Welcome back to the Creative Life Adventure.

(See my previous essays Our Brother’s Keeper and Deliver Us From Evil for overviews of the first four seasons of Miami Vice.)

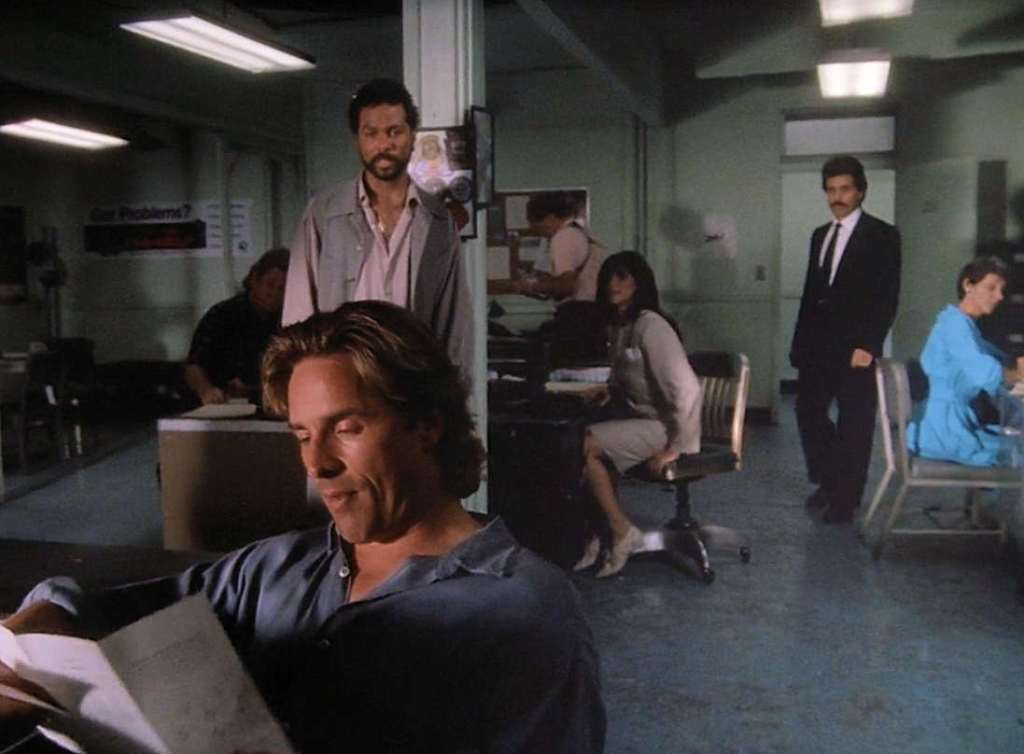

After two generally excellent seasons, followed by two seasons of mixed results, the fifth and final season of Miami Vice, airing during the 1988-1989 season, gave us little to be excited about. Knowing the series was at an end, all of the primary cast, even the two leads, Philip Michael Thomas and Don Johnson, made sporadic appearances. Frequently throughout the season, either Ricardo Tubbs (Thomas) or Sonny Crockett (Johnson) would appear in the beginning of an episode with some excuse – testifying at a trial, visiting family, etc – that would explain their absence for the rest of the episode.

Everyone, it seems, had given up. Dick Wolf left after serving as a producer for Season 3 and an executive producer for Season 4. Composer Jan Hammer also departed, replaced by Tim Truman and a very different acoustic experience for a series known for its unique musical style. Like cinematic Batman, the show became consistently darker over time. So it should be no surprise that Crockett and Tubbs, hardly naive but still hopeful when they became partners in the pilot episode, become increasingly hopeless and cynical.

The stress is so great that Crockett seems to have forgotten that he was married recently and his wife was murdered. For example, in “To Have and to Hold” (S5E10), Crockett and Tubbs both experiment with a kind of domesticity and the temptations of civilian life – Tubbs by getting involved with the widow of a drug lord, and Crockett by reconnecting with his son and first wife, now remarried and pregnant – with no mention whatsoever of the late Caitlin Davies. At least the Sonny Burnett storyline set up at the end of Season 4 is resolved in a reasonable fashion, with consequences. In “Bad Timing” (S5E4), Crockett gives testimony while dressed in white under bright lights, implying judgment before heaven because Crockett believes he has killed a perpetrator by drowning. Before the Crockett/Tubbs partnership, so crucial to the series, can be restored, Crockett is confronted multiple times over his attempts to kill Tubbs while suffering amnesia, and he sees a therapist in “Miami Squeeze” (S5E11).

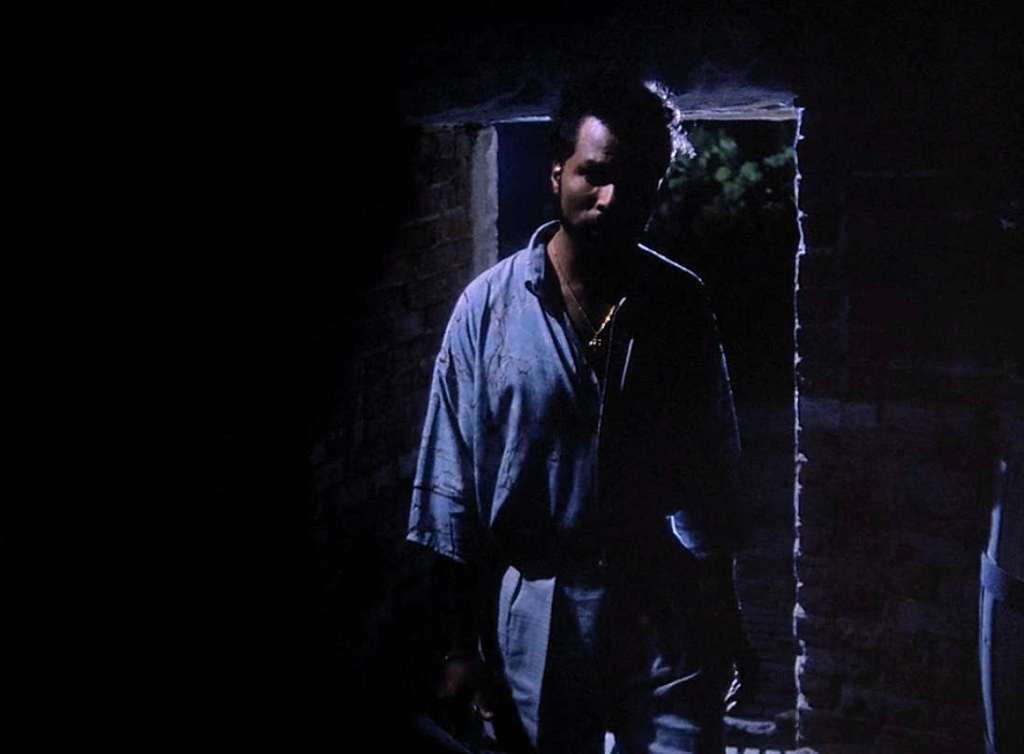

Detective Switek (Michael Talbott) and Vice Squad Lieutenant Castillo (Edward James Olmos) become more prominent in Season 5 to compensate for the frequent absences of Crockett and Tubbs, as in “Heart of Night” (S5E3) and “Borrasca” (S5E5). “Too Much, Too Late” (S5E21) features a nice callback to Switek’s former partner Zito (John Diehl), who was killed in Season 3, when Switek displays one of the snow globes that Zito collected. We also see an aspect of the exhaustive burden of law enforcement reflected in Switek’s gambling addiction, a storyline developed in “Hard Knocks” (S5E8), “Too Much, Too Late” (S5E21), and other episodes but not entirely resolved even in the series finale. Guest characters also demonstrate the different ways burnout can manifest itself, as in “Over the Line” (S5E15), featuring a group of officers who become vigilantes instead of accepting a system that they believe has let them down.

Other themes from earlier seasons are revisited. The big ones are still getting away, as demonstrated by the escape of drug lord Carlos Quintero (Aharon Ipalé) in “Line of Fire” (S5E6), which also continues the theme of interference from federal agencies representing the tough-talking but weak-on-crime Reagan Administration, policies that changed little when George H.W. Bush picked up Reagan’s mantle only one month after “Line of Fire” aired. We’re also still paying the price for Vietnam, with “Asian Cut” (S5E7), perhaps the darkest of the series’ Vietnam-themed episodes. And family continues to be a complication, to be exploited by villains for blackmail or other forms of coercion, or as a source of moral conflicts within criminal families – see “Fruit of the Poison Tree” (S5E9), “Miami Squeeze” (S5E11), and “Jack of All Trades” (S5E12), among others. At least Castillo is still delivering powerful stare-downs.

The series does expand on some of these themes, however, particularly in reminding us that the low level pimps and drug dealers the vice detectives often deal with are not the real villains. Tubbs identifies people of power – primarily referring to politicians and “legitimate” business leaders – as the real criminals in “The Cell Within” (S5E13). And the series anticipates white supremacy and antisemitism, which many of privilege assumed to be a thing of the past, as growing national problems in “Victims of Circumstance” (S5E16).

Not only had the producers and actors of Miami Vice given up, but so had NBC. The network held back four episodes that didn’t air until after the series finale “Freefall” (S5E17) was broadcast in May, 1989. Three of these “lost episodes” aired in June, after the series had gone into summer reruns, but the fourth didn’t air until 1990, when the show went into syndication on the USA Network. NBC chose not to broadcast this last episode, “Too Much, Too Late” (S5E21), because it included an incident of child sexual assault. Unfortunately, key events occur in “Too Much, Too Late” that set up “Freefall”; by airing the episodes out of sequence, viewers were somewhat left scratching their heads over the series’ resolution. And it includes one of the season’s few mentions of Crockett’s deceased second wife.

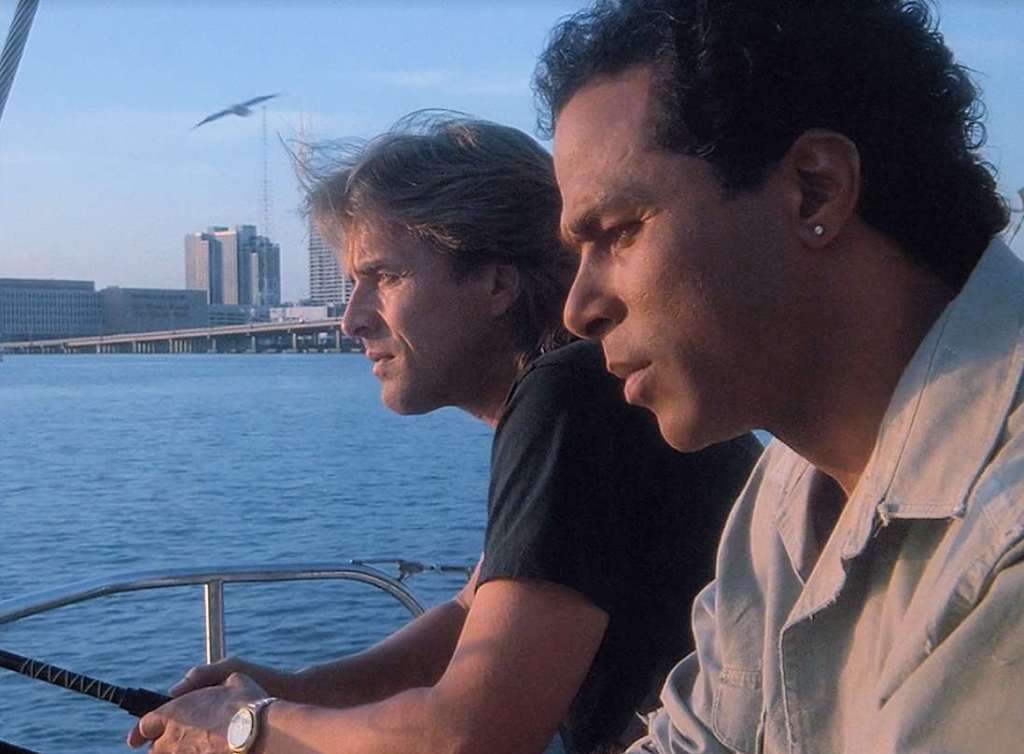

This reference to Crockett’s loss in “Too Much, Too Late,” a reminder of the sacrifice both detectives have made – remember, the series was launched with the death of Tubbs’ brother – occurs in parallel with Tubbs’ proposal to his old flame Valerie (Pam Grier), her third appearance in the series (along with a mention in “The Home Invaders” (S1E19). And it’s crucial in preparing the ground for the characters’ decision to resign in “Freefall.” It’s also significant that they made this decision together, because partnership was always the heart of Miami Vice. Tubbs reminds us of this in “Redemption in Blood” (S5E2), when he tells Crockett/Burnett, “We were friends once. No, we were more than that. Partners.” And “Line of Fire” (S5E6) proves that Crockett also understands, when he says making the world safer for kids is the reason he continues in law enforcement, emphasizing that Tubbs has never let him down, perhaps the only person he can make that claim about.

For two characters who would never have been satisfied with desk jobs but could not realistically maintain the Burnett and Cooper undercover identities indefinitely, ending Tubbs’ and Crockett’s law enforcement careers – at least in Miami – was a sensible choice. By this time the characters understood that they would never overcome the never-ending supply of criminals and that they had saved as many lives as they could. That was the series’ final lesson: Sometimes leaving is the only way to remain alive and sane. There was even a hint of passing the torch to the next generation of vice squad detectives, with the appearance of whipper-snapper Joey Hardin (Justin Lazard) and the prospect, thankfully not pursued, of a Young Criminals Unit spin-off series.

Miami Vice reflected a specific time, and the country was a different place than it had been when the series premiered, having grown as weary with the struggle as the show’s characters. Iran/Contra had fully exposed the Reagan Administration’s hypocrisy regarding crime and terrorism. Like fighting crime in Miami, the U.S. War on Drugs, begun in 1969 and severely escalated during the 1980s, was going nowhere – Pablo Escobar was declared the seventh richest person in the world in 1989. Fashion and music trends change rapidly, and Miami Vice was no longer the trendsetter it had once been. Still, for five years, Miami Vice combined pop culture aesthetics with police procedural melodrama, with enough cynicism to caution anyone tempted to romanticize the past. Miami Vice was a cultural landmark with a moral: We can only complete the journey together. And whatever toll the journey takes, if our intentions are pure, we’ll have cleared a path for a new generation.

Leave a reply to Deliver Us From Evil: The Existential Angst of Miami Vice, Seasons 3 and 4 – The Creative Life Adventure Cancel reply