Creativity is, by its nature, fitful and inconstant, easily upset by constraint, foreboding, insecurity, external pressure. Any great preoccupation with the problems of ensuring animal survival exhausts the energies and disturbs the receptivity of the sensitive mind.

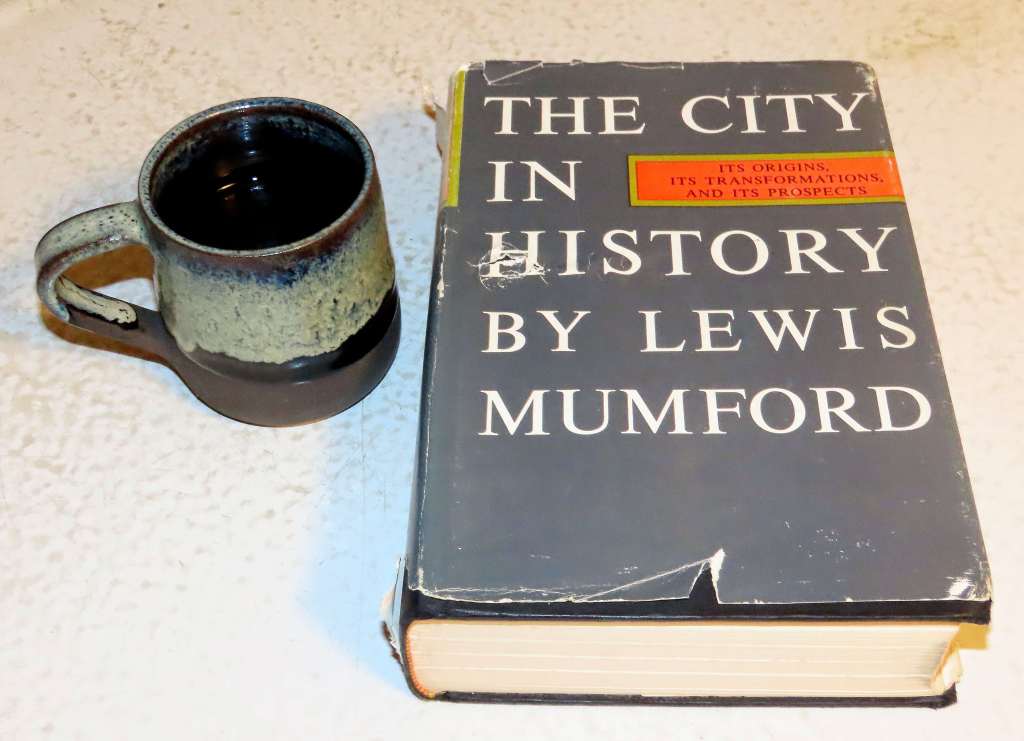

Lewis Mumford, The City in History, p. 99

Soon after returning home from a wonderful vacation in Ecuador, my wife fell ill to a cold or flu, and I followed soon after. While I recovered I watched episodes of the original Hawaii Five-O series that aired on CBS from 1968 to 1980. I never watched Five-O when it originally aired but it’s a far more interesting show than I expected. Jack Lord makes for a compelling lead, the writing is generally well done if a bit melodramatic at times, exteriors were filmed almost entirely on location in Hawaii, and of course the show has one of the great TV theme songs, composed by Morton Stevens. The one negative with Hawaii Five-O is the extent to which supporting characters are diminished to make room for Jack Lord’s character. While no criminal mastermind can resist the smoldering eyes of Steve McGarrett, James MacArthur, Kam Fong, and Zulu all deserved better. Seriously, if you have an actor named Zulu in your cast, he should get plenty of screen time. Still, it’s an entertaining series that holds up quite well.

One of the highlights of our Ecuador vacation, believe it or not, was our chance discovery of the English Bookshop in Quito, operated by a very friendly British chap named Mark. Mark treated us to a hot cup of Yorkshire Gold tea and told us a little of his history in Ecuador. And I came across a somewhat rare used copy of Lewis Mumford’s 1961 book The City in History. It’s a fascinating book, dense with information and insights, that I’ve only begun to make my way through. Mumford is so quotable, it’s hard to know where to begin:

- P. 12: “Let me emphasize neolithic man’s concentration on organic life and growth: not merely a sampling and testing of what nature had provided, but a discriminating selection and propagation, to such good purpose that historic man has not added a plant or animal of major importance to those domesticated or cultivated by neolithic communities.”

- P. 15: “What we call morality began in the mores, the life-conserving customs, of the village. When these primary bonds dissolve, when the intimate visible community ceases to be a watchful, identifiable, deeply concerned group, then the ‘We’ becomes a buzzing swarm of ‘I’s’, and secondary ties and allegiances become too feeble to halt the disintegration of the urban community.”

- P. 24: “Both vocations [organizer and conqueror] call forth leadership and responsibility above, and demand docile compliance below. But that of the hunter elevated the will-to-power and eventually transferred his skill in slaughtering game to the more highly organized vocation of regimenting and slaughtering other men; while that of the shepherd moved toward the curbing of force and violence and the institution of some measure of justice, through which even the weakest member of the flock might be protected and nurtured. Certainly coercion and persuasion, aggression and protection, war and law, power and love, were alike solidified in the stones of the earliest urban communities, when they finally take form. When kingship appeared, the war lord and the law lord became land lord too.”

- P. 33: “As far as the present record stands, grain cultivation, the plow, the potter’s wheel, the sailboat, the draw loom, copper metallurgy, abstract mathematics, exact astronomical observation, the calendar, writing and other modes of intelligible discourse in permanent form, all came into existence at roughly the same time, around 3000 B.C. give or take a few centuries. … This constituted a singular technological expansion of human power whose only parallel is the change that has taken place in our own time. In both cases men, suddenly exalted, behaved like gods: but with little sense of their latent human limitations and infirmities, or or the neurotic and criminal natures often freely projected upon their own deities.”

- P. 40: “The more complex and interdependent the process of urban association, the greater the material well-being, but the greater the expectation of material well-being, the less reconciled would people be to its interruption, and the more widespread the anxiety over its possible withdrawal.”

- P. 102: “If we could recapture the mentality of early peoples, we should probably find that they were, to themselves, simply men who fished or chipped flint or dug as the moment or the place might demand. That they should hunt every day or dig every day, confined to a single spot, performing a single job or a single part of a job, could hardly have occurred to them as an imaginable or tolerable mode of life. Even in our times primitive peoples so despise this form of work that their European exploiters have been forced to use every kind of legal chicane to secure their services.”

- P. 107: “Private property begins…with the treatment of all common property as the private possession of the king, whose life and welfare were identified with that of the community. Property was an extension and enlargement of his own personality, as the unique representative of the collective whole. But once this claim was accepted, property could for the first time be alienated, that is, removed from the community by the individual gift of the king.”

Leave a reply to Friday Food for Thought: 21 July 2023 – The Creative Life Adventure Cancel reply