If you enjoy this essay, please share it on your favorite social media platform so others can discover my work.

A Big Stick

“Palo Alto is a bubble. I do know that now, but it’s an important bubble for the twentieth century, and a thorough accounting of the town’s role explains a lot about California, the United States, and the capitalist world, where it has found itself elevated to the status of promised land.”

—Palo Alto by Malcolm Harris–

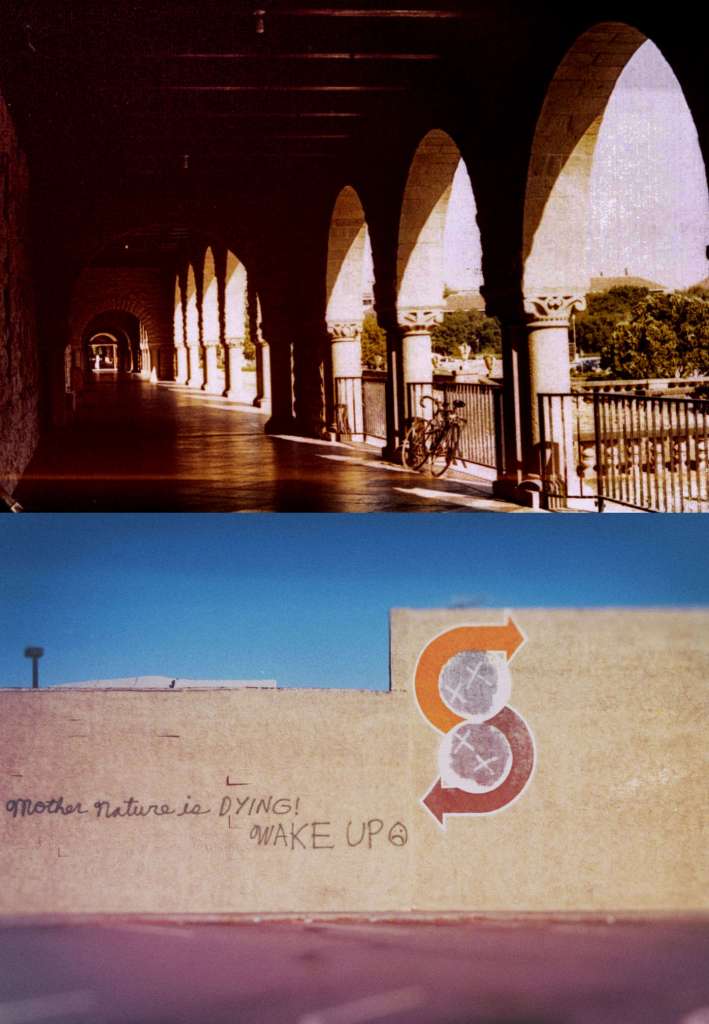

I’ve looked forward to reading Palo Alto: A History of California, Capitalism, and the World by Malcolm Harris since it was released in 2023. I put it off for a while: the book is 600+ pages and, considering where blind faith in capitalism has taken us, I didn’t anticipate an uplifting read. It’s a conflicting topic for me. I lived in Palo Alto – home to Stanford University and Hewlett Packard, among others – for several years during the 1990s. (The city is named after a 1,084-year-old Redwood tree, El Palo Alto, Spanish for “the tall stick.”) In many ways, it was one of the best places I’ve ever lived. I was in Silicon Valley when consumer access to the Internet and the World Wide Web was still a new and growing thing. Fresh out of business school, I was still naive enough to think that the titans of tech actually believed their utopian propaganda. Meanwhile, it was easy to be seduced by the comfortable climate, plentiful regional transit, weekend afternoons at Kirk’s Steakburgers and Know Knew Books on California Avenue, summer jazz concerts at the Stanford Shopping Center, and cycling on my favorite route through the foothills, a route that included Sand Hill Road, where the venture capital gurus have a surprisingly subtle presence, and Page Mill Road, home to HP’s world headquarters. The 1990s was a transformative time for me personally, and for the world. Developments in Silicon Valley had a lot to do with that.

Graduate business school cautioned me about Silicon Valley before I arrived, though I was too dimwitted to realize that at the time. One professor advised his students to enter the workforce as sharks, because we would be swimming among sharks. Required reading in another class was Tracy Kidder‘s 1981 Pulitzer Prize winner, The Soul of a New Machine, an account of development of the MV/8000 32-bit minicomputer at Data General Corporation. Massachusetts-based Data General is long-since defunct, absorbed by Dell EMC, its demise one component in the westward migration of tech industry power. But the narrative was a clear prelude to what I later observed in the Valley: managers set employees in competition not only with other companies, but with each other; programmers and designers work grueling schedules to be first to market with a potentially substandard product; a few people get rich while employees hope for future rewards and customers struggle with buggy machines. Prioritize competition over cooperation and process over people. Data General manager Tom West ruled employees with the “mushroom theory of management“: “keeping them in the dark, feeding them s–t, and watch them grow.” We business students were expected to be impressed, yet it’s not hard to imagine the outcome of this archaic practice: Similarly isolating leaders gave us the sinking of the Titanic and the bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers. Of course, I understood none of this at the time. I swallowed the propaganda, graduated, and headed to the San Francisco Bay Area in the early ’90s, about as un-shark-like as I could be. Like a shadowy Tom West, my first boss frequently put employees on conflicting paths, right before disappearing from the office for days or weeks at a time to avoid the inevitable chaos.

East and West

“…a generic formula: Anglos rule; all natives are Indians; all land and water is just gold waiting to happen.”

—Palo Alto by Malcolm Harris–

The fact that we referred to Palo Alto as “Shallow Alto” indicates that the conflict was clear even then. The magnitude has deepened, but housing prices were already sky high. The first time a Palo Alto house sold for over $1 million – around 1997 or 1998, if memory serves – even the rich folks blinked. The entrenched elitism was generally ignored by those of us living through it. That was easy to do if you avoided East Palo Alto; bordering Palo Alto, but in a different county (from Santa Clara to San Mateo) and so socioeconomically outclassed that the border between the cities was a visible line across the land – a smoothly paved road became cluttered with potholes, houses looked run down, and no bank or big box store would open shop there. East Palo Alto was the “murder capital of the world” in 1992, with the highest per capita murder rate in the country among cities of similar size. Bay Area home buyers, with increasingly limited options, soon began buying and renovating East PA properties, initiating a transformation that resulted in escalating home prices and zero homicides in 2023. It was a free market miracle! Of course, some social and educational inequity remains; as Harris points out, someone has to work the thankless retail jobs. According to Zillow, at the time I write this, the average home price in East Palo Alto is $1.0 million. And if that seems pricey, consider the average price right next door in Palo Alto is $3.4 million. That’s even higher than San Francisco.

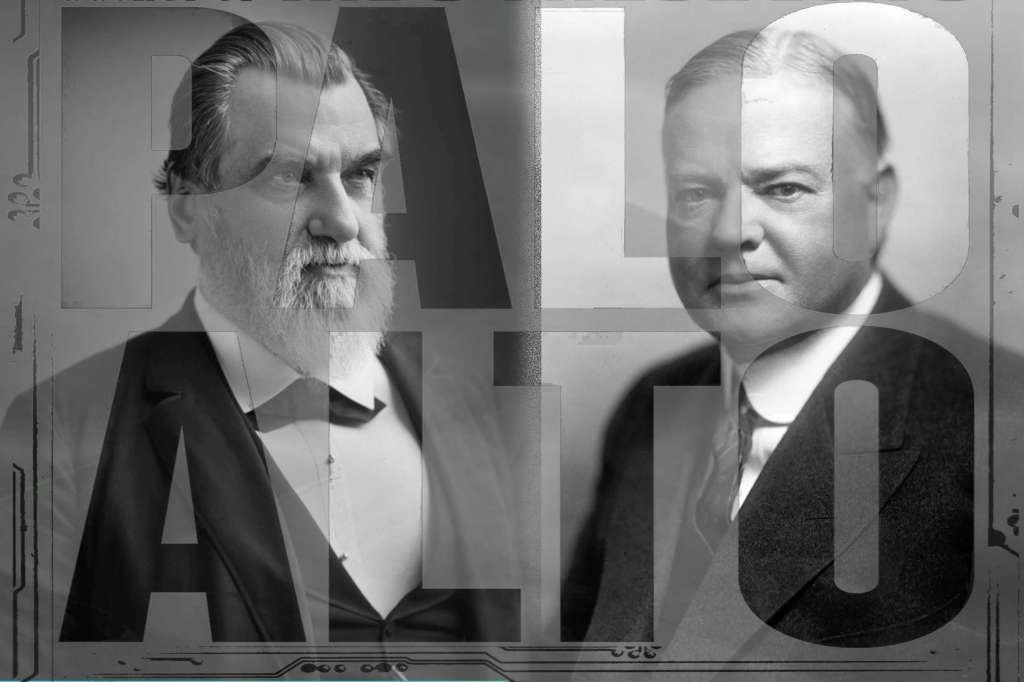

That separation – bifurcation is the term Malcolm Harris uses repeatedly – was not an accident, but a result of redlining and other racist tactics of the nefarious California Association of Realtors and other right-wing organizations. Bifurcation is a common theme throughout Palo Alto and can partly be traced back to the work of such privileged folks as Leland Stanford, founder of Stanford University, and David Starr Jordan, the university’s first president. Establishing the pattern that still guides Silicon Valley, Leland Stanford had a long history of grifting and exploiting the work of others. His work breeding trotting horses inspired some of the technological and artistic achievements of Eadweard Muybridge, a history brilliantly described in Rebecca Solnit‘s book River of Shadows: Eadweard Muybridge and the Technological Wild West, which makes an excellent companion read with Palo Alto. In conducting time-motion studies for Stanford, pioneering photographer Eadweard Muybridge thought he was engaged in the simultaneous creation of both knowledge and art. But Stanford’s goal was to breed the most efficient trotting horses possible, maximizing profit and overlapping considerably with the principles of eugenics. David Starr Jordan, meanwhile, was an admitted eugenicist who recruited another eugenicist, Ellwood Patterson Cubberly, to head Stanford University’s School of Education, leading to a sequence of hiring and “research” that eventually gave us the Stanford-Binet “intelligence” test, a self-selecting method of IQ testing designed to weed out exactly the people most feared by Jordan, Cubberly, and others of their kind. Both Leland Stanford and David Starr Jordan sought to divide the world – as early and as frequently as possible – into those they considered worthy of investment and those they did not.

White Man’s Burden

“Silicon Valley has never been interested in slow and steady growth — an early winning appearance is key to the Palo Alto System.”

—Palo Alto by Malcolm Harris–

Human augmentation has been a strong motivator in Silicon Valley ever since. Initially taking the form of education, nepotism, and selective breeding (Stanford education professor, Lewis Terman, one of the folks behind the insidious IQ testing, used test results to identify a prospective mate for his son), it wasn’t long before computer hardware and software entered the picture. Despite the myth of hyper-achieving superstars, the goal of human augmentation wasn’t about individual achievement, but growth of capital, the same quest for profits that drove the transcontinental railroad and trotting horse breeding (Leland Stanford had his hands in both), as it would later drive avionics, social media, artificial intelligence, and just about every single event in Santa Clara County ever since. It was the same thinking that drove William Shockley Jr. (also an acknowledged eugenicist) when he improved the efficiency of bombing campaigns during World War II. Shockley’s research was helpful in defeating the Nazis, which was important not because they were Nazis, but because they were disrupting global trade. However, by reducing military combat to a simple balancing of man-hours vs destructive outcome, Shockley – by then a Stanford professor – helped pave the way for the United States’ apocalyptic bombing of North Vietnam, which killed a lot of people and made a handful of individuals rich off government defense contracts.

Much of William Shockley’s success derived from being born into the best connections a person could ask for, the son of both a Stanford professor, his father, and a Stanford graduate, his mother. What Shockley and these other white men – they were almost all white men – never acknowledged was their extraordinary good luck. Another fact of life in Silicon Valley is the blind eye that’s turned to the significance of being in the right place at the right time, of knowing the right people, of being born white or wealthy or into some other fortunate set of circumstances. The Combine – rich men who supported development of the transcontinental railroad through a series of shady economic arrangements – didn’t choose Leland Stanford as their president because he was the smartest of their group, but because he was the most effective mouthpiece for their propaganda. A later group of white men – meeting at Stanford’s Hoover Institution, founded by Stanford graduate Herbert Hoover – would choose Ronald Reagan and George W. Bush as puppet-presidents for much the same reason. Similar luck is behind the fortunes of recent generations of tech oligarchs. Of the two Steves behind Apple Computer, Wozniak was the technical expert. Jobs, with no technical skill worth mentioning, was the bully who invented nothing but took most of the credit. Bill Gates – based in Seattle but Stanford still has a building named after him – may have been a clever lad as a teenager, but he really succeeded because he attended Seattle’s private Lakeside School in the late 1960s. Lakeside offered Gates two exclusive benefits: he met Paul Allen, his future Microsoft co-founder, and he had access to a DEC mainframe computer, thanks to fundraising by the Lakeside Mothers Club. Another textbook example is the luck experienced by Ramesh “Sunny” Balwani, the salesman and Stanford drop-out who joined web-auction startup CommerceBid at just the right time to receive a massive windfall when CommerceBid was sold to Commerce One. From Palo Alto: “It was a very lucky series of events, but as the reporter John Carreyrou writes, ‘Sunny didn’t see himself as lucky. In his mind, he was a gifted businessman and the Commerce One windfall was a validation of his talent.’ This was a common affliction among the Bay Area’s new millionaires; it’s hard to convince a guy on third base that he didn’t hit a triple.” Maybe that luck was with Balwani when he began a prison sentence for his role in the Theranos fraud case.

Feed the Rich

“The impersonal drive animating those big men in suits wasn’t the people’s hunger for bread; it was capital’s hunger for profits.”

—Palo Alto by Malcolm Harris–

Funding – whether of the public variety that enriches defense contractors, or the private variety that educates rich kids like Gates and funds startups like Theranos – is another essential component of the Palo Alto story. As Harris describes in Palo Alto, capital amounts to an impersonal force that will always seek maximum profits. Riding on the backs of taxpayers is a straightforward way to achieve that, and we can thank Herbert Hoover for the public-private cartels that manage nearly every sector of our economy. One early example of this is Hoover’s role as director of the U.S. Food Administration during 1917-1918. President Woodrow Wilson gave Hoover extraordinary power to act as the country’s “food dictator,” managing the national food supply during World War I. Hoover staffed the department with representatives of the food processing industry, lowering prices farmers received while increasing profits for the food processors. “He earned the ire of the staple-farmer populists, the loyalty of the processing industries, and the admiration of anyone who believed what was printed in the corporate press. America won the war, and the boys came home with an appreciation for canned food and candy. Rather than scale down mass production when soldiers went back to their local food systems, the processors plowed their wartime profits into advertising designed to convince the country that processed foods from national companies were better and safer.” Hoover followed a similar model of government support for a private cartel to expand the nation’s home-building industry by “creating long-term amortized mortgages, lowering interest rates, offering government aid for private housing for the poor [that part didn’t turn out so well!], and reducing construction costs.” This has become the de facto model throughout the U.S. economy, particularly the resource-devouring military-industrial behemoth. And for all the misguided paranoia about alleged shadow governments, the aforementioned Hoover Institution has pulled a lot of strings on behalf of the very wealthiest among us, blocking rational responses to climate change, public health crises, nefarious tax policies, and other situations.

It may seem odd to speak of suit-and-tie “captains of industry” like Herbert Hoover and William Shockley interchangeably with khaki- and sweater-wearing technogeeks like Bill Gates and Steve Jobs, or the current generation of microdosing posers, but they are all cut from the same cloth of augmentation, bifurcation, rapid and reckless growth, and obsessive competition for artificially scarce resources. Herbert Hoover would have gotten along just fine with the likes of Bezos and Zuckerberg. A cultural shift – from college athletics and at least an illusion of public service as military officers or politicians, to a post-Vietnam era free from any pretense of public service or team spirit – explained the superficial differences. “These repellent young men were the tools that got capital from the crisis of the 1960s to the ‘greed is good’ ’80s, and an unwillingness to wash and feed oneself began to seem indicative of programming skills and economic value.”

Chess Moves

“The children of California shall be our children.”

–Leland Stanford on the creation of Stanford University–

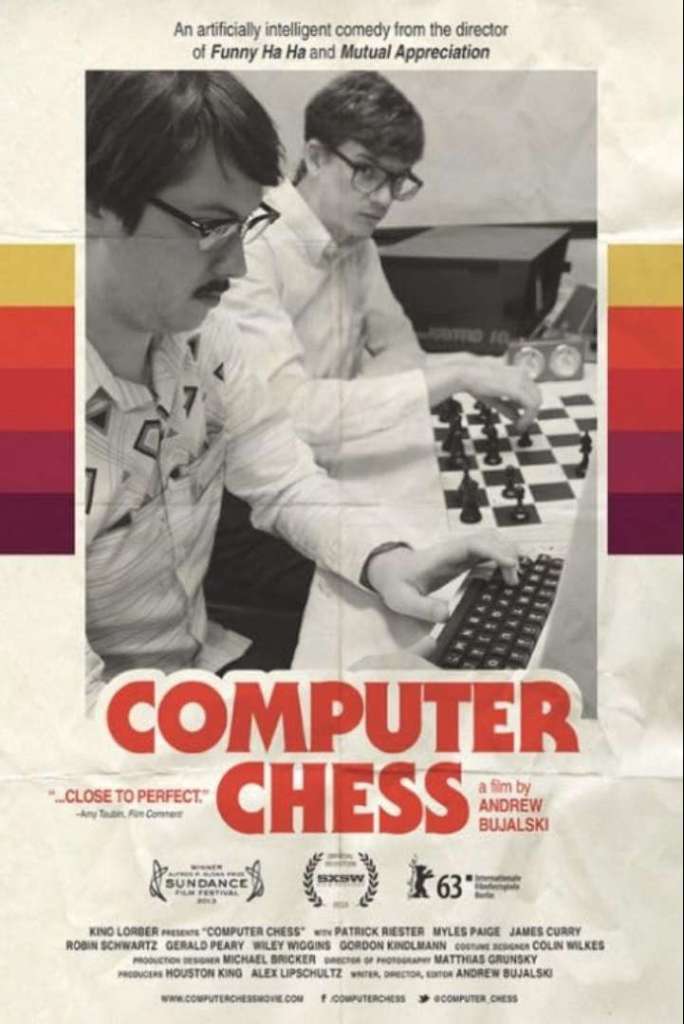

This generational suit-to-sneakers transition is captured in the 2013 movie Computer Chess, directed by Andrew Bujalski. Bujalski is considered the “godfather” of mumblecore after directing Funny Ha Ha (2002), widely regarded as the first true mumblecore film, but heavily influenced by such iconic dialogue-heavy predecessors as My Dinner with Andre (1981), Stranger Than Paradise (1984), and Before Sunrise (1995). The premise of Computer Chess – which resides firmly in mumblecore territory – is straightforward enough: In 1980, computer nerds from around the country gather in an unnamed California city to determine who has the most robust computer chess program. The entire production is a series of awkward encounters and debates loaded with apocalyptic undercurrents. The event is administered by a bossy, older chess grandmaster who tries unsuccessfully to keep a tight grip on the youthful, casually dressed programmers. The grandmaster sees events in terms of if and when a chess program will be able to defeat him, but it’s clear that his stuffy attitude will not prevail much longer.

In a Computer Chess subplot, one of the programmers engages uncomfortably with an older couple from a couples’ spiritual retreat taking place at the same hotel. Advanced technology and profit manipulation may seem a contradiction in a land known for new age spirituality, but, again, the purpose is one of human augmentation in a land that has always attracted misfits and outliers. All that maximal efficiency thinking didn’t just apply to the workplace, it carried over into lifestyle. And for super-achievers, “lifestyle” means a lot more than trendy fashions and home decor. That’s why Leland and Jane Stanford tried to communicate via seance with Leland Stanford Jr., their teenage son and the university’s namesake, after his untimely death from typhoid fever. It explains how Silicon Valley and the movie industry could exist in the same state. It’s also how we got Hewlett Packard in Palo Alto and the Human Potential Movement‘s Esalen Institute in nearby Big Sur. When I worked for a tech-oriented market research provider in Silicon Valley in the ’90s, we briefly shared office space with a yoga group that aspired to literally take flight in the midst of meditation sessions. When they moved out, they left behind a room full of pillows and, to the best of my knowledge, no successful flights. But we were all positioned well within the growth potential mindset. From there, it’s a short jump to Goop, Soylent meal replacements, and other such snake oil purveyors. The best spirituality is always profitable.

The Continuous Present

“Eventually, capital will withdraw from Palo Alto. Given its druthers, capital will use the place up until it’s no longer worth the trouble. Since capitalists like living in the Bay Area, by the time they’re finished with it they’re likely to have exhausted much of the rest of the planet.”

—Palo Alto by Malcolm Harris–

Capital’s relentless pursuit of profit is the common thread and it is the proof that we humans sacrificed ourselves long ago to inhuman, even inorganic, principles. Luck placed certain individuals in the right place and time to exploit these forces, but the names and faces are essentially interchangeable. If Bill Hewlett and David Packard (both Stanford graduates) hadn’t started selling low-cost oscillators in the build-up to World War II, someone else would have. One visit to the area and it’s easy to see how Leland Stanford and everyone who followed him wanted to settle in and try to strike it rich, a multitude of faces hoping to bubble up and join the fortunate few. Generations of people from around the world have sought a better life in Palo Alto and the San Francisco Bay Area, and not all of them have sold their souls. Propaganda only works if it has at least a grain of truth, and along with the business magnates and tech bros, edgy artists and groovy musicians joined the migration. While Stanford was cranking out faux libertarians, counter-culture elements in nearby Berkeley held out against development of People’s Park for 55 years. Despite the stultifying “Sillyclone Valley” illusion of culture, genuine culture persists even today. Even with the apocalyptic direction the new human machines have taken us, I still remember my days in Palo Alto as some of the best of my life. Kirk’s Steakburgers had to move from California Avenue, but they’re still hanging on in Palo Alto. Malcolm Harris’ Palo Alto isn’t exactly light reading, but it’s far more impressive than I anticipated. This essay only scratches the surface of the book’s contents, and I rank it with Robert Caro‘s The Power Broker as a defining text of U.S. history. Harris ends his book by speculating that perhaps the only viable solution is to return Stanford University’s 8,100 acres to the original inhabitants, the Ohlone people of California. Even most self-proclaimed progressives would reject such a humane option. But if I ever have the chance to vote on that plan, you can count me in.

Leave a reply to Kalyanasundaram Kalimuthu Cancel reply