U.S. spy networks.

As with the previous Bond novels, this is my informal From Russia with Love reader’s guide regarding brand and place names, historic references, themes, and character development. A few references are repeated from previous books, in which case I’ve generally copied those entries. I haven’t include page numbers as this will vary by edition. I’m reading the Signet Books mass market paperback. Mr. Fleming was kind enough to divide his books into brief chapters, so references should be easy to find in the text. The best approach, if you can manage it, is to print this and keep it handy while you read the book. I’m only human, so if I’ve made any factual errors, please feel free to reach out to me via the Contact Me page.

Last updated 23 July 2025

Author’s Note:

For the first time, Fleming opens a Bond novel with his own message to the reader. In this case, he assures us that his descriptions of SMERSH, its headquarters, and General Grubozaboyschikov are all accurate as of the time of writing. The note is dated March 1956. We’ll elaborate on SMERSH and General G at the appropriate places in the text.

Part One: The Plan

1 Roseland

Dunhill:

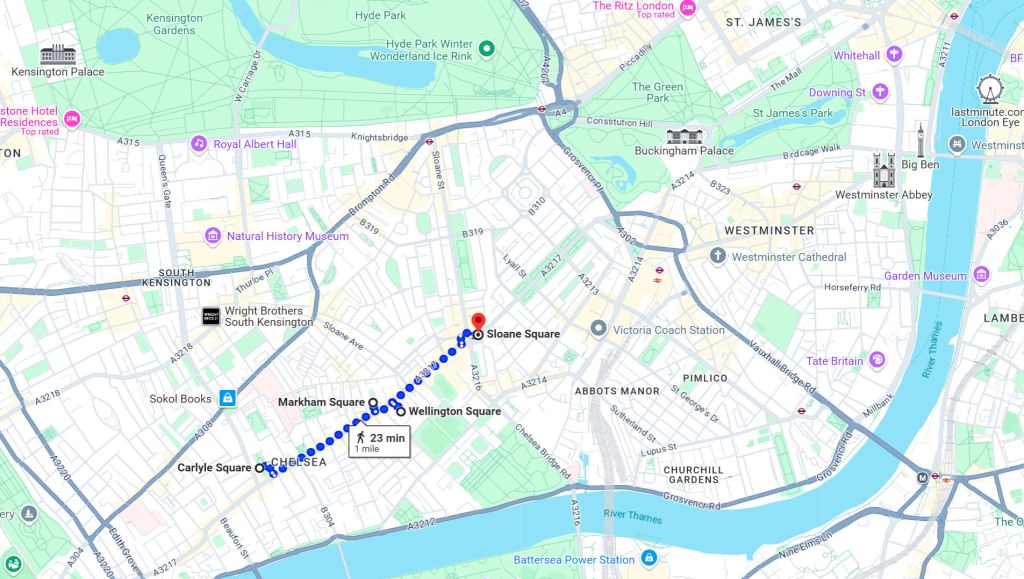

“The naked man” we see on page 1 has quite a trinket collection, a testament to his own vanity and the kinds of perks that might be within reach of a loyal Soviet agent. First, he has a Dunhill lighter. Alfred Dunhill (1872 – 1959) sold auto accessories in England in the late 1800s and early 1900s. After developing a pipe specifically designed for motorists in 1904, he opened a tobacco and pipe shop in London’s St. James‘s district in 1907. In 1921 Dunhill received a Royal Warrant to serve Edward, Prince of Wales. In 1924, Dunhill introduced the first lighter that could be operated with one hand. In the 1950s the company launched an early butane gas lighter. Alfred Dunhill Ltd. still operates today with menswear and leather goods among its product offerings.

Fabergé:

Our antagonist also owns a Fabergé cigarette case. The House of Fabergé was founded in Russia by Gustav Fabergé (1814 – 1894) in 1842 but it was Gustav’s son Carl Fabergé (1846 – 1920) who really brought the firm to prominence with the design of elaborate Fabergé eggs for the Russian Tsars. They made many other types of products, however, including the cigarette case pictured here from the early 1900s. After the October Revolution of 1917, the Fabergés attempted to recreate their business in Paris, but I’m guessing our Russian character is using a cigarette case from the company’s original success in Russia.

Wodehouse:

The naked man also has a copy of The Little Nugget by British author P.G. Wodehouse (1881 – 1975), published in 1913. I don’t fully grasp the significance behind Fleming choosing Wodehouse or this book in particular. Given the farcical nature of much of Wodehouse’s work, maybe this indicates how misguided the Russians are about English society. Wodehouse was interned by the Germans when they invaded northern France during World War II, where Wodehouse lived at the time. Upon his release in 1941, Wodehouse was “trapped” into participating in German radio broadcasts aimed at the U.S. and making light of the internment experience. Many in the U.S. and England considered Wodehouse a traitor after this, though he was cleared by both MI5 and MI6 at the end of the war. A number of British authors, including Sax Rohmer and George Orwell, defended Wodehouse, and perhaps this was Fleming’s attempt to do the same.

Girard-Perregaux:

Our man is quite the worldly figure. He wears a watch by Girard-Perregaux, the Swiss watch maker established in 1952 by Constant Girard (1825 – 1903). Based on the description, with windows displaying the date of the month and phase of the moon, the watch in question may have looked similar to the Vintage 1945 model shown in the photo. Girard-Perregaux manufactures watches today and is owned by the Sowind Group SA.

Summer in the USSR:

We’re told it’s June, specifically June 10. This is the fourth of the five Bond books published so far to take place in the summer months. Is summer the best time for secret agent work? Fleming wrote all of the Bond books at Goldeneye in Jamaica, where he went every year to escape the cold London winters. “The sun is always shining in my books,” Fleming once said.

Uncomfortable Villa:

The location is a villa with no bathroom and bars on the front windows along with an oak door. Are the bars to keep people out or in?

Masseuse:

She is not named and we will not see her again, but the masseuse is a useful character to give us a relative outsider’s perspective of the antagonist.

Roses:

The masseuse uses oil scented with roses, “as was everything in that part of the world…” We’ll learn shortly that the location is Crimea, a significant producer of roses and rose oil for scents and lotions.

Red Grant:

We finally learn the naked man’s name is Donovan “Red” Grant, known in the Soviet Union as Krassno Granitsky, code-named Granit. (Grant’s name is said to have come from a Jamaican river guide of Fleming’s acquaintance.) Fleming has employed two of his favorite tactics to define this villain:

- Grant has red hair; he has such “red-gold curly hair” that it’s in his name. Le Chiffre, Hugo Drax, and Shady Tree all had red hair.

- Fleming dehumanizes the character throughout the chapter: Grant is mistaken for food by a dragonfly, his eyes perk up like “animal’s ears,” he is described with such terms as “bestial,” “reptilian,” “a lump of inanimate meat,” “roast meat,” “pigginess,” and “morgue-like.” Perhaps most important of all, Grant is asexual, making him a distinct anti-Bond.

SMERSH:

Red Grant is the “chief executioner of SMERSH.” SMERSH, Smert’ shpiónam (“Death to Spies”), was a real Soviet agency. The name was created by Joseph Stalin (1878 – 1953), who became the dictator of the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death. SMERSH was only active from 1943 to 1946, when its activities were absorbed by MGB. Officially, SMERSH was charged with operations in the Red Army: counter-intelligence, counter-terrorism, and investigation of suspected traitors or deserters. The agency’s primary objective was to identify and eliminate alleged German spies operating within the Red Army during World War II. At one time, SMERSH was estimated to have recruited anywhere from 1.5 to 3.4 million informants within the Red Army (giving a sense of how large the army was). About 30,000 German “spies,” some actual spies but others perhaps not, are believed to have been killed as a result of SMERSH operations. It seems that Fleming’s portrayal of SMERSH was generally discredited in later years, particularly as it didn’t even exist after 1946. In the late 1960s, famous wingnut L. Ron Hubbard claimed that SMERSH had taken over governments throughout the world, and you can bet he had a complicated plan to defeat them.

MGB:

SMERSH is described as “the murder apparat” of the MGB. Ministry of State Security (MGB) was the Soviet Union’s secret police force from 1946 to 1953. The MGB was primarily an espionage and counter-espionage unit. They had a lot to do with keeping the post-war Eastern Bloc nations in line, but also infiltrated many aspects of Soviet life, including censorship and monitoring of public opinion. Between the end of World War II and Stalin’s death in 1953, the MGB arrested around 750,000 citizens, many of them for entirely political reasons.

2 The Slaughterer

Kharkov:

Ordered to Moscow, a guard speculates whether Grant’s flight will stop in Kharkov, also known as Kharkiv. Kharkiv is a city in eastern Ukraine that, in the late 1950s, had a population around 930,000. About one-third the distance from Crimea to Moscow, the city is an important regional transit hub. Tank construction was a significant element of the local economy before and after World War II. Civilians deaths and destruction of historic buildings occurred in Kharkiv during the 2022 Russian invasion but the city was later retaken by Ukrainian forces.

ZIS:

Grant is collected by a ZIS saloon. A “saloon” is simply a car with a closed body and a closed trunk separate from the passenger compartment. ZIS was established as AMO (Moscow Automotive Society) in 1916 and renamed First National Automobile Factory in 1925. It became Automotive Factory No. 2 Zavod Imeni Stalina (ZIS) around 1930. (Zavod Imeni = Plant Name) ZIS cars were typically used to transport Soviet heads of state and other VIPS, so much so that some roads had separate lanes specifically for those vehicles. In 1956, one year before From Russia with Love was published, Nikita Khrushchev changed the factory’s name to Zavod Imeni Likhachyova (ZIL), in honor of the facility’s former director and Central Committee member Ivan Likhachev (1896 – 1956). The specific car that picks up Grant may be the ZIS-110, produced from 1946 to 1958 and supposedly reverse engineered from a 1940s Packard.

Crimea:

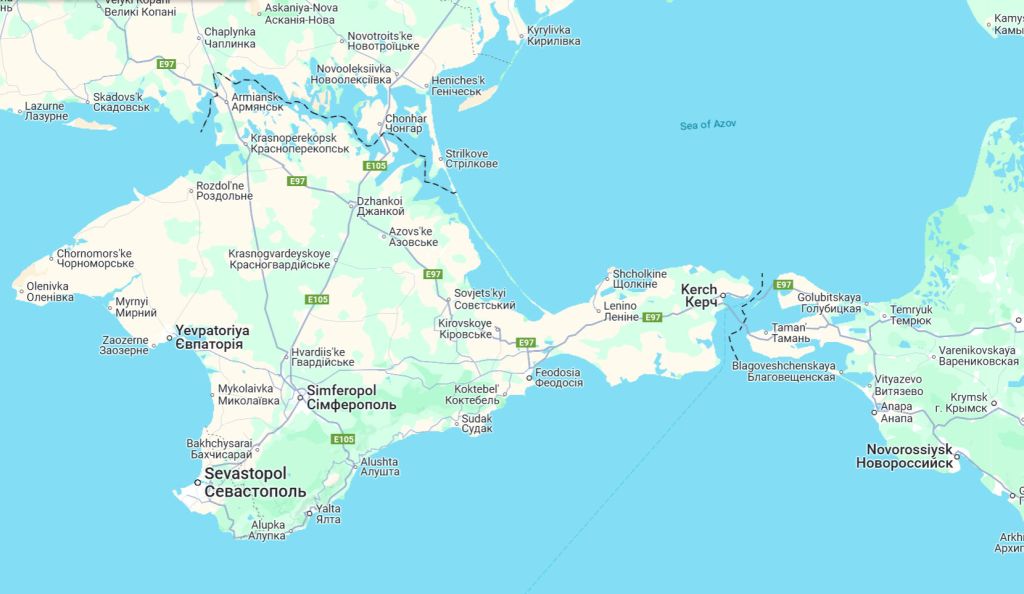

We finally confirm that Grant’s villa is in Crimea, the large peninsula south of Ukraine and surrounded by the Black Sea and the Sea of Azov. Except for the German occupation of 1942 – 1944, Crimea was a part of the USSR from 1921 until 1992, when it became Republic of Crimea, before being absorbed by Ukraine in 1995. We’re specifically in the “Russian Riviera,” known more commonly today as the “Crimean Riviera,” the region in southern Crimea of about 110 miles between Cape Aya in the west and Kara Dag Mountain in the east. The area is popular with tourists because of its scenic landscape, beaches, and moderate temperatures which must seem fairly warm relative to much of mother Russia. Fleming locates the villa specifically between Yalta – site of the 1945 Yalta Conference between the USSR, USA, and UK, and a popular Soviet vacation spot during the Cold War – and Feodosia, former site of Theodosia, founded by the Greeks in the 6th century BC.

Simferopol:

Grant is taken to the airport at Simferopol, the capital city of Crimea. An international civilian airport was located there in 1936 to begin regular flights to and from Moscow, though an actual concrete runway wasn’t completed until 1960. However, Grant flies out of the “military side” of the airport, and I think this refers to Gvardeyskoye airbase, actually located in the city of Hvardiiske, about 14 miles north of Simferopol. Russian air forces began flying there in the 1930s.

MiG-17:

Upon arrival at the airport, Grant observes a group of MiG-17 fighters landing, a reminder of the caliber of forces Grant is backed by. The Soviets began manufacturing the Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-17 subsonic fighter jet in 1952. The MiG-17 first saw combat in the Second Taiwan Strait Crisis in 1958 and was used with great success by the North Vietnamese during the Vietnam War. The competing American F-4 Phantom and F-105 Thunderchief were faster, but the MiG-17 had greater maneuverability. Later models with an afterburner could achieve speeds greater than 700 MPH. MiG-17’s are still in use by North Korea.

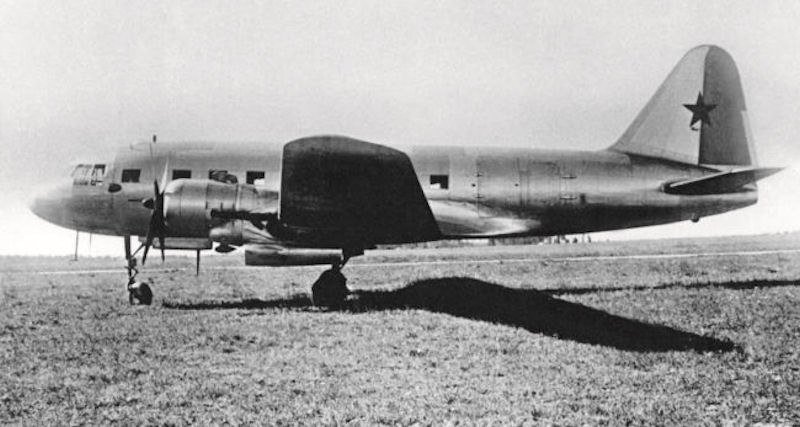

Ilyushin 12:

Grant flies to Moscow in an Ilyushin 12, which is likely the Ilyushin II-12. Ilyushin was a Soviet aircraft design and manufacturing bureau established in 1933 and still in operation in Russia. The II-12 was a twin-engine cargo and transport aircraft first flown in 1945. The military version of the II-12 carried three crew and up to 32 soldiers, but a civilian version used by the Russian airline Aeroflot carried up to 21 passengers.

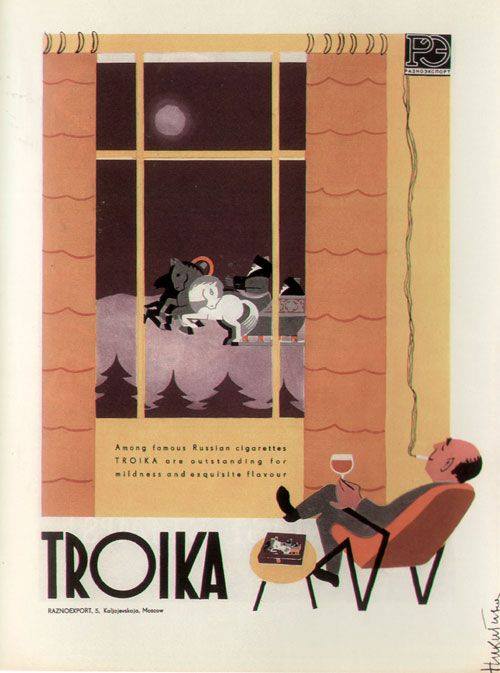

Troika:

Grant smokes a Troika cigarette. About all I can find on Troika is a post on the Russian social media site VK, reporting that Troikas were first produced in 1926 in Leningrad (now Saint Petersburg). Apparently Troika cigarettes were aimed at the lower economic classes but were also intended for export. Grant’s cigarettes contrast with the high-end cigarettes that are custom-made for Bond. However, considering Grant’s expensive lighter and cigarette case, why does he smoke cheap cigarettes? Should we assume that he doesn’t know the difference? Or is he trying to appear humble when meeting his superiors?

Aughmacloy:

We learn of Red Grant’s background, including his mother’s southern Irish heritage. Grant was born “in the small village of Aughmacloy that straddles the border…” I think Fleming is referring to Aughnacloy in County Tyrone in Northern Ireland, less than a quarter-mile from the border with the Republic of Ireland.

Puerperal Fever:

Grant’s mother died of puerperal fever shortly after his birth. Puerperal fever, or postpartum infection, is a generic term for a variety of bacterial infections that can occur in a mother’s reproductive tract within one to ten days of childbirth. If not contained, the infection can ultimately lead to septicemia and death. The term “puerperal fever” was used as far back as the 1700s and it caused the death of Mary Wollstonecraft, mother of Mary Shelley, in 1797. Some physicians recommended hygienic measures in hospital birth wards as a preventative as early as the 1840s, but these suggestions were ignored for decades.

Fists of Fury:

Even as a child, Grant is described as violent, and he took up boxing and wrestling while still in school. Does this imply that Grant takes after his German father, the professional weight-lifter? I can imagine Fleming, like many in England in the post-war years, had no love of Germans.

Sinn Féin:

Fighting at fairs brought Grant to the attention of Sinn Féin, which is Gaelic for “Ourselves” or “We Ourselves.” The political group was established in 1905 with the intent of forming a dual Irish-English monarchy, but by 1917 advocated an independent Irish republic. Like many political parties, Sinn Féin’s leadership and objectives changed over the years. In the late 1940s, the Irish Republican Army (IRA) essentially took control of Sinn Féin. In late 1956, soon after From Russia with Love was written, the government of Northern Ireland banned Sinn Féin in response to the IRA’s border campaign “Operation Harvest,” intended to unite northern and southern Ireland independently of Britain.

Full Moon:

After joining Sinn Féin, Grant began experiencing homicidal tendencies during the full moon. There is little credible research to indicate that a full moon affects mental health among the general population, though some research indicates that those with bipolar disorder can cycle more rapidly between depressive and manic states during the full moon. Historically, a full moon did appear to impact sleep cycles before the availability of exterior night-time lighting. Does Fleming intend to connect Grant to European mythology of werewolves? This would correlate with the animal qualities associated with Grant in Chapter 1.

Incomprehensible:

When killing women, Grant (thankfully?) sees nothing erotic in the act. He finds sexuality “incomprehensible,” further defining Grant’s character as the polar opposite of Bond.

Northern Ireland:

A serial killer by the age of 17, Grant found that “ghastly rumours were spreading round the whole of Fermanagh, Tyrone and Armagh.” All three are counties in northern Ireland, all on the border with the Republic of Ireland, and presumably the area where Grant was enacting most of his violence.

1945:

Fleming specifies that Grant turned 18 in 1945, making his birth year 1927.

Royal Corps of Signals:

At 18, Grant is drafted by England and serves in the Royal Corps of Signals, sometimes known simply as Royal Signals. Despite the benign sounding name, Royal Signals performs a combat function within the British Army and is often among the first to go into battle. During the post-war period, Royal Signals served in Palestine, Korean, the Malay Peninsula, and other locations.

Aldershot:

Grant was stationed in Aldershot, a town about 30 miles southwest of London. Partly as a result of the Crimean War, Aldershot Garrison was established in 1854, the British Army’s first permanent training camp. This led to a dramatic increase in the town’s population from military personnel and formal and informal institutions to support them. A considerable military presence remains today and the town is sometimes described as the Home of the British Army.

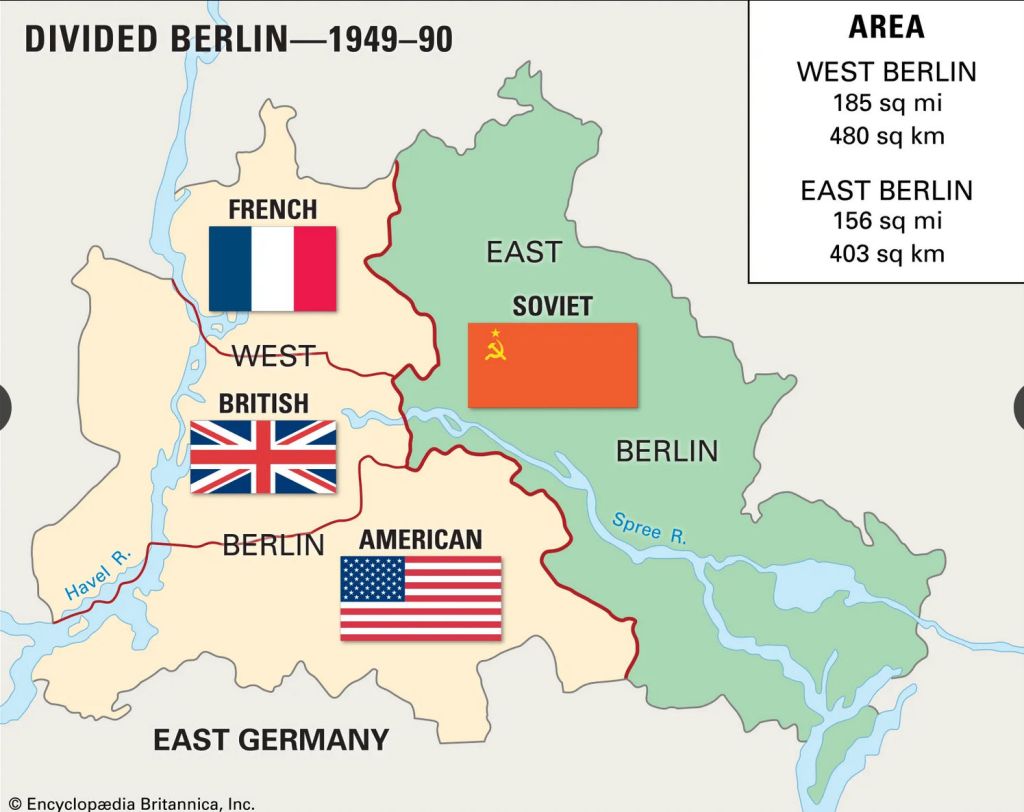

Berlin:

Grant was sent to Berlin, that iconic Cold War city, “about the time of the Corridor trouble with the Russians…” The division of Germany into Eastern and Western nations after World War II left Berlin deep in Soviet-controlled East Germany. The 1945 Potsdam Agreement divided the city into four sectors, three controlled by Western allies (U.S., UK, France) and the fourth controlled by the Soviets. The treaty did not, however, guarantee road or rail access to Berlin. With the long-term goal of uniting Germany under Soviet control, Joseph Stalin blockaded Berlin from Western access in 1948. The U.S. / British response was the Berlin Airlift from June 1948 through September 1949, delivering over 2.3 tons of supplies to East Berlin.

Russians:

His time in Berlin introduced Grant to “the Russians, their brutality, their carelessness of human life, and their guile…” This is in line with Grant’s own attitudes and incites him to defect. No mention of British cruelty in its own colonies.

B.A.O.R.:

Grant’s final incentive to defect is being disqualified for “foul fighting” during a B.A.O.R. championship. B.A.O.R. was the British Army of the Rhine, established in 1945 to administer the British zone of western Germany. Later it contributed to NATO in defense of West Germany from a feared Soviet invasion. B.A.O.R. had a troop strength of 80,000 in 1957. With the collapse of the Soviet Union, B.A.O.R. became British Forces Germany in 1994, which was itself largely disbanded in 2020.

Coventry:

After his boxing disqualification, Grant’s “fellow drivers sent him to Coventry…” This does not refer to the British city of Coventry near Birmingham. Instead, it is an English expression, “send to Coventry,” which basically means that Grant’s colleagues ghosted him.

Reichskanzlerplatz:

Grant defects after collecting outgoing mail from “Military Intelligence Headquarters on the Reichskanzlerplatz…” in what would have been West Berlin at the time. The square was laid out in the early 1900s with an U-Bahn rail station opened there in 1908. The name was intended to refer to Germany’s imperial chancellor (Reichskanzler) but was temporarily renamed Adolf-Hitler-Platz from 1933 to 1947. In 1963, the square was renamed Theodor-Heuss-Platz, in honor of Theodor Heuss (1884 – 1963), who was president of West Germany from 1949 to 1959.

What Year is This?:

Grant is said to be reflecting on these events ten years later. If this is ten years after the “Corridor trouble,” then the novel would have to take place around 1958. However, people much smarter than me estimate that the story would actually take place in 1954 or 1955 based on references to other historic events.

Perspex:

Grant notices his reflection in the plane’s Perspex window. Perspex was sold by the UK’s Imperial Chemical Industries. Polymethyl methacrylate, also known as acrylic glass, was sold by other companies as Plexiglass, Lucite, and various other trade names. It’s a relatively lightweight material with a higher impact strength than regular glass.

3 Post-Graduate Studies

Colonel Boris:

We won’t learn his name until later, but when Grant defects his initial questioning is conducted by the surly Colonel Boris.

Vorkuta:

Taking a dislike to Grant, Boris wonders “if it was worth while wasting food on him at Vorkuta.” Vorkuta is a Russian town located north of the Arctic Circle that primarily existed due to the discovery of vast coal reserves in 1930. This was followed in 1932 by Vorkutlag, a gulag (forced labor) camp. Coal mined by Vorkutlag inmates was vital to the survival of Leningrad during the 125-week siege of that city during World War II. The camp had a maximum of 73,000 prisoners in 1951, both Soviets and foreigners. A two-week inmate uprising at Vorkutlag in 1953 was ended with gunfire and the death of 66 inmates. The camp was closed in 1962. Vorkuta’s population plummeted after the collapse of the Soviet Union and privatization of the coal mines.

Dr. Baumgarten:

As a test of his conviction and ability, Grant is assigned to assassinate a Dr. Baumgarten in Berlin’s British sector. I can find no evidence that this is based on a specific actual event, though assassinations and attempted assassinations certainly occurred during the Cold War.

Kurfürstendamm:

Dr. Baumgarten is no slouch. He lives on Kurfürstendamm, sometimes described as Berlin’s equivalent to the Champs-Élysées. The boulevard was constructed over a log road built in the 1540s. During the 1920s, Kurfürstendamm became a popular nightlife area. After damage caused by air raids during World War II was repaired, Kurfürstendamm became one of the main commercial roads in West Berlin during the Cold War years. The boulevard has four lanes and runs a little over two miles.

Stalino, Etc.:

Grant observes a series of landmarks on his air journey to Moscow:

- Stalino, today known as Donetsk and located in Russian-occupied Ukraine (as of August 2024)

- Dnieper River, the longest river in Ukraine and the fourth longest in Europe, with several hydroelectric stations along the Ukraine segment

- Dnipropetrovsk Oblast, which the Dnieper runs through, a Ukrainian province with substantial agriculture, industry, and mining

- Kursk, site of the 1943 Battle of Kursk, the largest battle of World War II based on the quantity of troops and weapons involved

- Central Steppe, which I think is technically the East European forest steppe ecoregion, part of the Eurasian Great Steppe, the 5,000-mile region that has historically been a primary overland route between Europe and Asia

Manic Depressive Narcissist:

Grant is diagnosed by the Soviets as “an advanced manic depressive,” the condition of manic depression that is today referred to as bipolar disorder. This is consistent with his reaction to the full moon described in Chapter 2. The condition involves depressed periods alternating with elevated periods of mania. Self-harm, anxiety, and substance abuse have a higher than average correlation with bipolar disorder. To what extent this is a genetic or environmental condition is not fully known. It’s currently estimated that about 2% of the world’s population experiences bipolar disorder. Grant is also found to be a narcissist, defined as “an excessive preoccupation with oneself,” hardly a surprise based on our knowledge of him. (In case we’ve forgotten, we’re also reminded that Grant is “asexual.”) Finally, he has a high tolerance for pain. This is significant because Bond also has a high tolerance for pain and, to be honest, probably qualifies as a narcissist. But Bond is hardly asexual and, while a man of great passion, has too great a control over his mood and emotions to qualify as bipolar. Grant is Bond’s equal on paper, but lacks Bond’s connection to the substance of the human condition.

Two Biggest Purges:

Fleming writes about the use of violence to retain political power in the USSR, citing “the two biggest purges” in which “a million people have to be killed in one year…” Joseph Stalin conducted several purges of the Communist Party; one of them, the Great Purge conducted from 1936 to 1938, became violent. Guilt of the victims was predetermined – if the accused confessed to offenses, that proved they were guilty, and if they claimed innocence, that was exactly what a guilty person would do. About one-third of the members of the Communist Party were either executed or sent to gulags. Official figures cited nearly 700,000 executions and 116,000 dead in labor camps. I believe the other purge Fleming refers to might be the so-called Red Terror of 1918 – 1922. The Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin (1870 – 1924), took control of Russia in 1917 and undertook a program of political repression and executions to consolidate power after an assassination attempt on Lenin and assassinations of two senior members of the Bolshevik secret police. Estimates of casualties in the Red Terror vary widely, anywhere from 50,000 to 200,000 executions, with hundreds of thousands more deaths occurring in prisons.

Otdyel II:

Grant is referred to SMERSH Otdyel II, or Department 2, “in charge of Operations and Executions.” According to Wikipedia, this was the real function of Otdyel II: “Counterintelligence Operations within foreign POWs, and also filtering of Soviet armed forces officers and servicemen who had been POWs. … Also collection of intelligence information from areas immediately behind enemy lines…” Former POWs were not exactly welcome, as Stalin had declared surrender to be a traitorous act.

Leningrad:

Grant is sent to the Intelligence School for Foreigners outside Leningrad. Established as St. Petersburg by Tsar Peter the Great (1672 – 1725) in 1703, the city was renamed Leningrad in 1924 and reverted to Saint Petersburg in 1991. Based on the timing, perhaps Grant was in Leningrad during the 1949 – 1952 Leningrad Affair, orchestrated by Stalin to consolidate power and remove those who he might have considered disloyal. Six city officials were executed and 200 were sent to prison; their families were banished from living in any major city, essentially forcing them into Siberia. Two thousand more individuals were exiled from the city with their homes and property confiscated. I can find no information on an Intelligence School for Foreigners in the Leningrad area.

Kuchino:

Grant is sent to Kuchino, a small town south of Moscow, to attend the School for Terror and Diversion. According to this article at the Fleming’s Bond site, such a school actually existed, and apparently they really did produce the “explosive cigarette case” Grant mentions late in the book. According to the same article, Colonel Arkady Fotoyev was the school’s supervisor, as described in the novel. This passage also mentions Lt. Colonel Nikolai Godlovsky, “the Soviet Rifle Champion.” According to this article at the web site of British author Jeremy Duns, Godlovsky existed as described and Fleming probably learned about him from the 1950 book SMERSH by a former British agent named Edward Spiro.

Rubles:

In 1953, Grant receives “a handsome 5000 rubles per month.” According to Wikipedia, the Soviet ruble in 1953 was equivalent to about $0.25 USD, so Grant was receiving approximately $1,250 USD / month. $1 USD in 1953 is equivalent to about $11.78 as of August 2024, making Grant’s salary a whopping $14,725 / month in 2024. That seems hard to believe; someone please correct me if they find an error with this.

Tushino Airport:

Grant’s plane approaches Tushino Airport outside Moscow. Tushino was a small town just to the north-northwest of Moscow which was incorporated into the city of Moscow in 1960. Tushino Airfield was a general aviation airport where military exercises showcasing the USSR’s technological superiority were held in the Cold War years. The airfield has since been replaced with Lukoil Arena, a sports and entertainment facility.

4 The Moguls of Death

Sretenka Ulitsa:

SMERSH headquarters is located at 13 Sretenka Ulitsa (ulitsa = street in Russian). Sretenka Ulitsa runs roughly north-south inside the Garden Ring, the circular road around central Moscow that follows the course of the protective ramparts that surrounded the city in the 1600s. Supposedly a reader sent Fleming a photograph of this address after From Russia with Love was published, demonstrating that the site was not at all the way Fleming described. If I’ve interpreted the maps correctly, at the time of this writing (2024) the supposed location of SMERSH headquarters is a construction site in progress but was a parking lot in recent years.

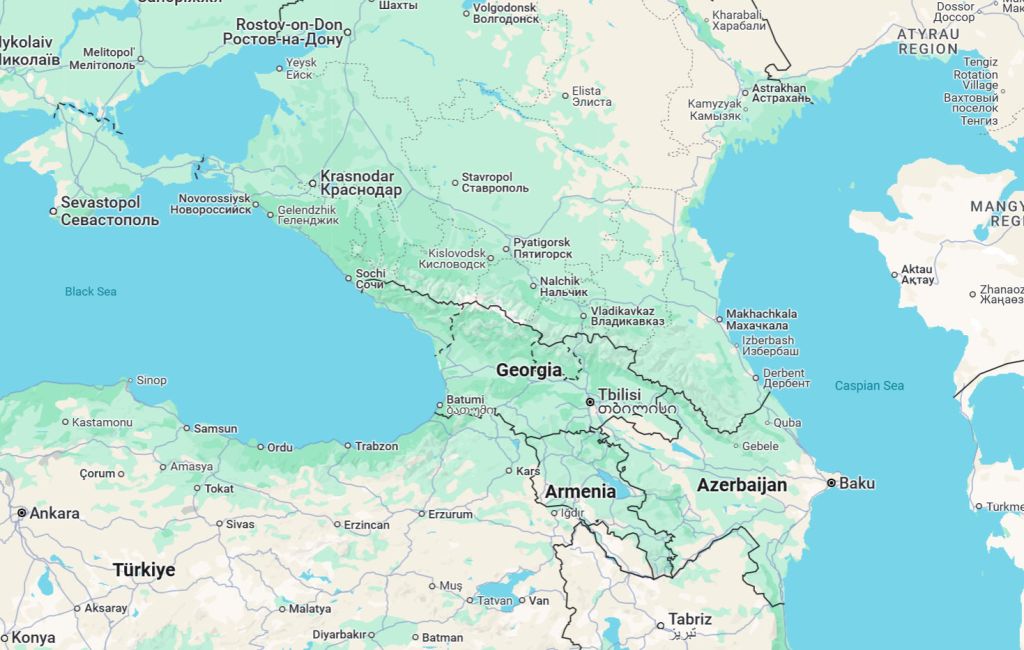

Caucasian Carpet:

The important second floor office where SMERSH planning is conducted has a Caucasian carpet. This would be an area rug from the Caucasus region between the Black Sea to the west and the Caspian Sea to the east. It appears that such textiles have been created in that region since the Bronze Age, prior to 2500 BC. The Caucasus Mountains form something of a geographic barrier between western Asia and eastern Europe. Numerous cultures with different languages have historically existed throughout the region.

Stalin, Lenin, et al:

Four framed photographs hang on the walls in the SMERSH conference room:

- Joseph Stalin (1878 – 1953), leader of the Soviet Union from 1924 until 1953

- Vladimir Lenin (1870 – 1924), a leader of the Bolshevik revolution and the leader of post-revolution Russia from 1917 to 1924

- Nikolai Bulganin (1895 – 1975), Soviet Minister of Defense 1953 – 1955 and Soviet Premier 1955 – 1958

- Ivan Alexandrovich Serov (1905 – 1990), NKVD (intelligence and state security ministry) Deputy Commissar 1941 – 1954, KGB Chairman 1954 – 1958, and later head of the GRU, the foreign military intelligence agency. We’re told that Serov’s photo was added on January 13, 1954, to replace that of Lavrentiy Beria (1899 – 1953), head of the NKVD 1938 – 1946 and, briefly in 1953, head of the MVD (Ministry of Internal Affairs) and first deputy premiere of the Soviet Union until being replaced in a coup led by Nikita Khrushchev. Beria was also one of the lead perpetrators of the Great Purge (Chapter 3) and was later suspected of having poisoned Stalin; Beria was executed in December 1953. I can find so special significance of the date January 13, 1954, as Serov took over the KGB in March of that year.

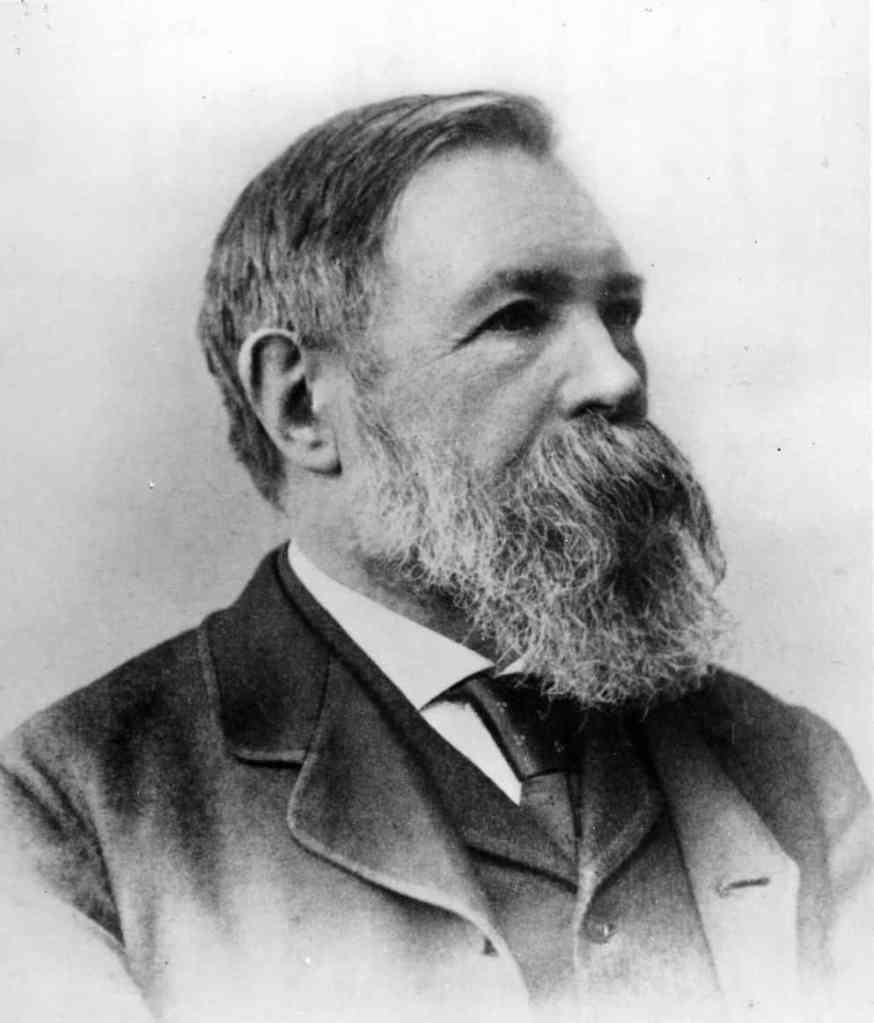

Marx, Engels, et al:

A bookcase in the SMERSH meeting room contains books by Marx, Engels, Lenin, and Stalin. Karl Marx (1818 – 1883) was a German jack-of-all-trades (philosopher, economist, historian, sociologist, and more) who published the pamphlet The Communist Manifesto in 1848 and Das Kapital, published in three volumes between 1867 and 1894. Marx predicted that class conflict created by capitalism would lead to socialism, and all these years later we’re still waiting. Friedrich Engels (1820 – 1895), like Marx, was a German-born multi-disciplinary thinker. He was a friend and collaborator with Marx, co-wrote The Communist Manifesto, and published numerous other works both alone and with Marx. Lenin and Stalin published their own works on political and economic theory, including Imperalism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism (Lenin in 1917) and On Questions of Leninism (Stalin in 1926).

General Grubozaboyschikov:

The head of SMERSH, in the novel, is General Grubozaboyschikov. Despite Fleming’s Author’s Note, I can find no evidence that “G” was a real person. The fact that the head of MI6 is M and the head of SMERSH is G is further evidence that this isn’t just a story of Bond confronting his own doppelgänger, but of the conflict between two equivalent but diametrically opposed cultures. G is later described as being an opponent of the late Lavrentiy Beria.

Medals and Ribbons:

Fleming cites a long list of medal ribbons worn by G. There is no need to repeat the list here, but it’s significant that G’s honors are not just from within Russia or the Soviet Union. He also wears the American Medal for Merit and a British CBE. The Medal for Merit was specifically created to honor civilians, including select foreign citizens, for distinguished service during World War II; it was last awarded in 1952. The Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire (CBE) was established, along with other rankings of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire, by King George V in 1917 to recognize those who “render important services to Our Empire.” CBE falls between KBE (Knight / Dame Commander) and OBE (Officer). It’s a reminder of Russia’s role in World War II and the fact that Russia was an ally with the U.S. and England during the war.

Praesidium:

G inquires about a meeting of the Praesidium (Presidium) that morning. The Presidium of the Supreme Soviet was the collective head of state of the USSR, its members chosen by both houses of the Supreme Soviet, the USSR’s primary legislative body and its only collective branch of government. The Presidium had 39 members and the chairman was sometimes described outside the USSR as President of the Soviet Union. It was headquartered in the Kremlin in Moscow.

RUMID:

G is about to meet with RUMID, GRU, and MGB. GRU and MGB have been mentioned previously. I can’t find any real substance on RUMID, but later we’re told that it is the intelligence department of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Khokhlov:

G says, “We do not want another Khoklov affair.” I’m not sure of the significance of Fleming’s spelling, as contemporary sources spell it Khokhlov. Nikolai Khokhlov (1922 – 2007) was a KGB officer whose father was assigned to a penal unit during World War II because of remarks about Stalin that were considered inappropriate. The father died during that service, and Khokhlov’s stepfather died in combat in 1941. As an NKVD agent during World War II, Khokhlov parachuted into Belarus, then occupied by the Nazis, and took part in the 1943 assassination of the violent and severely anti-Semitic German officer Wilhelm Kube. Khokhlov was so beloved at the time that he was the subject of the 1947 Soviet film Secret Agent. Khokhlov was sent to Frankfurt, in West Germany at the time, to assassinate Georgiy Okolovich, chairman of the anticommunist group National Alliance of Russian Solidarists. Khokhlov’s wife talked him out of carrying out the order, and while in Frankfurt Khokhlov defected to the West. Part of the “loot” Khokhlov brought to make his defection appealing were cigarette cases containing concealed handguns, which perhaps inspired Grant’s gun-toting book in the final chapters. The KGB attempted to poison Khokhlov in 1957 but he survived. It’s a fascinating story and one that many readers in 1957 would have at least heard of. Within the context of the novel, the “Khokhlov affair” is important enough to be repeated several times as a major embarrassment to the USSR.

Slavin, et al:

The heads of the various agencies arrive for their meeting with G: Lt. General Slavin (GRU), Lt. General Vozdvishensky (RUMID), and Colonel Nikitin (MGB). As far as I can tell, these are all fictional characters, though Fleming did have a tendency to base his characters on real people.

Moskwa-Volga:

G smokes a Moskwa-Volga cigarette. I can find nothing on this brand, however it is mentioned in Olen Steinhauer‘s novel Liberation Movements.

Zippo:

Despite smoking Russian cigarettes, G uses a Zippo lighter. Perhaps acquired during war-time service? Or, worse, confiscated from a captured U.S. spy? Most Zippo lighters have been manufactured in the U.S. since 1933. They were especially popular with the U.S. military during World War II.

Hard-Soft:

G describes a complicated, but admittedly compelling, change of Soviet policy toward its foreign adversaries. The previous hard policy “built up tensions” to the point of nearly provoking a nuclear exchange. The USSR has now, according to G, moved to a hard-soft policy, a nearly passive-aggressive approach of alternating between “the stick and the carrot.” This has the effect of confusing and destabilizing the Western powers in terms of foreign policy. From what little I’ve read of Khrushchev, I can easily imagine this being his brain-child.

Those Crazy Americans:

While discussing the transition from hard to hard-soft policy, G describes Americans as “unpredictable” and “hysterical,” which is hard to dispute. This hysterical nature was part of the Soviets’ motive for transitioning to the hard-soft policy.

Radford:

G claims that one of the U.S. hardliners who benefited from the hard policy was “the Pentagon Group led by Admiral Radford.” Arthur Radford (1896 – 1973) was a naval officer who, during World War II, supported recruiting women into the armed services, though in strictly low-level support positions. The Naval Reserve’s WAVES (Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service) program was a result. Radford served in a number of high-profile positions, always advocating for aggressive military policies, including increased reliance on “strategic” nuclear weapons in President Eisenhower’s “New Look” policy. Radford was Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff from 1953 to 1957.

Quemoy and Matsu:

G specifically mentions a hard policy when “China threatens Quemoy and Matsu.” Quemoy (also known as Kinmen) and Matsu are islands situated on the Taiwan Strait and the East China Sea, respectively. The Taiwan Strait separates Taiwan from mainland China and was the site of several conflicts between the People’s Republic of China and the Republic of China. Saying China “threatened” the islands seems like a tame description. PRC forces bombed Kinmen in 1954 – 1955. PRC forces also took control of parts of Matsu in 1953. Bombing of both areas in 1958 helped instigate the Second Taiwan Strait Crisis.

“India and the East”:

G mentions “Comrades” Bulganin and Khrushchev and Serov visiting India and the East so they could “blackguard the English.” Bulganin and Serov were both mentioned earlier in the chapter. Nikita Khrushchev (1894 – 1971) succeeded Bulganin as Premiere of the Soviet Union. Bulganin and Khrushchev traveled to India, Burma, and Afghanistan in late 1955. I can find no indication that Serov traveled with them. India and Burma (now Myanmar) had just become independent from Britain in 1947 and 1948, respectively. The British had tried to conquer Afghanistan more than once as a buffer between Europe and Russia. So a friendly visit from Khrushchev and Bulganin – where they “were warmly welcomed by officials and by the population of these countries” – might not have been viewed favorably by the British.

Global Playing Field:

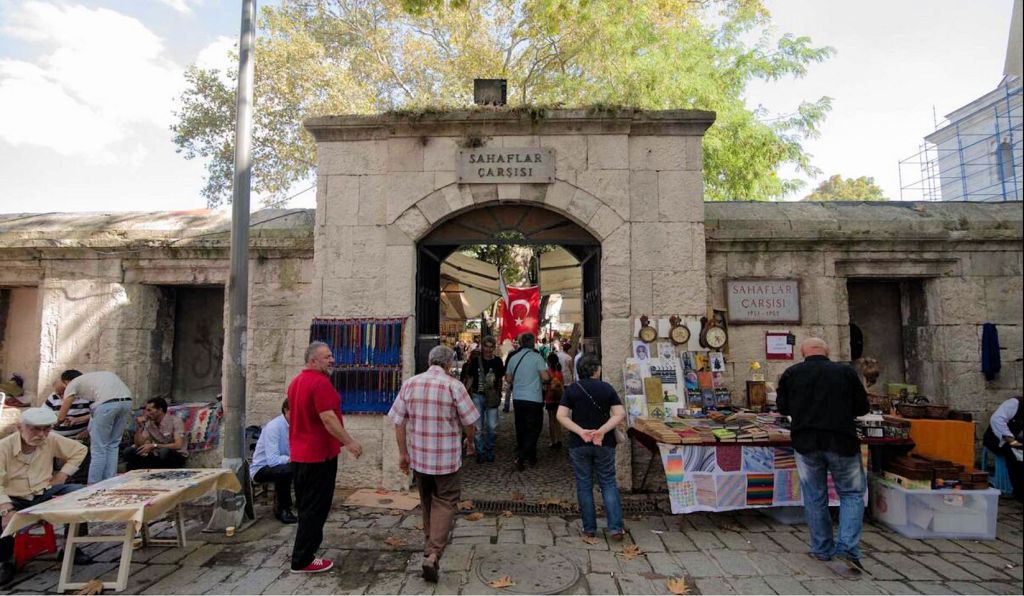

G cites a series of countries subject to Soviet intervention, both overt and covert: Morocco, Egypt, Yugoslavia, Cyprus, Turkey, England, France. It’s an indication of how much the Cold War affected every part of the globe.

Gouzenko:

Confessing Soviet intelligence failures as motivation for the current SMERSH conspiracy, G mentions “Gouzenko and the whole of the Canadian apparat and the scientist Fuchs…” Canada was considered important in terms of Soviet espionage even before World War II because of the country’s close ties with the U.S. and Britain. The Soviets developed an entire spy ring overseen from the Soviet Embassy in Ottawa. Igor Gouzenko (1919 – 1982) was a GRU cipher clerk sent to Ottawa in 1943. Gouzenko enjoyed living in Canada so much that, when he was about to be recalled to the USSR in 1945, he made off with a collection of secret documents and defected. (The Canadian government’s bungling of his defection reads like a bad comedy.) Information provided by Gouzenko helped the Canadians dismantle the entire spy network, including Klaus Fuchs (1911 – 1988), a German physicist who provided the Soviets with information on the Manhattan Project. Fuchs was actually in Britain, though he had been in an internment camp in Canada in 1940. For his spy work he was imprisoned in Britain for nine years.

The American Apparat:

Continuing his recitation of intelligence failures, G says, “then the American apparat is cleaned up…” I’m not certain, but I believe this refers to the Golos and Silvermaster spy networks, both exposed in 1945 by Elizabeth Bentley (1908 – 1963), a U.S. citizen recruited by the NKVD who later turned herself in to the FBI out of fear of KGB assassination. Ukrainian Jacob Golos (1889 – 1943) was a founding member of the Communist Party of the U.S.A. and was involved in falsifying documents to assist Soviet intelligence agents in taking up residence in the U.S. Nathan Silvermaster (1898 – 1964) served on the U.S. War Production Board during World War II and operated a network of Soviet agents within the U.S government.

Tokaev:

Before again mentioning the Khokhlov affair, G says, “then we lose men like Tokaev.” Grigory Tokaev (also known as Grigory Tokaty) (1909 – 2003) was a Soviet rocket scientist. Tokaev was a loyal communist but became disillusioned with Stalin’s government and, after being stationed in Berlin at the end of the war, defected to England. He later taught at The City University in London and helped circulate anti-communist propaganda.

Petrov:

Finally, G talks of “Petrov and his wife in Australia.” Vladimir Petrov (1907 – 1991) was a KGB officer stationed at the Soviet embassy in Canberra. His wife, Evdokia Petrova (1914 – 2002) was an NKVD officer also stationed at the embassy in Canberra. Petrov had been appointed by Beria; after Beria’s execution, he feared that he might be next. He defected to the Australian government in 1954. Oops, he didn’t bother to tell his wife and planned to leave her behind. Petrova was on a plane, being taken aback to the USSR by the KGB. When the plane stopped for refueling at Darwin in northern Australia, Australian officials offered her asylum and rescued her. The USSR recalled its embassy staff in Canberra and sent Australia’s embassy staff in Moscow back home.

5 Konspiratsia

Moujiks, Knout:

After G’s tongue-lashing, he thinks, “The moujiks had got the knout.” A “moujik” refers to a Russian peasant, primarily born before 1917, as everyone in the room certainly was. A “knout” was a type of whip made of leather thongs. While it could be used on cattle, its primary use was corporal punishment.

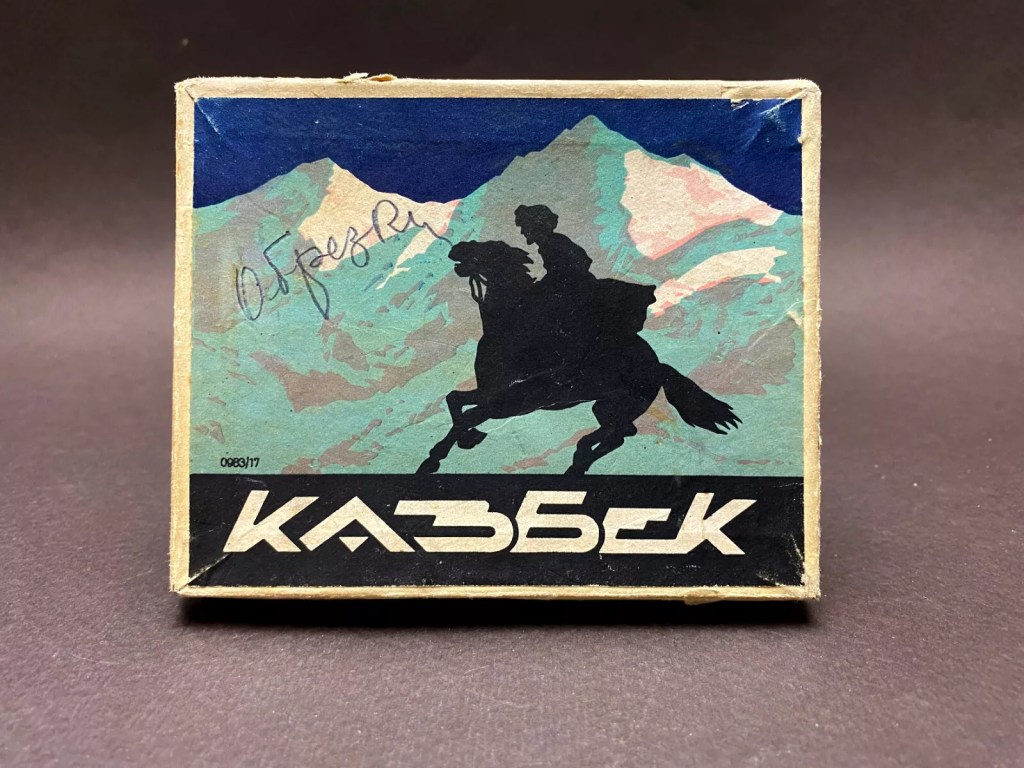

Kazbek:

Lt. General Vozdvishensky of RUMID smokes a Kazbek cigarette. All I’ve really found on Kazbek is that the cigarettes were relatively expensive and so were considered a sign of wealth or luxury.

Molotov:

Vozdvishenky “remembered how Molotov had privately told him, when Beria was dead, that General G would go far.” Vyacheslav Molotov (1890 – 1986) was head of the Soviet government from 1930 – 1941, and Minister of Foreign Affairs from 1939 – 1949 and 1953 – 1956. He was a close ally of Stalin for years. He took part in a failed coup against Khrushchev in 1957, after From Russia with Love was written. During the 1939 – 1940 Winter War between Russia and Finland, Molotov claimed the Soviets were delivering food when they were really dropping cluster bombs. Finns referred to the bombs as Molotov bread baskets, and their own homemade explosives as Molotov cocktails.

MGB Predecessors:

Fleming lists some of “the famous predecessors of the MGB – the Cheka, the Ogpu [OGPU], the NKVD and the MVD…” Like corporations seeking to confuse the public about past deeds, Soviet government agencies went through frequent name changes and redistribution of duties. According to Wikipedia, the chronology of the USSR’s primary state security ministry was: Cheka (1917 – 1922), GPU (1922 – 1923), OGPU (1923 – 1934), NKVD (1934 – 1941), GUGB of the NKVD (1941 – 1943), NKGB (1941, 1943 – 1946), MGB (1946 – 1953), MVD (1953 – 1954), and KGB (1954 – 1991).

Metteur en scène:

Serov is described as “metteur en scène of most of the great Moscow show trials…” Metteur en scène loosely translates from French as director, meaning that Serov was pulling the strings either formally or informally.

Central Caucasus:

Serov is also linked to “the bloody genocide in the central Caucasus in February 1944…” Conflict with Chechens in the Caucasus goes back to Chechen resistance to Russian expansion in the 1700s and 1800s. The Soviets conducted mass deportations of people of multiple ethnicities from the Caucasus in the 1940s. Hundreds of thousands were sent to Central Asia and Siberia and about one out of four are believed to have died. However, here Fleming specifically refers to Operation Lentil. In 1936, Stalin forced autonomous Chechen and Ingush territories together into the Chechen-Ingush Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic. After more conflict, fearing that the presence of millions of Muslims in the USSR might inspire rebellion throughout Central Asia, and in search of forced labor, Beria ordered the entire Chechen-Ingush ASSR population to be deported. Operation Lentil began on February 23, 1944, and nearly half a million people were forcibly moved. A quarter or more of those are estimated to have died during transport or in labor camps, and many were shot because they were too old or otherwise unable to survive the journey.

Baltic States:

Serov had also “inspired the mass deportations from the Baltic states…” Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania constitute the Baltic states. The Soviets occupied the region in 1940 and conducted staged elections which resulted in all three countries “voluntarily” joining the USSR. As a result, from 1940 – 1953, the Soviets deported over 200,000 people (about 10% of the adult population) to labor camps or other areas. The deportations were paused when Germany invaded the region in 1941, but it turned out the Nazis were just as cruel as the USSR, killing over 250,000 Jews in Latvia and Lithuania.

German Scientists:

Serov is also credited with “the kidnapping of the German atom and other scientists who had given Russia her great technical leap forward after the war.” At the end of World War II, the U.S., USSR, Britain, and France all claimed repatriations from Germany, and that included people of important technical skills, such as nuclear physicists and engineers from missile and rocket programs. We established in Moonraker that a few of these scientists and engineers went to Britain. Many went to the U.S. But the USSR conducted the most brazen transfer. In the immediate aftermath of the war, the Soviets tried to simply take over technical facilities in the region of Germany they controlled. That left them exposed very close to Western territory, and the 1945 Potsdam Conference prohibited weapons development in Germany. So on October 21-22, 1946, the Soviets undertook Operation Osoaviakhim to transport without notice approximately 6,500 scientists, engineers, technicians, and some of their families, along with entire research facilities, into the USSR. They included people and materials related to photographic R&D, liquid- and solid-fuel rocket engines, telemetry, petroleum, and other disciplines.

Litvinov:

Vozdvishensky seems the most capable among the assembled group of standing up to G, partly because of his extensive international service, including time “as a ‘doorman’ at the Soviet embassy in London under Litvinoff.” Maxim Litvinov (1876 – 1951) served as the Soviet Union’s unofficial ambassador to Britain in 1917 – 1918. He was also the People’s Commissar for Foreign Affairs (roughly equivalent to the U.S. Secretary of State) from 1930 – 1939. That’s most likely when Vozdvishensky would have served under Litvinov. Litvinov also served as ambassador to the U.S. from 1941 – 1943.

TASS:

Vozdvishensky was also stationed in New York City with TASS, the Soviet (and now Russian) state-owned news agency. The agency was established in 1902 but not known as TASS until 1925, and during the Soviet period it was the central news agency for newspapers, radio, and TV. The NKVD and KGB commonly placed agents as TASS employees as a cover for international espionage. TASS still operates today and made numerous false claims during Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine.

Amtorg:

Vozdvishensky also served in London with Amtorg. The Amtorg Trading Corporation was the USSR’s trade representative in the U.S., established in 1924 with its primary office in New York City. Amtorg negotiated contracts with U.S. companies and handled the majority of exports from the Soviet Union. Amtorg also dealt with delivery of Lend-Lease supplies to the USSR during World War II. Despite frequent accusations that Amtorg was an espionage front, it seems that most espionage activity was conducted by the Soviet embassy in Washington, DC, established in 1933.

Kollontai:

Vozdvishensky was also a military attaché at the Soviet embassy in Stockholm “under the brilliant Madame Kollontai.” Alexandra Kollontai (1872 – 1952), after a period of exile, joined the Bolsheviks in 1915 and was a voting member of the Central Committee that chose to implement the October Revolution in 1917. She defended women’s rights as a Marxist feminist. Kollontai was a Soviet diplomat stationed in Mexico, Norway, and Sweden, and was the Ambassador to Sweden from 1943 – 1945. Apparently Kollontai stepped back from her feminist views over the years, which may explain why someone like Vozdvishensky would consider her brilliant.

Sorge:

Vozdvishensky “had helped train Sorge, the Soviet master spy, before Sorge went to Tokyo.” Richard Sorge (1895 – 1944) was a Soviet intelligence officer who worked undercover as a journalist in China, Germany, and Japan. While Sorge was born in what is now Azerbaijan, his father was German, so Sorge grew up in Germany and served in the German army during World War I. While in Japan, Sorge’s German ancestry made him welcome at the German Embassy, allowing him to conduct surveillance on both Japan and Germany. Sorge was able to alert his government about Germany’s planned invasions of Poland in 1939 and the Soviet Union in 1941. He was also able to provide assurance that Japan had no plans to invade the USSR. The Japanese arrested Sorge for espionage in 1941 and he was hanged in 1944.

Lucy:

During a stint in Switzerland, Vozdvishensky “had helped sow the seeds of the sensationally successful but tragically misused ‘Lucy’ network.” The Lucy spy ring in Switzerland was overseen by Rudolf Roessler (1897 – 1958), a Bavarian who left for Switzerland when Hitler came to power. Roessler facilitated the transfer of classified information from German officers who opposed Hitler to the Swiss, British, and USSR. Like Sorge, Roessler alerted the Soviets to Germany’s planned invasion in 1941. The GRU officer who received Roessler’s information was Alexander Radó (1899 – 1981), who only knew that his source was based in Lucerne, so created the code name “Lucy.” I’m intrigued by what Fleming might have known about Lucy, as the full story didn’t become public until 1966, and some of Roessler’s sources are unknown to this day.

Rote Kapelle:

Continuing Vozdvishensky’s lengthy international experience, he was a part-time courier to the “Rote Kapelle.” The Red Orchestra, or Rote Kapelle, was an informal network of German opponents to Hitler and the Nazis. They circulated propaganda, helped Jews escape Germany, and provided intelligence to allied governments. The name was applied by the Abwehr, the German intelligence agency. The term Red Network was loosely applied to groups and individuals working independent of each other. About 400 individuals are known to have been a part of it.

Burgess and Maclean:

Finally, Vozdvishensky was “on the inside of the Burgess and Maclean operation…” Guy Burgess (1911 – 1963) and Donald Maclean (1913 – 1983) were part of the Cambridge Five spy ring that operated in the UK after being recruited by the NKVD while they were students at the University of Cambridge. (One of the five claimed they were not recruited until after graduation.) All five worked in the British government and provided so much intelligence to the USSR that the Soviets began to doubt the reliability of the information. Once the U.S. and British became aware of moles within the British government, two of the five, Burgess and Maclean, defected to the Soviet Union in 1951. MI5 and MI6 attempted to keep the fiasco confidential, but once it became public it did a lot to discredit British intelligence and damage relations between the U.S. and British intelligence establishments. Numerous novels and movies have taken inspiration from the Cambridge Five and subsequent cover-up, including Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy and A Perfect Spy by John le Carré, The Fourth Protocal by Frederick Forsyth, The Jigsaw Man (1983), and A Different Loyalty (2004). Burgess became bitter in the Soviet Union as he had intended to return to Britain. Maclean integrated more successfully and did some teaching and writing, and he outlived Burgess by nearly twenty years.

Mathis:

In choosing a target for their konspiratsia, the Soviet officers consider our friend René Mathis, now head of the French Duexième, whose help was so important to Bond in Casino Royale. Vozdvishensky identifies Mathis as a Mendès France appointment. Pierre Mendès France (1907 – 1982) was the French prime minister for a brief period from 1954 – 1955, presumably the time when he would have appointed Mathis. Mendès France played a significant role in ending French military involvement in Indochina in 1954.

England is Important!:

Fleming allows the Soviet officers to praise England, which seems improbable, particularly given their knowledge of the Cambridge Five, among other things. (In fairness, Fleming probably didn’t know there were five, but he clearly knew of Burgess and Maclean by the time he wrote the novel.) England’s “Security Service is excellent,” Vozdvishensky says. Then, “MI5 employs men with good education and good brains. Their Secret Service is still better.” He praises Britain’s agents for their hard work despite receiving low pay and no special privileges, in contrast to Red Grant’s significant salary and his material luxuries alluded to in Chapter 1. It seems like a bit of wishful thinking regarding Britain’s role in world politics. Nobody does it better!

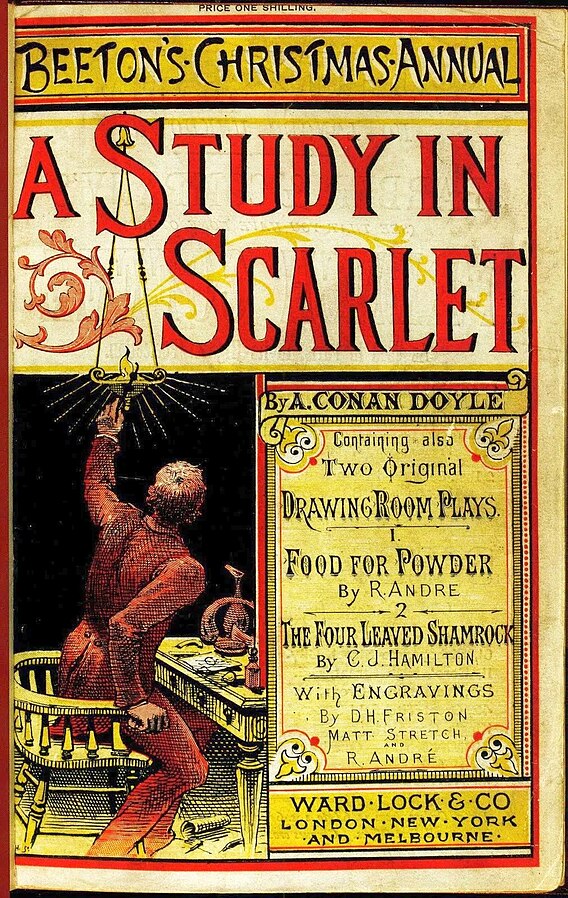

Scotland Yard and Sherlock Holmes:

Vozdvishensky qualifies his praise of England, which again sounds like Fleming’s own opinions, that maybe his post-war country is regarded more for the memory of past deeds than present or future status. “Of course, most of their strength lies in the myth – in the myth of Scotland Yard, of Sherlock Holmes, of the Secret Service.” Scotland Yard is the headquarters for London’s Metropolitan Police, given its name from the street (Great Scotland Yard) on which the original headquarters was located. Sherlock Holmes, of course, was the fictional detective created by Arthur Conan Doyle (1859 – 1930) beginning with A Study in Scarlet in 1887. It’s odd that Fleming chooses two real agencies and one fictional character. This may also be an opportunity for Fleming to poke fun at himself, as by this time his own novels were part of the “myth” of the British Secret Service.

Dumb Americans:

The group is quick to dismiss the U.S. intelligence community as a worthy target. “Americans try to do everything with money,” Vozdvishensky says. And, “Personally I do not think the Americans need engage the attention of this conference.”

M:

Returning to the subject of England, the Soviets have some knowledge of M but conclude that he would not only be a difficult target but would not generate the desired scandal. “He does not drink very much. He is too old for women.”

6 Death Warrant

Y*b*nna mat:

G shares the phrase “Y*b*nna mat!” when Bond’s name is brought up. It’s clearly profanity in the Russian language, but I’m unable to determine the specific meaning.

Dynamos:

Vozdvishensky (again, the only one who seems willing to stand up to G) says, “I am interested in football [soccer], but I cannot remember the names of every foreigner who has scored a goal against the Dynamos.” The Dynamo Sports Club was established in 1923 to conduct sports and fitness activities throughout the USSR. Under that was FC Dynamo Moscow, the soccer club originally named Club Sokolniki Moscow but renamed to Dynamo after being taken over by the Cheka (forerunner of the MGB and KGB) in the wake of the Revolution. The Dynamos were the first Soviet soccer club to tour the West when they completed an undefeated tour of the UK in 1945. During the Cold War the club was sometimes referred to as “the cops” because of their ties to the MVD and, later, the KGB. Beria was one of the club’s important supporters. The Dynamos still compete in Russia today.

Past Adventures:

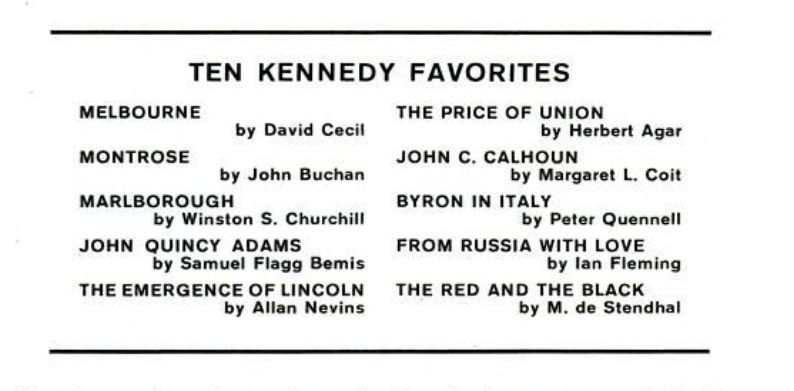

G and Nikitin demonstrate an impressive level of knowledge of Bond’s past exploits, referring to Le Chiffre (Casino Royale), Mr. Big (Live and Let Die), and Drax (Moonraker). Only Diamonds Are Forever (so far) exists somewhat independently of Cold War politics.

Unhappy Family:

The infighting between these senior Soviet officers, reflecting both personal ambitions and inter-agency control struggles, is quite enlightening. For example, Slavin and Nikitin dispute where to place responsibility for the Moonraker rocket failure. While similar maneuvering may very well be going on within the British government, and certainly between Britain and other Western allies, we readers have seen a fairly unified front – as symbolized by the cooperation between Bond and Felix Leiter or René Mathis, and by Bond’s unquestioning loyalty to M. This is probably not deliberate foreshadowing on the author’s part, but it certainly helps explain who will be victorious in the end.

Same Time Last Year:

Trying to place an exact chronology on the timing of the Bond novels is perhaps a futile exercise, and unnecessary because we’re primarily here for entertainment. But speculation can also be fun, and here the conference of officers describes “the rocket affair” as taking place three years ago and the “diamond smuggling affair” was last year. Moonraker would appear to take place in 1954, though Bond experts place it in 1953. That would put Diamonds Are Forever in 1955 and From Russia with Love in 1956, not far from my estimate in Chapter 2.

Heroes:

Vozdvishensky again seems to speak to Fleming’s personal concerns about Britain’s status in the world and the direction of British society and culture: “The English are not interested in heroes unless they are footballers or cricketers or jockeys.” Soon after, he adds, “In England, neither open war or secret war is a heroic matter. They do not like to think about war, and after a war the names of their war heroes are forgotten as quickly as possible.” Is Fleming suggesting that Britain is already losing sight of the lessons of World War II, and of the dangers of expansionist policies in unfriendly nations?

Lone Wolf:

Nikitin says about Bond, “He is said to be a lone wolf, but a good looking one.” We readers may be inclined to agree, but is Bond really a lone wolf? He thinks often of how to interpret M’s instructions and how much leeway he has in carrying out his orders. He might stretch the envelope occasionally, but from a professional standpoint I’m not sure “lone wolf” is really an accurate description of Bond.

Bond vs. Grant:

We again have an opportunity to compare and contrast Red Grant with James Bond (who has yet to appear in his own book!). Bond and Grant seem to be somewhat closely matched in terms of physical prowess and combat skills. Both are drawn to tokens of luxury – Grant carries a Fabergé cigarette case and Bond smokes custom cigarettes with “three gold bands.” Both are loyal to their respective causes for different reasons. Bond however, is identified with the vices of drink and women, giving Bond more of an appreciation of life than Grant but also, potentially, providing the very weaknesses that could lead to Bond’s demise.

Highsmith:

We’re told that Bond joined the Secret Service in 1938 “and now (see Highsmith file of December 1950) holds the secret number ‘007’ in that Service.” Who is Highsmith? Some have speculated that Highsmith might be the name of the second person Bond killed to obtain his 00 status, but Casino Royale identifies his targets as Japanese and Norweigan, neither of which sounds like a potential “Highsmith.” Perhaps Highsmith is a code name. While unlikely, I like to think of it as a veiled reference to Patricia Highsmith (1921 – 1995), whose first novel, Strangers On a Train, was published in 1950 and adapted for the screen by Alfred Hitchcock in 1951. The Talented Mr. Ripley was published in 1955, only one year before Fleming wrote From Russia with Love.

CMG:

The Soviet file on Bond claims he received a CMG in 1953. Companion of the Most Distinguished Order of St. Michael and St. George (CMG) does not come with a Sir or Dame honorific. The appointment (it is not technically an award) was introduced by George, Prince of Wales (1762 – 1830), later to become King George IV, and is based on important non-military service to the UK. Bond’s CMG was disclosed in Moonraker, though we have no details on how he earned it.

Colonel Klebb:

We are introduced to Rosa Klebb, head of SMERSH Otdyel II, who will be responsible for implementing the scheme to assassinate Bond. At this stage we only learn two things about Klebb, but they are perhaps all we need to know. One is that she wears the Order of Lenin, created by the Soviet Central Committee in 1930 for outstanding service and awarded to both individuals and organizations. The first Order of Lenin was presented to Komsomolskaya Pravda, a daily newspaper aimed at readers aged 14 to 28. At the time of From Russia with Love, the order also acknowledged 25 years of “conspicuous” military service, which gives us a clue to Klebb’s dedication and longevity. Second, Klebb is as inhuman as Bond’s other villains; in Klebb’s case, she is “toad-like.”

It’s widely believed that Rosa Klebb is loosely based on Zoya Voskresenskaya (1907 – 1992), who was a real NKVD officer. One of Voskresenskaya’s functions was coordination of the Rote Kapelle mentioned in Chapter 5. Fleming had written an article about Voskresenskaya while reporting for The Sunday Times. She fell out of favor with the Soviet government when she spoke out against an NKVD housecleaning conducted after Stalin’s death. Once retired from government service, she became a highly successful author of children’s books.

7 The Wizard of Ice

Chess Clocks:

The chapter opens with a chess clock, a reminder that our two opponents – both individuals and societies – are on different schedules but still approaching a common destiny. Chess players will be familiar with the pressures of a timed match; Fleming must have understood, as he describes the device as a “huge sea monster.” A chess clock is really two clocks in one unit, each typically set to the same amount of time. As each player is eligible to move, their respective clock ticks down while their opponent’s clock is stopped. A player loses if their clock runs out of time before a checkmate occurs. The clocks can also be set for different amounts of time, as a way of handicapping one player who is considered to have the advantage over another.

Kronsteen:

We meet Kronsteen – I don’t believe we ever learn his full name – champion chess player and the “wizard if ice” referred to in the chapter title. We later learn that he is an honorary colonel in the SMERSH planning department, meaning that he reports to Colonel Klebb.

Makharov:

Kronsteen’s opponent, Makharov, appears briefly but we will not see him after he loses this match. Shortly we learn that Makharov is from Georgia, the eastern European nation that at the time was one of the Soviet Republics. Makharov (or Makarov) seems to be a faily common name in the region; as far as I can tell this does not refer to any historic figure.

Grand Master:

Kronsteen believes that he will be eligible for “Grand Mastership” after defeating Makharov. Because of the timing of the novel, this may have one of two meanings. In 1950, the International Chess Federation (FIDE) created the title Grandmaster and initially awarded it based on committee decisions. Starting in 1953, the title was assigned based on more formal criteria. Prior to 1950, Soviet chess players did not compete outside the USSR, and the Soviet Chess Federation awarded the title Grandmaster of the USSR to select players. Since Kronsteen is competing inside the Soviet Union against another Soviet player, I suspect the pre-1950 title is what Fleming refers to.

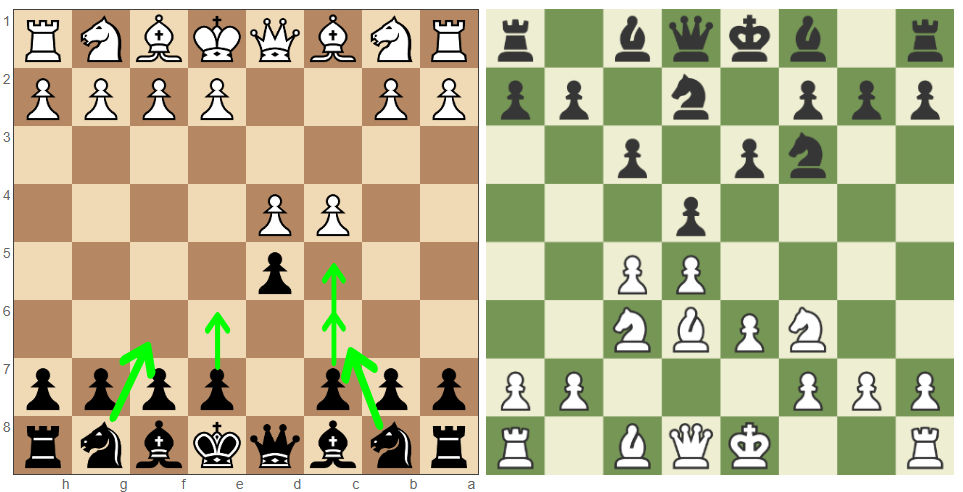

Queen’s Gambit Declined:

In the game against Makharov, Kronsteen “had introduced a brilliant twist into the Meran Variation of the Queen’s Gambit Declined.” This gets into details of chess that are largely over my head, but the Queen’s Gambit involves white (always first to move in chess) offering the sacrifice of the queen bishop’s pawn early in the match. The Queen’s Gambit Declined simply means that black makes another move rather than taking the offered pawn. A common response to the Queen’s Gambit is the Semi-Slav Defense, where black advances its pieces to attack the white queen’s pawn in the center of the board. The Meran Variation of the Semi-Slav Defense involves black temporarily sacrificing control of the center to develop the game in another direction. My own chess-playing is too simplistic to fully understand the implications of some of these maneuvers.

Pushkin Ulitza:

The official car picks up Kronsteen on Pushkin Ulitza. (I’m uncertain why “Ulitsa” is spelled differently here in my edition.) As far as I can tell, there is no street named Pushkin in Moscow. There is, however, Pushkin Square, a busy public space in central Moscow. Originally Strastnaya Square, the space was renamed in 1937 in honor of Russian writer Alexander Pushkin (1799 – 1837). I’m guessing this is where Kronsteen is collected.

ZIK?:

Kronsteen is picked up in “the usual anonymous black ZIK saloon.” This is almost certainly a misspelling of ZIS as described in Chapter 2.

Stolzenberg:

In their meeting with G, Klebb speaks of a previous case in which the life and reputation of a spy was destroyed, saying, “The spy was also a pervert.” I can find no information on an actual such case, though the term “pervert” was loosely applied on both sides of the Iron Curtain.

Chess Pieces:

We get some fascinating insight into Kronsteen’s personality. “To him all people were chess pieces. He was only interested in their reactions to the movements of other pieces.” He also thinks all people can be reduced to simple motives and labels, their behavior as rigid as the moves of chess pieces, thinking, “Their basic instincts were immutable. Self-preservation, sex and the instinct of the herd – in that order.” The fact that Kronsteen doesn’t fully understand the true motives of some chess pieces – Bond, as we know, will place service above self-preservation – and his inability to consider the adaptability of human behavior, are perhaps the primary reasons the SMERSH plan will ultimately fail. Still, the chess piece analogy is an interesting perspective on the entire story, with the British Prime Minister (Anthony Eden) and the Soviet Premier (Nikita Khrushchev) as the “kings” maneuvering higher level pieces like M and G, who in turn manipulate pawns like Bond and Grant. Or perhaps in this analogy Elizabeth II (1926 – 2022), Queen of England at the time, was the senior British chess piece?

Pavlov:

Kronsteen considers one’s parents an important determinant of behavior, “whatever Pavlov and the Behavourists might say…” Ivan Pavlov (1849 – 1936) was a Russian physiologist who was awarded a Nobel Prize in 1904 for his research in digestion, and you do not want to know what kind of torture he inflicted on people and animals in order to achieve that. It was during this research, however, that Pavlov observed dogs salivating prior to receiving food, leading to an understanding of conditioned reflexes and behavior therapy.

Spanish Civil War:

Klebb’s rise in the Soviet defense establishment began with the Spanish Civil War as a double agent within POUM, the Worker’s Party of Marxist Unification, formed in Spain in 1935 as a communist party in opposition to Stalinism. Klebb was with OGPU, the Soviet intelligence service that was succeeded by the NKVD. As for the Spanish Civil War, it was fought in 1936 to 1939 between Nationalists, monarchists, and others led primarily by General Francisco Franco (1892 – 1975), and Republicans, a coalition of socialists, separatists, and others. Estimates put the war’s combined death toll of cilivians and combatants at over 400,000. The violent and ideological nature of the war led some to see it as a prelude to World War II.

Andreu Nin:

While in Spain, Klebb was a right hand, and perhaps mistress, of Andreas (Andreu) Nin (1892 – 1937). Nin was a prominent translator of works from Russian to Catalan, including Anna Karenina, Crime and Punishment, and others. He was also a political activist who became leader of POUM (see above) in 1936. In 1937, Nin was captured by the NKVD, perhaps tortured, and executed. (In the context of the novel it is speculated that Klebb herself may have executed Nin.)

Neuter Phlegmatic:

Kronsteen puts Klebb in a similar category as Grant, and Bond, a lone wolf. He describes her as “neuter” vs. Grant’s asexuality. The two terms are often used interchangeably, but here Kronsteen seems to see Klebb as open to sexual acts with any partners of any gender, whereas Grant clearly has no interest in sex whatsoever. (Either way, they are both distinct from Bond, which is the primary point of these characterizations.) Klebb is also considered “phlegmatic.” Kronsteen has a fairly archaic belief system going back to Hippocrates (460 – 370 BC) that all people can be described with some combination of four categories: melancholic, phlegmatic, sanguine, choleric. A phlegmatic, per Kronsteen, would be “imperturbable, tolerant of pain, sluggish.”

Tricoteuses:

Kronsteen compares Klebb to the tricoteuses of the French Revolution, who “sat and knitted and chatted while the guillotine clanged down…” Tricoter is the French verb “to knit.” Working class market-women in Paris were active participants in the French Revolution, including conducting the Women’s March on Versailles in 1789 in protest of shortages and high prices of bread. When the Reign of Terror – the public execution of thousands who opposed the Revolution – began, the women brought their knitting to the Place de la Révolution, known today as Place de la Concorde, and patiently watched. In fact, we will see Klebb knitting in the book’s final scene.

Orange Hair:

Klebb has orange hair, just another shade of red, like Grant. She is further dehumanized with such descriptions as “squat,” “dumpy,” “a badly packed sandbag,” a “wet trap of a mouth,” “big peasant’s ears,” and so on.

Knobkerries:

Kronsteen compares Klebb’s fists with knobkerries. A knobkerrie (or knobkerry) is a wooden club used primarily in Southern and Eastern Africa. They have a large knob on the receiving end to better damage one’s victim. It was used as both a club and a thrown weapon like a spear, but could also be used as a walking stick.

Fouché:

Kronsteen cites “a Frenchman, in some respects a predecessor of yours, Fouché, who observed that it is no good killing a man unless you also destroy his reputation.” Joseph Fouché (1759 – 1820) was a participant in the French Revolution and was, among other things, the French Minister of Police. Fouché was known by some as the Executioner of Lyon because he was sent to Lyon in 1793 to execute nearly 2,000 who had opposed the Revolution.

Bulgarian Assassins:

Kronsteen claims that “any paid Bulgarian assassin” could handle the job if a straightforward execution was the goal. Bulgarians were blamed for the attempted bombing in Casino Royale. Bulgaria was a member state of the USSR from 1946 to 1991, but I’m still not sure why Bulgarians in particular are linked with assassinations.

Eccentricity:

Kronsteen advises Klebb, “The English pride themselves on their eccentricity. They treat the eccentric proposition as a challenge.” The English certainly have a reputation as eccentrics, but whether that is a stereotype or an accurate cultural trait is a gray area. Books like English Eccentrics and Eccentricities by John Timbs and The English Eccentrics by Edith Sitwell both reflect and contribute to the image. Historic exmples are easy to find. John Bentinck (1800 – 1879), 5th Duke of Portland, was so reclusive that he banned visitors from his estate and built an estimated 15 miles of tunnels underground to avoid going outside. English philosopher John Stuart Mill (1806 – 1873) wrote, “That so few now dare to be eccentric, marks the chief danger of the time… They are the visionaries who make great imaginative leaps.” This same atittude can be contrived for effect, however, as when famous rich guy Richard Branson said, “anything, however outlandish, that generates media coverage, reinforces my image as a risk-taker who challenges the establishment.” A lot of this “eccentric” behavior seems more a result of obscene wealth and privilege rather than culture. Despite Kronsteen’s goal of an eccentric plan, I don’t believe it’s the eccentricity of the scheme that ultimately draws in M or Bond. Based on their own conversation later in the book, the real hook is the opportunity to use Bond as bait to draw out the Soviets and defeat them at their own game.

8 The Beautiful Lure

Tatiana Romanova:

Despite Bond’s strong presence in the previous two chapters, he still hasn’t made a physical appearance in the book. Now, however, we do meet the woman who will tempt him, Tatiana Romanova, a Corporal of State Security.

Boris Goudonov:

Tatiana listens to a radio broadcast of Borid Godunov (Goudonov) performed by the Moscow State Orchestra. The opera was composed by Modest Mussorgsky (1839 – 1881) and was based on Alexander Pushkin’s play of the same name written in 1825. The opera was first performed in Saint Petersburg in 1873. The story dramatizes the reign of Tsar Boris Godunov (1552 – 1605) and his successors Feodor II (1589 – 1605) and False Dmitry I (1582 – 1606). The Moscow State Symphony Orchestra was established in 1943 and often performs in the Moscow Conservatory, opened in 1866.

Sadovaya – Chernogryazskaya Ulitsa:

Fleming spells it a bit differently, but Tatiana lives in a 1939 apartment building, “the women’s barracks of the State Security Department,” on Sadovaya-Chernogryazskaya Ulitsa. The street is on the northeastern section of the Garden Ring (see Chapter 4) around central Moscow. No specific address is given so I’m unable to determine if the building Fleming describes actually existed, or if it still stands.

1200 Rubles:

Tatiana reflects on the relative privileges of her life in Moscow, where she receives a salary of 1200 rubles / month. That’s considerably less than Red Grant (Chapter 3) but still apparently a good income for 1950s Moscow.

Greta Garbo:

This is a Bond novel, so of course Tatiana does us the favor of scrutinizing her appearance in great detail. If she is to seduce Bond, she must be his equal, and if Bond resembles Hoagy Carmichael (as described in Casino Royale and Moonraker), then Tatiana must resemble Swedish actress Greta Garbo (1905 – 1990). Garbo began acting in silent films in1924 and made her first talkie in 1930. Her 1941 film Two-Faced Woman was a bit of a critical flop and she never appeared in another movie. By the time From Russia with Love was published, Garbo had become a naturalized U.S. citizen and lived in New York City.

Hotel Moskva:

Tatiana recalls in vague terms an evening at Hotel Moskwa, or Hotel Moskva. The hotel was constructed between 1932 and 1938, and opened while still under construction in 1935. The hotel included an entrance to a Moscow Metro station. An illustration of Hotel Moskva can be found on some Stolichnaya vodka labels. The original building was demolished in 2004 and replaced with a visually similar building that is now home to a Four Seasons Hotel.

Turkmenistan:

Tatiana’s elitism comes through when the radio broadcasts “the whimpering discords of an orchestra from Turkmenistan.” Turkmenistan is a central Asian country bordered by Afghanistan, Iran, and other countries. Turkmen territory was seized by the Russian Empire in 1881 and became the Turkmen Soviet Socialist Republic in 1924. The Turkmen Republic declared itself independent in 1990. The region is home to significant natural gas reserves and is considered highly corrupt and an extreme violator of human rights. Tatiana finds the Turkmenistan orchestra not “kulturny,” or cultured, but instead something from “barbaric outlying states.”

Denekin:

We never meet him in person, but Tatiana receives a call from Professor Denekin with orders to go to Klebb’s apartment. He clearly has some influence on Tatiana, as earlier in the chapter she recalled “a word of praise” she had received from him that afternoon.

Queen of Spades:

Debating calling Denekin back for more information, Tatiana imagines the professor’s feeling after hanging up the phone: “You had got the dreadful card out of your hand. You had passed the Queen of Spades to someone else.” The significance of the Queen of Spades seems to vary considerably by game or use and also by who is making the interpretation. Fleming may be referring to Alexander Pushkin’s story The Queen of Spades, published in 1834. The story involves a German officer who causes the death of an elderly woman who he believes knows a secret about three lucky cards for gambling. The woman appears in a dream and tells the officer to gamble at faro, a French card game, on the three, the seven, and the ace. The officer does this with success, until he accidentally wagers instead on the Queen of Spades and loses all his money, later becoming insane and ending up in an asylum. Russian composer Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840 – 1893) was inspired by Pushkin’s story to write the 1890 opera The Queen of Spades. Between Pushkin and Tchaikovsky, that seems kulturny enough that Tatiana would be aware of the story.

9 A Labour of Love

Scents: