“Nothing can save Flash Gordon now!”

–Charles B. Middleton as Ming the Merciless, right before Flash is miraculously saved (again), in Flash Gordon’s Trip to Mars—

Life was so much simpler in the old days. Creators of franchise characters didn’t have to worry so much about continuity or canon. They could tell tall tales and audiences were happy to go along for the ride. In the l890s, Sherlock Holmes could fall to his death at Reichenbach Falls, only to return in good health in the early 1900s. In the 1970s, Richie Cunningham’s brother could disappear without explanation and audiences would remain committed for nine more seasons. In the 1980s, Luke and Leia could kiss like prospective romantic interests in one movie and become brother and sister in the next. (Okay, that one doesn’t hold up so well.) And in the 1930s, Flash Gordon’s girlfriend Dale Arden could depart the planet Mongo with blonde hair and reach earth as a brunette.

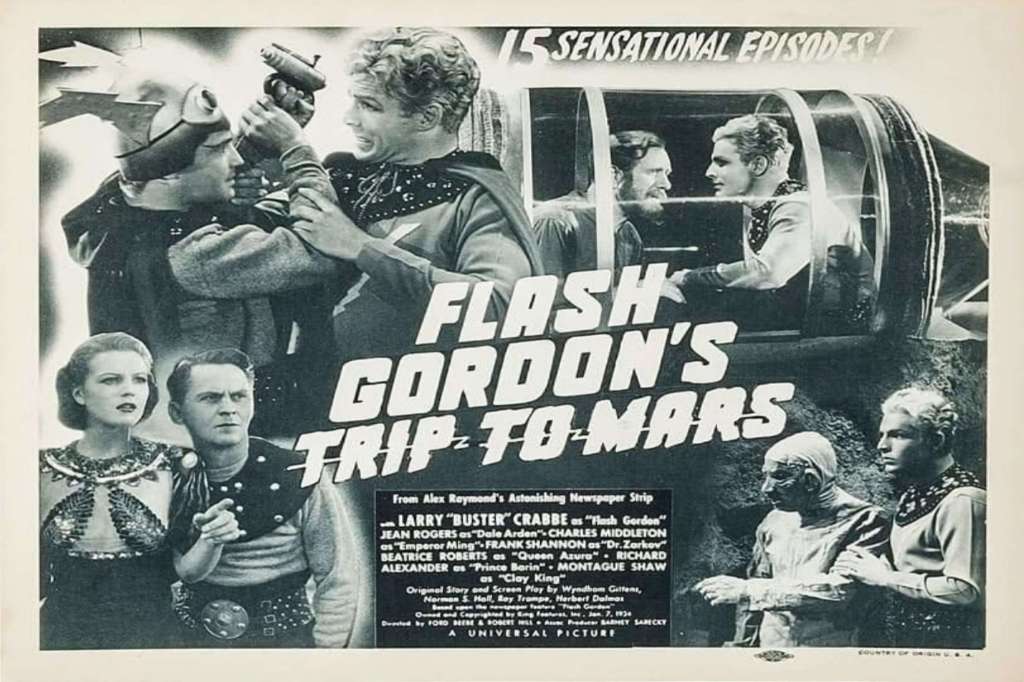

Previously I wrote about the 1936 serial Flash Gordon and its context within the serial or episodic format of pop culture entertainment. Released by Universal Pictures, Flash Gordon was Universal’s second highest grossing film in 1936, prompting a 1938 sequel Flash Gordon’s Trip to Mars. The story was loosely adapted from a 1935 “Witch Queen” storyline in the Flash Gordon comic strip. Unlike the comic, the action in the movie picks up immediately after the events of the first film, with Flash, Dale, and Zarkov returning to earth from the planet Mongo. Now the earth is under threat again: the sinister Ming has teamed up with Queen Azura of Mars to siphon off all of the earth’s nitron, whatever that is, destroying earth’s atmosphere in the process. Only Flash and company can stop them and save humanity. Flash Gordon’s Trip to Mars was even longer than the original, with fifteen weekly chapters and a total run-time of nearly five hours. Like the original, the point was to enjoy the ride, not to tell a complex story with deep character development. The action is reminiscent of Spy vs. Spy, with each side one-upping the other, often due to their own lack of foresight. For example, thank heavens Ming’s Disintegrating Room was designed with a skylight, making it possible for Barin and Zarkov to rescue Flash at just the right moment in Chapter 10. Much like the Death Star was designed with its own fatal exhaust port. It’s all in good fun.

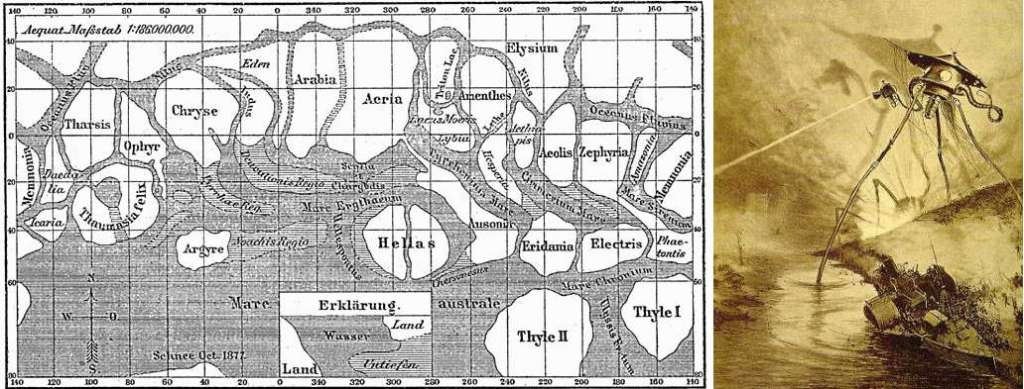

The story as told in the comic strip took place on Mongo. Some have claimed that Universal shifted the movie’s action to Mars to take advantage of “The War of the Worlds” radio broadcast by Orson Welles‘ Mercury Theatre. Except the timing doesn’t work: the first chapter of Flash Gordon’s Trip to Mars hit theaters in March, 1938, while the Mercury Theatre’s “The War of the Worlds” aired in October of that year. A simple explanation is that Mars was already an object of vivid imagination in the public’s mind. The inspiration for Orson Welles’ 1938 radio program, H.G. Wells‘ novel The War of the Worlds, about evil Martians invading the earth, was published in serial form in the 1890s. Edgar Rice Burroughs published A Princess of Mars, the first story to feature another interplanetary adventurer, John Carter, in 1912. Mars’ proximity to earth adds further to its appeal; Venus passes closer to earth but is veiled by constant cloud cover, while the surface of Mars is easily viewed with telescopes, as Galileo did in 1610. Seasonal changes in the Martian polar caps implied a climate potentially similar to earth. Italian astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli observed channels on Mars in the late 1800s; the Italian word “canali” (channels) was translated into English as “canals,” convincing astronomer Percival Lowell and others that an advanced species occupied the planet. The canals were later discredited as optical illusions, but that didn’t stop the public from wanting to believe.

Much of the primary cast from Flash Gordon returned for Flash Gordon’s Trip to Mars. Charles B. Middleton (Ming), Frank Shannon (Dr. Zarkov), and Richard Alexander (Prince Barin) were the most experienced among the cast. All three of them had significant stage and/or screen experience before appearing in the Flash Gordon serials. Buster Crabbe and Jean Rogers also returned as Flash Gordon and Dale Arden. The primary casting weakness is an attempt at comic relief in the character of dimwitted reporter Happy Hapgood (Donald Kerr). Instead of scheming brunette Princess Aura (Priscilla Lawson) from Flash Gordon, we now have scheming brunette Queen Azura (Beatrice Roberts). None of the actors were going to win Academy Awards for their work in these serials. But it doesn’t matter, because the characters are all archetypes of heroes and villains, sidekicks and henchmen, and the actors all commit sincerely to the material.

Of course, most of the production depends on Buster Crabbe’s credibility as the fearless hero. Crabbe may not have been Brando or Olivier, but he clearly had what audiences wanted in a Depression Era Odysseus. A gold-medal Olympic swimmer, Crabbe not only played Flash Gordon, but cinematic versions of Tarzan, Buck Rogers, Billy the Kid, and Wyatt Earp. Crabbe portrays Flash as a true optimist who never hesitates to risk his life for the greater good. When Ming appears to die at the end of Flash Gordon, Flash is a good sport and displays empathy to Ming’s daughter, Princess Aura. In Flash Gordon’s Trip to Mars, he politely addresses Mars’ sinister ruler Queen Azura as “Your Magnificence.” And he doesn’t hesitate to volunteer himself and his colleagues to aid the Clay People, victims of Azura’s magic, in their quest for freedom. Flash’s traits – his earnestness, his confidence, his athleticism, his cleverness at devising on-the-spot rescue schemes, and his endless willingness to negotiate with potential allies – must have made him a perfect American role model as fascist dictators tried to conquer Europe at the tail end of the Great Depression.

What these movies didn’t depend on, thankfully, was a hyper-realistic degree of production design. The many alien species not only all speak fluent English, they mostly look just like humans with eccentric headgear or some other low-budget prosthetic. (The one significant language exception will occur in 1940’s Flash Gordon Conquers the Universe, with Rock People who speak backwards, like characters from a Twin Peaks episode.) This same reliance on the audience’s imagination worked equally well in classics like The Twilight Zone and Star Trek: The Original Series. While the sets and visual effects in Flash Gordon’s Trip to Mars are upgraded from the first serial, and those awkward-looking tight shorts have (mostly) been ditched from the costumes, the wardrobes, flimsy spaceship models, and dated visual effects were plenty good enough to engage audiences of the 1930s. I appreciate the detailed VFX world-building in movies like The Batman (2022) and Godzilla Minus One (2023), but those are examples of well-crafted stories with intriguing characters. Flamboyant visual effects don’t make up for the lazy writing and two-dimensional characters found in some of the DC Extended Snooze-verse movies or – I shudder to even mention them – the Abrams-verse Star Trek disasters. Kids playing with Barbie dolls or Star Wars action figures never needed every visual detail spoon-fed to them, they were (and hopefully still are) perfectly capable of exercising a little creativity. There’s no reason we modern-day movie-viewers can’t do the same.

So we can give thanks that the Flash Gordon serials haven’t been remastered or otherwise tampered with. Crudely colorized versions can be found, but anyone afraid of black and white isn’t ready for Flash Gordon in the first place. The UCLA Film & Television Archive did sponsor a restoration of the 1936 serial from original 35mm negatives, but the look and content of the movie weren’t altered. By contrast, look what they did to the original Star Wars trilogy and the original Star Trek series. No one has convinced me that CGI spaceships look better than the physical models from the old days. I know this is a widely debated topic, and the Star Trek remasters were more about modernizing the look of the TV show, compared to some of the complete visual revisionism of the Star Wars Special Editions. The question that never seems to get answered is: What’s wrong with a movie or TV show reflecting the time in which it was made? What are we afraid of? (Of course, I’m talking about the look and pacing of a production. When racism, misogyny, or other issues come into play, that’s a more complicated discussion. The old days weren’t always better.)

This takes us into overlapping territory with the premise of director’s editions of movies. In the case of the Flash Gordon serials, there are no director’s cuts; directors of these serials weren’t Scorsese-like auteurs but more like employees delivering a product. The first “director’s cut” of a movie appears to have been The Gold Rush, a silent film written and directed by Charlie Chaplin in 1925. Chaplin released a shorter version of The Gold Rush, this time with music and narration, in 1942. But director’s cuts to better reflect a director’s ambition for a film, intended to correct an original release hampered by studio interference, didn’t really take off until the 1970s. That’s partly because of efforts by the Director’s Guild of America in the 1960s to expand the rights of film directors. Some director’s editions, with such films as Blade Runner, The Cotton Club, and The Abyss, are a sincere attempt to get audiences closer to the director’s creative vision. (I’m one of the few people who enjoyed The Godfather Part III (1990), so I’ve put off watching Francis Ford Coppola‘s 2020 recut, The Godfather Coda: The Death of Michael Corleone.) Other director’s cuts, such as the Star Wars Special Editions, seem more calculated to persuade fans to buy another version of a movie they’ve already seen; or, in the case of Zach Snyder’s Justice League, to generate subscribers for the HBO Max streaming service.

It’s also a blessing that the Flash Gordon serials were released before audiences became hostile backseat drivers, fueled by social media platforms and the rise of a right-wing ethos of gaslighting and intimidation. Critics receive death threats if their reviews don’t sufficiently pander to fanboys. Kelly Marie Tran was nearly driven out of the acting business by racists and misogynists after appearing in Star Wars: The Last Jedi (2017), the only movie in the Star Wars sequel trilogy I watched and enjoyed. (And yet, Walt Disney Studios and J.J. Abrams – I really don’t like this guy – seemed perfectly willing to pander to hostile dude-bros and sideline Tran in their muddled “corrective” to The Last Jedi, 2019’s The Rise of Skywalker.) What is discrimination – and toxic fandom in general – but a lack of imagination fueled by fear and ignorance?

Add to that the incessant, frame-by-frame nitpicking of movies on web sites, YouTube channels, and social media, and it feels as if movie fandom has degenerated into gladiatorial combat. Is this why studios feel compelled to release prequel movies of filler material with backstories for every object and character trait? We can only imagine how different the Flash Gordon serials might have been if subjected to such foolishness. Instead, we have these delightful entertainments, with their flat acting, dated effects, and funny-looking costumes. The era-appropriate style of Flash Gordon Goes to Mars only adds to its appeal. Let’s enjoy it while we can, before Amazon buys the IP and unleashes its attack algorithms.

But wait, we’ve had two Flash Gordon serials, and everyone knows all good things come in threes. There must be more to the struggle between Earth and Mongo. Whose technology will win the day? Are the Russians our allies? Will love conquer all? And, seriously, what’s with all the tight shorts? Tune in next time for Chapter 3: Technology, Politics, and the American Way; or, Flash Gordon Conquers the Universe

Leave a reply to docbravard Cancel reply