“We’re all in this together.”

–Buster Crabbe as Flash in Flash Gordon Conquers the Universe—

Three Flash Gordon film serials were released between 1936 and 1940. The world changed a lot during that time. Even though the Nazi Party came to power in Germany in 1933, in 1936 it still wasn’t entirely clear how significantly German expansionism, along with similar designs of Imperial Japan, would impact the entire world, including the United States. By 1940, the tools of war, and the politics of fascism, were a plainly visible threat. This changing world order is reflected in Flash Gordon Conquers the Universe, the last of the Buster Crabbe/Flash Gordon trilogy.

Like Flash Gordon (1936) and Flash Gordon’s Trip to Mars (1938), the 1940 movie was based on the comic strip that had launched in 1934. Released in twelve chapters with a total run-time of 195 minutes, shorter than the two previous entries, Flash Gordon Conquers the Universe has even more flamboyant costumes, more adventurous set design, and a more transparent geopolitical intention. The premise, as always, is simple: Ming the Merciless, emperor of the planet Mongo, once again tries to destroy the earth. This time he deploys a toxic dust called the Purple Death. Flash Gordon, Dale Arden, and Dr. Zarkov return to Mongo, team up with their old friend Prince Barin, and search for an antidote. Plenty of fisticuffs, daring escapes, and flip-flopping allegiances take place along the way.

Buster Crabbe, Charles B. Middleton, and Frank Shannon, as Flash, Ming, and Zarkov, are the only primary cast members to appear in all three films. This time, Barin and Dale are barely recognizable as performed by Roland Drew and Carol Hughes. Drew emotes far more than his predecessor, Richard Alexander, and for some reason looks less like a knight of the Round Table and more like an escapee from Sherwood Forest. And Hughes doesn’t scream or faint as eloquently as Jean Rogers did, but her Dale Arden shows a bit more courage and a lot more jealousy. The dressed-up lizards have returned from Flash Gordon. The Rock People in the middle chapters look suspiciously like Tusken Raiders (or vice versa), and they occupy the Land of the Dead, similar to Planet of the Apes‘ Forbidden Zone. And the requisite anti-Dale this time around is Lady Sonja (Anne Gwynne), helping Ming while serving her own selfish interests.

The distinction between the good girl, submissive Dale Arden, and the bad girls, aggressors Princess Aura, Queen Azura, and Lady Sonja, was obvious throughout the trilogy. While Dale screams and faints much less in Flash Gordon Conquers the Universe than in previous installments, she clearly has two duties: to be rescued by Flash, and to worry about Flash. Her rare moments of independent thinking – commandeering a rocket ship in Flash Gordon’s Trip to Mars, or disarming a soldier in Flash Gordon Conquers the Universe – are still in service to her male superiors. It’s also worth noting that Dale’s wardrobe in Flash Gordon was considered too scandalous by censors, so she is dressed more conservatively in the later movies. In contrast to Dale, the various femme fatales are all suspect precisely because of their independent thinking. Lacking the positive male role model that the women-folk clearly need, they are all foiled in their schemes. Princess Aura’s arc is the most dramatic: she transitions from a plotting temptress in Flash Gordon to the passive wife of Prince Barin in Flash Gordon Conquers the Universe. The men’s attitude toward women is also significant. While Flash gallantly rescues damsels in distress, Ming tries twice – in Flash Gordon and Flash Gordon Conquers the Universe – to force Dale to marry him. In this last film, he rejects his own daughter and reduces her to prisoner-of-war status as a result of her marriage to Barin. Ming also seeks entertainment from an exotic dancing girl, not to mention all those teeming bodies dancing around the temple of Tao. You would never catch Flash in such unsavory company.

The temple of Tao (pronounced tay-oh) shows up briefly in Flash Gordon Conquers the Universe, but the “great god” is primarily mentioned in Flash Gordon. As is common with religion, Tao is primarily a boogey-man for Ming to wield, another tool with which to keep his people in line. Considering the “Orientalism” invoked by Ming’s appearance, Tao comes across as an attempt to associate east Asian Taoism (or Daoism) with villainy. Like our own modern-day oligarchs, Ming tries to associate his power with scriptural determinism: In Flash Gordon’s Trip to Mars, Ming claims, “It is written that the planets shall all be destroyed but one. And the earth shall be first.” Whether this is Ming’s own propaganda or a directive from Tao isn’t specified.

The state of affairs in Europe might explain why the 1940 movie generally ignores Tao, and why much of the action in the first few chapters takes place in the frozen climate of Frigia, with the heroes donning uniforms appropriate to combat in Siberia. The Nazis opened their first concentration camp, Dachau, in 1933. Mussolini’s Italy invaded Ethiopia in 1935, then Hitler invaded Austria, Czechoslovakia, and Poland in 1938-39, initiating World War II. That left the USSR looking like a potentially important ally in the west; FDR had formally recognized Stalin’s government in 1933 and negotiated a trading agreement with them. The USSR also signed a pact with Germany in 1939, setting up Soviet domination of post-war eastern Europe, a pact which Hitler would violate in 1941. So a little western pandering to the Soviets might have seemed like a good idea in 1940. Even Dr. Zarkov’s name sounds Russian, though the movies never develop Zarkov’s origin and ancestry. (Ironically, the skillfully edited avalanche sequence in chapters two and three borrowed footage from the 1929 German film The White Hell of Pitz Palu.)

Zarkov’s primary role is to employ various technologies in service to the cause. He possesses the scientific knowledge of Spock and the engineering know-how of Mr. Scott. And like those Star Trek characters, Zarkov always defers to the leader of the pack. Flash gladly makes use of Zarkov’s technology, whether it’s the rocket ship that makes the whole venture possible, or the Nullitrion that Zarkov devises to attack Ming’s power plant. But technology is only one component of the heroes’ strategy. Forming alliances and good old-fashioned subterfuge are also important. And, more often than not, Flash is happy to embrace the American way: there are few problems that a punch in the face won’t solve. Flash’s identity as a fine, upstanding American lad is also a significant counterpoint to Ming’s foreignness. While the rest of the world is shown to be affected by Ming’s antics, it’s clear that only U.S. leadership would save the day, a premise that would be repeated 56 years later in Independence Day (1996).

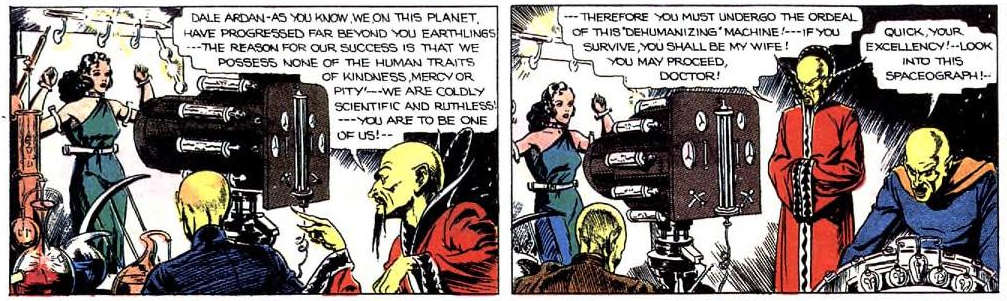

Ming, on the other hand, is a fully committed technocrat, making first-hand use of the technology that he developed himself or with the help of captive scientists (independent contractors!) abducted from other planets. Ming’s cold-hearted reliance on technology is taken directly from his portrayal in the comic strips. To make the distinction between Ming and humanity even more explicit, he uses a “de-humanizer” in Flash Gordon, and his ally Princess Azura uses “incense of forgetfulness” in Flash Gordon’s Trip to Mars. Ming’s threatened invasion from above may not have seem farfetched to 1940 audiences. Rocket-like artillery had been used in combat since at least the 1600s, but development of rockets with the intention of traveling to space – and to deliver more powerful explosives – accelerated in the early 1900s, with the U.S., Germany, and the USSR making significant advancements in the 1920s and 1930s. And the Purple Death calls to mind chemical warfare, specific forms of which had been banned by the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907. That didn’t stop the French use of tear gas in World War I, along with much deadlier use of multiple toxins by the Germans. Estimates put chemical warfare deaths during World War I at anywhere from 500,000 to well over one million. Death from the sky, in multiple forms, was a valid concern in 1940. As good science-fiction so often does, the Flash Gordon serials addressed genuine anxiety about the present through metaphors of space travel and extraterrestrial conflict. Unlike a lot of science-fiction, however, the Flash Gordon stories cleverly set the action in the present day, using alien worlds to create a futuristic ambience.

The bad guys are always the first to unleash a robot army. That’s the lesson Ming demonstrates in Chapter 3 by deploying his walking bomb army of Annihilatons. Basing his kingdom, his entire existence, on technology, intimidation, and imprisonment, Ming seals his own fate. This also explains why Ming’s army is a gang of incompetent bumblers, while Flash’s colleagues are so accomplished. Flash succeeds through a combination of his own courage and the loyalty he obtains from friends and allies, while Ming can only sleep securely in a room with an electrified carpet for protection. Ming’s scientists and soldiers are under constant threat, and they will betray him in the end. Yes, there are also risks in allowing Flash Gordon to “conquer the universe” – Flash is not an elected official and represents the earth only because of his accidental encounter with Zarkov in Flash Gordon – but we can at least be comforted that Flash depends on a network of allies who will keep him on the straight and narrow. That framework of cooperation would be equally important in Star Trek and Space: 1999, among others. We often remember historic figures as either bad – Hitler, McCarthy, etc. – based on their selfishness, or good – MLK, Obama, etc. – due to their generosity of spirit. As Flash reminds Barin in Flash Gordon Conquers the Universe, “We’re all in this together.” That philosophy is the only way we can save ourselves, and it was as important in the 1930s as it would be to future generations.

Leave a reply to docbravard Cancel reply