This essay is part of a series exploring movies that are problematic but popular. Title suggestions are welcome in the comments or via the Contact Me page. If you enjoy this, please share it on your favorite social media platform to help other readers discover my work.

“Today, some conservatives idealize the 1950s as a time of moral clarity, patriotism, family stability, and traditional values, a time to which America should return. But that 1950s never actually existed. What looks to them like moral clarity was actually well-masked racism, sexism, and economic oppression.”

–Scott Miller, Sex, Drugs, Rock & Roll, and Musicals—

My parents forbid me from seeing Grease when it was released in 1978. That put me well out of step with my peers – Grease was the highest-grossing movie of the year, the highest-grossing musical film up to that point, and the soundtrack was the second best-selling album of 1978, behind another John Travolta music-fest, Saturday Night Fever (1977). Grease was something of an anomaly that year, which might explain some of its popularity; other top-grossing films in 1978 included Superman, National Lampoon’s Animal House, Jaws 2, and The Deer Hunter. I finally saw Grease during college in the late 1980s. I loved it immediately and, while my assessment of the movie has changed over the years, I still love it. But should I?

Grease began as a stage musical in Chicago in 1971. The show moved to New York City in 1972 and opened on Broadway later that year. Preceded by Hair in 1967, and followed by Jesus Christ Superstar in 1971 and The Rocky Horror Show in 1973, Grease was part of a wave of anti-establishment theater productions that broke from traditional musicals, using rock music and raw storylines to celebrate self-expression and freedom from authority. The original production was not subtle about its sexuality and reflected the ethnic diversity in the working class Chicago neighborhood of the play’s co-author Jim Jacobs, who based the play on his years as a student at the Windy City’s William Taft High School. The film adaptation made a number of revisions to the play, including replacing the song “All Choked Up” with “You’re the One That I Want,” changing Sandy Dombrowski to Sandy Olsson, and changing class geek Eugene Florczyk to Eugene Felsnic.

“Devotees of the original, such as choreographer Patricia Birch (who had studied under Martha Graham and Agnes de Mille and was one of the original dancers in West Side Story on Broadway), watched as their beloved salty musical was frothed into a sweet milk shake.”

—Vanity Fair, 26 January 2016–

A film adaptation of Grease was not really a tough decision in 1978. The play was insanely popular, running for 3,388 performances on Broadway before closing in 1980. Nostalgia for the 1950s was in the zeitgeist. American Graffiti, set in 1962 but clearly reflecting a 1950s vibe, was released in 1973; Happy Days aired on ABC from 1974 – 1984, alongside Laverne & Shirley from 1976 – 1983; The Lords of Flatbush (1974) was set in 1958 and featured Sylvester Stallone and Henry Winkler. The ’50s-revival group Sha Na Na – who, believe it or not, “delighted and bewildered” the hep cats at Woodstock – had a syndicated TV series from 1977 – 1981 and appear briefly in Grease as Johnny Casino and the Gamblers. To mainstream America, the Eisenhower years seemed awfully appealing after the double-fiasco of Vietnam and Watergate. For all the parental hand-wringing over Elvis Presley’s hips in the fifties, Elvis looked positively tame compared to the disco and punk bands that were popular by the mid-seventies.

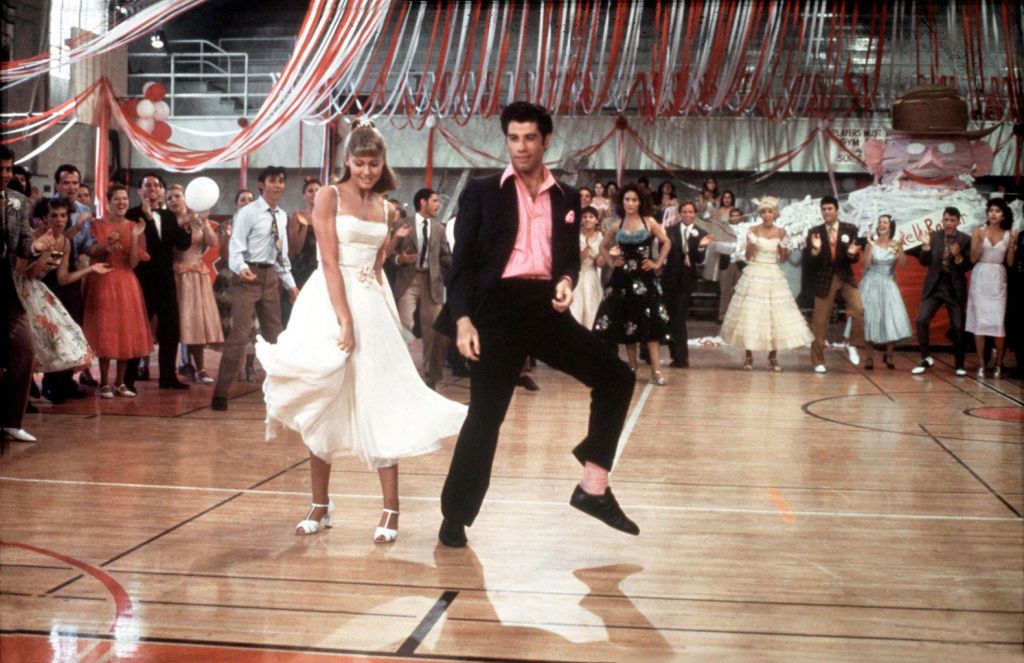

Despite a reduction to PG status (my hyper-conservative parents never explained their opposition) and moving the action from Chicago to the suburbs, the movie softens the edges but generally recreates the play’s storyline: The T-Birds and the Pink Ladies navigate a series of personal melodramas during their final year at Rydell High School in the late 1950s. Will Kenickie (Jeff Conaway) get his car in race-worthy condition before the school year is over? Is Rizzo (Stockard Channing) really pregnant, and will she and Kenickie stay together? Will T-Bird leader Danny Zuko (John Travolta) overcome his insecurity and declare his love for Australian transfer student Sandy (Olivia Newton-John)? Will Frenchy (Didi Conn) return to high school or remain a beauty school dropout?

Liberation from sexual repression was the main point of the play and the movie (oh, that’s what my parents didn’t like!), and there are loads of symbolism and double-entendres toward this end. All of the characters’ conflicts are resolved by the end credits and viewers are sent off with a rousing musical number. Some choices are made along the way that today seem…let’s say questionable: the actors are all clearly older than their teenage characters (Stockard Channing was the oldest “teenager” at age 33); a fairly trim-looking Jan (Jamie Donnelly) is labeled fat; it sure looks like National Bandstand host Vince Fontaine (Edd Byrnes) plans to take advantage of Marty (Dinah Manoff) by spiking her soft drink; the climactic action involves a life-threatening drag race; and the movie ends with Sandy and Danny sailing off in a flying car that isn’t Herbie the Love Bug or Chitty Chitty Bang Bang. The most dramatic character arc, of course, is Sandy’s transition from good-girl “Sandra Dee” to leather-clad, cigarette-smoking Sandy. (Marie Osmond was offered the role but turned it down precisely because she objected to Sandy’s “rebirth.”) The message seems to be that a girl should change her entire personality to catch a guy. The end result is a movie that, today, we probably shouldn’t love.

“In a few moments, the entire nation will be watching Rydell High. God help us!”

–Eve Arden as Principal McGee, Grease—

The flying car finale is not such a serious outlier: the scene bookends the movie with the animated opening credits – featuring a song written by Barry Gibb and recorded by former teen sensation Frankie Valli – creating a dream-like quality appropriate to a movie about overage teenagers who habitually burst into song. But some of the points above I can’t defend. Drink-spiking and body-shaming may have been acceptable jokes in 1978, but they shouldn’t have been. Smoking is presented as “cool” but it definitely isn’t. Motor vehicle crashes were, and still are, one of the leading causes of teenage fatalities in the U.S. These are serious matters that should not be dismissed. That makes the film unwatchable for some and with good reason.

Still, for those willing to look, Grease is deeper than a simple youth musical, and that’s the premise I’m here to argue. A lot of the movie’s success has to do with the cast; in hindsight, it’s hard to imagine anyone else in these roles. Eve Arden brings the perfect balance of tolerance and exasperation as Principal McGee. Sid Caesar is a mountain of patience as Coach Calhoun, calmly redirecting Zuko’s clumsy athletic efforts. As for the age of the “teenage” actors – pshaw. This is a long-standing tradition in Hollywood. Just look at the aforementioned Happy Days and American Graffiti for textbook examples. Jon Heder was 25 when he filmed the 16-year-old lead in Napoleon Dynamite. Jonah Hill was 23 when he played a high school senior in Superbad. Steve McQueen was 27 when he played a teenager in The Blob, which filmed in the summer of 1957. Sure, Stockard Channing was 33 when Grease filmed, but she’s Stockard Channing, so who cares? Her performance as the blustery but insecure Rizzo is spot-on.

“Grease opened up a whole other world for me. It gave me the opportunity to reinvent myself.”

–Olivia Newton-John, Billboard, 14 April 2018–

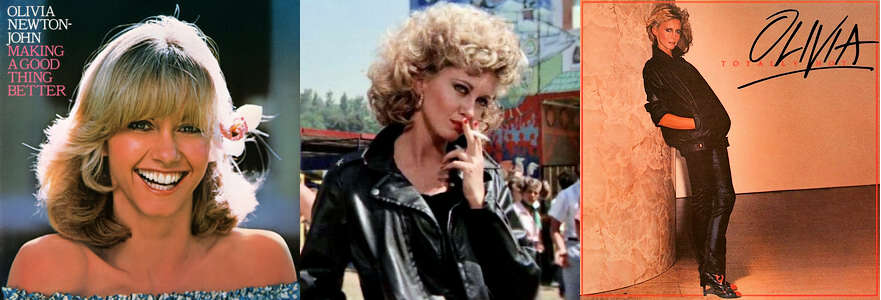

The rest of the cast fills their roles equally well. John Travolta had not only played a minor role in the Grease Broadway production, but he was already playing a T-Bird type on network television as Sweathog Vinnie Barbarino in Welcome Back, Kotter, and he would soon rise to superstardom in the wake of 1977’s Saturday Night Fever. Olivia Newton-John had recorded a series of pop-country albums but jumped at the chance to follow Sandy’s path, dressed in black leather on the cover of her first post-Grease album, Totally Hot. (ONJ took the image even further in 1981, with “Physical,” a song originally written with a male vocalist in mind.) Jeff Conaway had played Danny Zuko on Broadway before accepting the role of Zuko’s best friend Kenickie in the movie; the hot rod song “Greased Lightning” was performed by Kenickie on Broadway, but Travolta wanted the song for his character in the movie: “And because I had clout, I could get the number.” The Zuko-Kenickie rapport, two young men who want to be more expressive in their friendship but face generations of gender role constraints, only works if the actors generate the right on-screen chemistry, and Travolta and Conaway get it just right.

Some of the supporting roles didn’t have a lot of screen time but reminded viewers of Grease‘s DNA as a musical and a teen romance. Teen Angel Frankie Avalon really was a teen angel, recording hit singles in his late teens and early twenties before appearing in a series of beach movies with Annette Funicello, starting with Beach Party in 1963. Joan Blondell, as beauty school instructor Vi, traced the lineage even further back; Blondell began her career in vaudeville and such musical films as Footlight Parade (1933) and Gold Diggers of 1933 (1933). Edd Byrnes, as Vince Fontaine, had played youth-friendly Kookie Kookson on the TV detective series 77 Sunset Strip. These youth-entertainment veterans placed Grease within a larger pop culture context and gave this next generation their blessing to chart a new course.

“Little Sandra Dee isn’t supposed to smoke, you know. Or drink. Or breathe.”

–Sandra Dee, 1967–

That through-line – a teen musical set in the 1950s, influenced by the sexual revolution of the 1960s, produced in the tail end of second-wave feminism and the lead-up to Reagan conservatism – was made even clearer by evoking Sandy’s name-sake in the song “Look at Me, I’m Sandra Dee”: “I don’t drink or swear / I don’t rat my hair / I get ill from one cigarette…” Rizzo sings to poke fun at squeamish Sandy. Born Alexandra Cymboliak Zuck and raised in the Russian Orthodox Church, Sandra Dee appeared in occasional dramas but was best known for innocent roles in musicals and romantic comedies like the pre-Beach Party beach party film Gidget (1959), Come September (1961), and Tammy and the Doctor (1963). Dee’s public image was highly guarded to maintain consistency with her screen roles and, sometimes, to avoid tarnishing her troubled, seven-year marriage to Bobby Darin. (See my essay “Reeling with the Feeling” for a little background on Bobby Darin.) “…adults loved Sandra Dee,” New Line Theatre founder Scott Miller wrote, “she reassured them that their teen was a ‘good girl.’” But Dee’s public image was as false as most 1950s nostalgia.

Dee was born in 1944, but her mother claimed a birth year of 1942 so Dee could make an earlier start at a modeling career. Her parents divorced and in 1950 Dee’s mother married real estate magnate Eugene Douvan, who told his stepdaughter, “I’m not marrying your mother. I’m marrying both of you.” Douvan sexually assaulted Dee repeatedly during her childhood. She struggled with anorexia, alcoholism, depression, and, ultimately, serious physical health problems by the time she reached her forties. Dee was only 62 when she died of kidney disease, after four years of dialysis. We know nothing of Sandy’s home-life in Grease, this isn’t that kind of movie, but we know the kind of phoniness and sexual repression she hopes to escape. “Look at me, there has to be / Something more than what they see / Wholesome and pure, oh, so scared and unsure…” she sings late in the movie. “Sandy you must start anew / Don’t you know what you must do…” Sandy’s liberated self isn’t to attract a guy, but to explore her own potential. And her new image at the movie’s end isn’t really unexpected – just look at Sandy’s enthusiasm during the National Bandstand dance contest. This is clearly a character who wants to cut loose. She can always go back to sweaters and poodle skirts, but at least she’ll be guided by her own life experience.

“If Travolta lacks the voltage of Elvis Presley (his obvious role model for this film), at least he’s in the same ballpark…”

–Roger Ebert reviewing Grease on its 20th anniversary–

What is less obvious in Grease, and the character arc that is rarely discussed, is Danny Zuko’s self-improvement. A big chunk of the movie’s middle act shows Zuko’s efforts to fit into Sandy’s uptown world. He says very clearly that he is trying to change. It turns out to be a lot harder for Zuko to adapt to Sandy’s world than vice versa, but he does change. Have you forgotten that Zuko shows up wearing a varsity athletic sweater at the end of the movie? It’s a striking visual – Zuko still identifies with the leather-jacket crowd, but he’s now separate from them. Zuko’s interactions with Kenickie also show a young man who aspires to a mature friendship but hasn’t quite figured out how. If Sandy feels compelled to change, so does Zuko. Have they compromised? Or have they learned more about what they want from life? Life is change, and even a teen musical can offer deeper lessons.

Grease was labeled problematic on initial release and is still considered problematic despite mainstream popularity. The movie has received multiple releases on VHS and DVD. Both the movie and soundtrack were re-released in 2018 to observe the 40th anniversary. A lifeless sequel was released in 1982 and a prequel series, Grease: Rise of the Pink Ladies, had a brief life on Paramount+. The original remains the Rydell High story we want. Newton-John didn’t pursue much more of a film career, but the post-Grease years saw the peak of her commercial popularity as a recording artist. Travolta soon appeared in the highly popular Urban Cowboy (1980) and Blow Out (1981); multiple career slumps and revivals led to his appearance as Edna Turnblad in another teen musical, Hairspray (2007). Stockard Channing has had a prosperous career in stage, film, and television, including seven seasons as first lady Abbey Bartlet in The West Wing. Jeff Conaway followed up Grease with a role in Taxi on NBC and had a recurring role in the s-f series Babylon 5 in the 1990s. Conaway later described childhood abuse and addictions that were exacerbated when he suffered a back injury filming the “Greased Lightning” scene in Grease; those addictions contributed to Conaway’s premature death at age 60. At the time I write this, Frankie Valli, who recorded the opening credits song, is still touring. As for the music, you either love it or you hate it, and if you love it, the songs are as infectious now as they were in 1978.

“Three decades later, American kids in the Reagan Era (The Neo-50s) would rebel in much the same way with the creation of punk rock. Just as the greasers sported leather jackets, engineer boots, crazy hairstyles, and other rebellious fashions, so did their descendants, the punks, have their rebellious fashion statements in tattoos, piercings, and occult symbols. And now, so does the hip-hop community.”

–Scott Miller, Sex, Drugs, Rock & Roll, and Musicals—

Teen comedies will always be a box office staple, but Grease didn’t instigate a new wave of teen musical comedies. The top-grossing “musicals” of the next two years were The Muppet Movie, Coal Miner’s Daughter, and The Blues Brothers. Grease remains something of an anomaly in contemporary cinema, a spectacle that remains lovable (with a 3.5 Letterboxd rating as of March 2025) despite being troubled and flamboyant. Elvis Presley died on August 16, 1977, while Grease was in production, the very day that Stockard Channing sang “Elvis, Elvis, let me be! Keep that pelvis far from me!” at the Pink Ladies’ pajama party. The song originally referenced Rebel Without a Cause actor Sal Mineo, but was changed in light of Mineo’s death in 1976. The music didn’t die, but the shadow of mortality forced us to pause. One of the blessings of cinema – and recorded music – is the ability to recall how young we once looked and how fabulous we sounded. Youth is such a brief experience that we shouldn’t be afraid of a little nostalgia, as long as we’re prepared to face the real world once the music stops.

Kids: Smoking only looks cool in the movies. In real life, you’ll smell bad and ruin your health.

Leave a reply to smellincoffee Cancel reply